‘They’ll shoot you, father,’ the woman’s voice said.

‘Yes.’

‘Are you afraid?’

‘Yes. Of course.’

A new voice spoke […] The voice said with contempt, ‘You believers are all the same. Christianity makes you cowards.’

‘Yes. Perhaps you are right. You see I am a bad priest and a bad man. To die in a state of mortal sin’—he gave an uneasy chuckle—‘it makes you think.’

‘There. It’s as I say. Believing in God makes cowards.’ The voice was triumphant, as if it had proved something.

‘So then?’ the priest said.

‘Better not to believe—and be a brave man.’

‘I see—yes. And of course, if one believed the Governor did not exist or the jefe, if we could pretend this prison was not a prison at all but a garden, how brave we could be then.’ […]

The woman said suddenly, ‘Think. We have a martyr here …’

The priest giggled: he couldn’t stop himself. He said, ‘I don’t think martyrs are like this.’ He became suddenly serious, remembering Maria’s words—it wouldn’t be a good thing to bring mockery on the Church. He said, ‘Martyrs are holy men. It is wrong to think that just because one dies … no. I tell you I am in a state of mortal sin. […] You have a name for me. Oh, I’ve heard you use it before now. I am a whiskey priest. I am here now because they found a bottle of brandy in my pocket.’ […]

The woman’s voice said, ‘A little drink, father … it’s not so important.’ He wondered why she was here—probably for having a holy picture in her house. She had the tiresome intense note of a pious woman. […] He had always been worried by the fate of pious women. As much as politicians, they fed on illusion. He was frightened for them: they came to death so often in a state of invincible complacency, full of uncharity. It was one’s duty, if one could, to rob them of their sentimental notions of what was good …

—Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory1

✠ ✠ ✠

Side B, then: traditional in premises and outlook, delicately balanced with respect to queer experience; a perfect blend of orthodoxy, innovation, and mysticism to serve as the sexual and philosophical avant-garde of the opening of this third millennium. Great. What about the times when it doesn’t bloody work?

To dispose of one less biting reason why it may not, I would like to point out that Side B isn’t and was never meant to be a universal panacæa. Admittedly I think that Side A is doctrinally wrong, and ex-gay efforts positively harmful. But there’s no reason why a given person couldn’t take the approach I’ve called Side Y, the sort taken by groups like Courage, and get a great deal out of it. I think the difference between a person for whom Side B, with its acceptance of much of gay culture and language, makes the most sense, and a Side Y person is going to be largely a matter of personal needs and tastes—not a matter of one method or the other being wrong. (Either might be used in a wrong way, of course, especially if it’s being used to bash others over the head; but that’s a different problem, and one characteristic of nearly every approach to every part of life.)

But that’s an accidental reason for not working. What about the times when the thing itself doesn’t work—you believe, you’re praying, you’re trying, you have the support of family and friends, you have a creative outlet … and somehow, it just isn’t enough?

I don’t think that Christians in this country take this possibility seriously enough. Catholics especially. Oh, we don’t believe in a health-and-wealth, Prayer-of-Jabez, power-of-positive-thinking Gospel According to St Joel Osteen. But we’re all too ready to take a view of both morality and vocation that I consider false and disastrous: because God grants us the graces to pursue these things, therefore sins, imperfections, and even sorrow and suffering are signs of some fundamental wrongness. But the truth is, happiness, sincere faith, and virtue don’t map to one another at all neatly on earth, especially since they can be hard to ascertain even in their own right. Man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart.

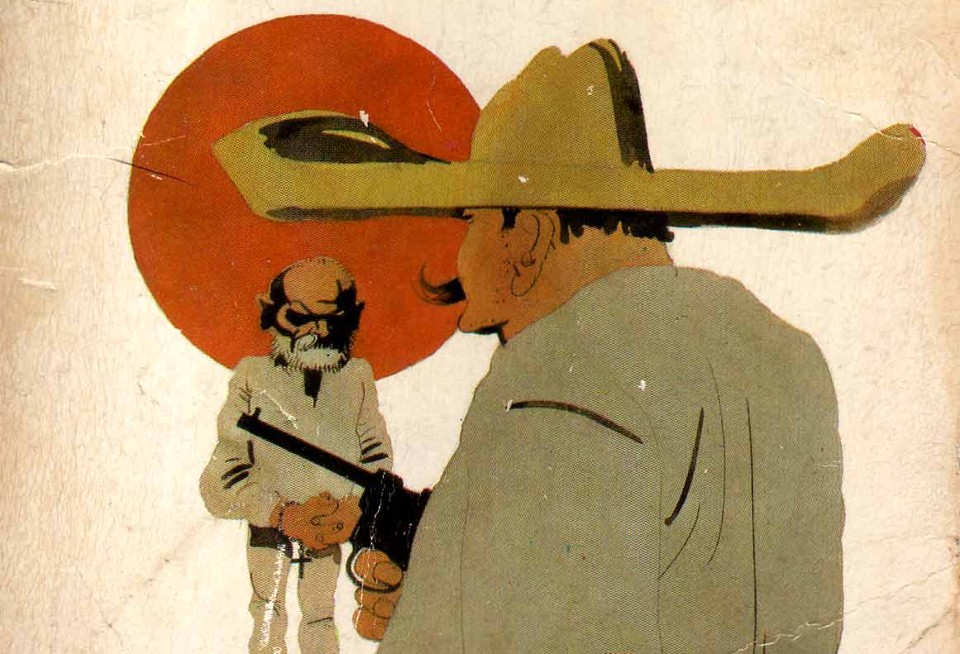

Screencap from 2015's adaptation of Silence.

Yet there have been Catholics who understood this very clearly. Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, Walker Percy, Shusaku Endo, and Flannery O’Connor made a habit of writing characters whose life is polluted with passionate, raging sins, and whose receptivity to grace is hidden—even, like O’Connor’s Francis Tarwater and Hazel Motes, hidden quite thoroughly from themselves, till the end. Something similar happened to Waugh’s Sebastian Flyte, the decadent and unhappy Catholic youth of Brideshead Revisited. Late in the novel, his sister Cordelia, who has seen him, mentally and physically ruined by alcohol, asking to be made a missionary by some monks in northern Africa (and naturally being refused), says:

‘There are usually a few odd hangers-on in a religious house, you know; people who can’t quite fit in either the world or the monastic rule. […] I’ve seen others like him, and I believe they are very near and dear to God. He’ll live on, half in, half out of, the community, a familiar figure pottering round with his broom and his bunch of keys. He’ll be a great favorite with the old fathers, and something of a joke to the novices. Everyone will know about his drinking; he’ll disappear for two or three days every month or so, and they’ll all nod and smile and say in their various accents, “Old Sebastian’s on the spree again,” and then he’ll come back dishevelled and shamefaced and be more devout for a day or two in the chapel. […] Then one morning, after one of his drinking bouts, he’ll be picked up at the gate dying, and show by a mere flicker of the eyelid that he is conscious when they give him the last sacraments. It’s not such a bad way of getting through one’s life.’

I thought of the youth with the teddy bear beneath the flowering chestnuts. ‘It’s not what one would have foretold,’ I said. ‘I suppose he doesn’t suffer?’

‘Oh, yes, I think he does. One can have no idea what the suffering may be, to be maimed as he is—no dignity, no power of will. No one is ever holy without suffering.’

‘Holy?’

‘Oh, yes, that’s what you’ve got to understand about Sebastian.’2

Is this what I’m foretelling of Side B people in general—or even simply of myself? No. I do, often, think it likely enough of myself (the bit about the messy life and, hopefully, the grace of a happy death—I am the last person who should have an opinion about my own holiness). But there’s no way of knowing the future, except by divine revelation, which is rarely addressed to our curiosity; or even, it seems, to our fears.

I bring it up, not as a prophecy or a prescription, but to make this point: for those who do stumble through life this way, God is just as madly in love with them as anybody else. Maybe more. That seems totally backwards to us—but then, the parables of the lost sheep and the prodigal say nothing else. Bad Christians are a sign that Christianity is doing its job, not that it’s failing through laxity.3 There should also be saints, and there shall always be saints. But it must be noted that saints come in very unlikely forms in the present, not just as a dramatic backdrop for a moving tale of conversion. St Mark Ji Tianxiang,4 who was barred from receiving Communion for thirty years due to a ruinous addiction to opium, rose miraculously to the occasion during China’s virulently anti-Western Boxer Rebellion, choosing to be martyred rather than renounce his faith and his Church.

Matthias Grunewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, 1516

After all, Christ did not come to make us disciplined, virtuous, kindly people. He came to draw us into His heart, to make us His bride, to give us His love and receive ours. This is why I’ve always disliked the pious Catholic commonplace that the purpose of life is to become a saint. The purpose of life is to be in union with God through love. Theologically, sure, those mean the same thing; but I’ll eat my hat if most people are prompted to think of union with God through love when they hear ‘Be a saint.’ What they’re far likelier to hear is ‘Do the familiar religious things the saints did: be chaste, go to Mass, pray the Rosary, give alms, &c.’ None of them bad things. But they’re all only instruments by which to love God: to the exact degree that they do not draw us closer to Him, every one of them is a stench in His face and a spike through His hand.

But even if all that’s true, about virtue being secondary and people with messy lives being just as likely to be saints as the righteous and so forth—is it really safe to say it? Is it really wise to assume that you can say this without people taking it the wrong way and using it as a license to do whatever they want? Well, it certainly isn’t safe; but neither is virtue. Impenitent virtue can create one of the loveliest, most complete, most durable armor-platings against the grace of God in existence. Satan fell through pride: we are not informed that any other flaw was found in him.

In any case, such worries seem to me to have gotten the order of the necessities exactly wrong. Virtue is not needed as a preliminary to love. Love is needed as a preliminary to virtue—and, more important, as both the means and the fact of unity with God the Father in Jesus Christ. If people do pursue His love, or are pursued by it, the rest will take care of itself; if not, then virtue really doesn’t matter.

And that, is that enough? Is that enough to sustain a person through the seasons of dryness and dark, the times when we wonder whether it might not be better to chuck the whole thing so as not to embarrass the Church, or because we so stingingly don’t deserve His love, or simply because we’re worn to exhaustion? I have no idea. Very probably not. What it does do, for me at least, is reassure me that it doesn’t have to be enough. This is in His hands, not mine. I’m not strong enough to ruin it. If nothing is enough, if I break, that’s actually okay. He can fix me, in His own time and manner. I’m His.

1Pp. 125-127. I first read this novel last year, and can hardly recommend it strongly enough.

2This is from Brideshead Revisited, but like a fool I’ve given my copy away, so I have no idea what pages. It’s reproduced pretty well in the BBC miniseries (and in fact, this is one of the rare instances where the filmed version is superior to the novel; certain parts of the book just aren’t the same without Diana Quick chewing the scenery).

3There is such a thing as laxity, of course. But the sort of person who complains about the laxity of others is not, as a rule, guilty of Christian perfection himself. And it is notable that of all the heresies the Church has had to contend with over the centuries, most have been excessively harsh, not over-soft.

4Pronounced, very roughly, Zhee Tyahn-shahng.

This is your best post ever.

ReplyDeleteI think you've made it.

I must concur. Thank you. Reminded me so much of reading that book too, years and years back.

ReplyDelete"Something resembling God dangled from the gibbet or went into odd attitudes before the bullets in a prison yard or contorted itself like a camel in the attitude of sex. He would sit in the confessional and hear the complicated dirty ingenuities which God’s image had thought out, and God’s image shook now, up and down the mule’s back, with the yellow teeth sticking out over the lower lip, and God’s image in its despairing acts of rebellion with Maria in the hut among the rats.” -Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory

Thanks for writing - I needed to read this today.

ReplyDelete