This post is about how going to a gay bar may have saved my Catholic faith.

+ + +

A good hustler knows that sex is important, but that contact with another human body is even more important -- it's something all people need at some times in their lives, for whatever reasons -- and it's hard to get enough of it.

-- Rick Whitaker,

Assuming the Position: A Memoir of Hustling, p. 42

+ + +

I've always been lousy at celibacy. I espouse the traditional Catholic view of gay sex because I think it's true, and I write about it because I'm the sort of person who's more or less incapable of shutting up, but I have no talent for it at all. It kind of makes me mad when people tell me I'm a good witness. The people who criticize me as a hypocrite, I can understand rather better than the people who idolize me.

I started having sex when I was thirteen. Well, sort of. I've written about this a little bit previously, though, for a multitude of reasons, not in great detail (

the previous post is here; be warned that it may be triggering for victims of trauma). Long, hideous story short, I was seduced and raped by a man about six years older than me. Nobody knew, and nothing further happened, for years; then, when I was sixteen, we started surreptitiously meeting up. The third time, we were caught.

Partly in response to all of this, and partly for other causes, I was way too closed off as an adolescent to actually, you know, relate to people in any way. I hardly had any friends until I was seventeen, when I started college.

"Friends? Ha! These are my only friends -- grown-up nerds like Gore Vidal, and even he's kissed more boys than I ever will."

"Girls, Lisa. Boys kiss girls."

During my closed-off period, it was fairly easy not to sex anybody. I mean, I didn't know anybody except other Christians, really, and I certainly didn't know anybody who was openly gay. Whether that counts as being good at celibacy I don't know; I'm inclined to think not. Probably it doesn't much matter.

At any rate, that situation didn't last. Since converting to Catholicism (accompanied by the usual fervor, which made things considerably easier for a while), I have experienced a strange mixture of things that have made even trying to be celibate a lot harder: loneliness and the wounds of loneliness, the incessant pressure of libido, resentment at the obligations of chastity (not very creditable I know, but there it is), trying to reclaim the personal power that was taken from me in the rapes, they all play a role. But one of the things I feel most strongly is the simple, unreflective hunger to be touched. Not touched in some metaphorical or emotional sense. Simply touched. There are definitely times when I've had sex, not because I was all that horny, but because I was starving to be held.

+ + +

I lived, for a while, as if repressing certain things was not only acceptable but somehow deeply appropriate. I had a mounting feeling that my life had become sufficiently corrupt that there was a kind of justice in my decision to disregard my feelings and my thoughts. I had done enough thinking, enough feeling, enough believing in the myths of progress and self-development and emotional work. The bets I had placed on myself -- as a writer, as an intellectual, as a loving and lovable human being -- were not paying off. It may have been vainglorious to have expected satisfaction in my twenties, but I was genuinely disheartened at the time.

-- Assuming the Position, p. 40

+ + +

Catholicism is, in my judgment, the only religion for the

demimondaine. The doctrine of justification by faith alone, in making good works to be solely the evidence of salvation, was meant as a comfort, but turns for the likes of me into despair; for, if the mark of true faith is an increase of righteousness, what then becomes of the sinner who goes on sinning? Who perhaps suffers many things of physicians, and spends all he has, and is nothing bettered? Even Luther and Cranmer had more sense than to do away with the confessional, and that, much though I owe to Calvinism, is more than can be said of Calvin.

It's often pointed out that the Catholic Church, far more than Protestant bodies, tends to contain a significant proportion of people whose practice of their faith is inattentive, superstitious, or nonexistent. Protestants would have us believe that this is a bad thing. I came in the end to see this as one of the strongest arguments in favor of the Church: namely, her power, in Msgr. Knox's phrase, to retain the affectionate loyalty of the erring; and her tendency to prove ineradicable from any soul that has once been stamped with her imprint. The only religion I can think of with a similar staying power is Judaism.

But it isn't only that Catholicism, in the sacrament of Confession, offers the assurance of individual forgiveness (something that statements of God's-love-for-sinners-in-general-and-therefore-for-oneself, if I may trust my experience, entirely fail to do*). It isn't even only that Catholicism allows that the soul is purified by love and not by intellectual belief alone.**

It is that Catholicism is intrinsically, in a way that few forms of Protestantism -- and very few other religions except Hinduism -- really are, a religion of the body. The Church's attitude to the body has often seemed ambivalent; it is full of unruly passions, which make the sort of people who are likely to become priests (in many religions) rather uncomfortable, and not least when they feel the force of those passions as much as the next man. But her belief about the body, that it is good -- that, in fact, God Himself took on a Body, and that that Body came from a body at once untouched and fruitful, and that Body infuses its own being into our bodies and souls by the bodily means of the Blessed Sacrament, so that spiritual coinherence itself coinheres with physical coinherence -- that belief has always been an unwavering touchstone of orthodoxy. Its persistence even in the face of the grimmest ascetical mood is what distinguishes the Catholic monk from the Gnostic perfectus or the Buddhist boddhisattva.

Behold My hands and My feet, that it is I myself: handle Me, and see;

for a spirit hath not flesh and bones, as ye see Me have.

It may seem strange to call that a comfort and a reassurance to someone who, like me, seems to be a

misplaced child of the Flytes. You would think it would make me more frightened and ashamed over my continual sins of the passions: the exalted significance of the body surely increases the gravity of such sins correspondingly. But comfort it is; partly because, by being a religion of the body, Catholicism is also a religion of beauty. Our own age may not be conspicuous for producing it, but Catholic art -- architecture, music, ritual, literature, poetry, painting -- is astonishing to me in its richness, its diversity, and its power to move the soul;

beauty ever ancient, ever new. And participation in that beauty is something that I can do, however imperfectly, even when my attempts at chastity are a complete shambles.

God's curious fondness, during His earthly life, for whores, barflies, and assorted rowdy nogoodniks is a reassurance too, of course. It is, or rather ought to be, impossible to feel quite comfortable with a spirituality that is thoroughly respectable. I cannot quite articulate why the two things -- the splendor of Catholic beauty, and her hold upon thoroughly disreputable people -- seem so firmly connected in my mind, aside from the fact that the one phenomenon is surely a reason for the other. It may be simply that both are bodily: the vividly material glory that makes a monstrance, and the vividly material passions that make a demimondaine.

+ + +

Some people, if not all of us, need to be fucked hard once in a while, both physically and figuratively. We sometimes need to prove to ourselves, somehow, that we are free, in some sense, from responsibility and from civilization. Most of us are embarrassed by this need, because it seems like an expression of weakness. Certainly I am weak -- to an extreme degree. I long to feel, if only for a moment, that whomever it is that is responsible for all the chaotic business of life, it's somebody other than me.

-- Assuming the Position, p. 154***

+ + +

The first time I ever went to a gay bar, the total experience -- the decision to go, being there, and the aftermath -- vividly exhibited the strange confluence of sensuality and spirituality I find in myself. I don't think it's intrinsically wrong to go to a gay bar: it depends on your motives for going; but, I wasn't going there to hand out tracts.

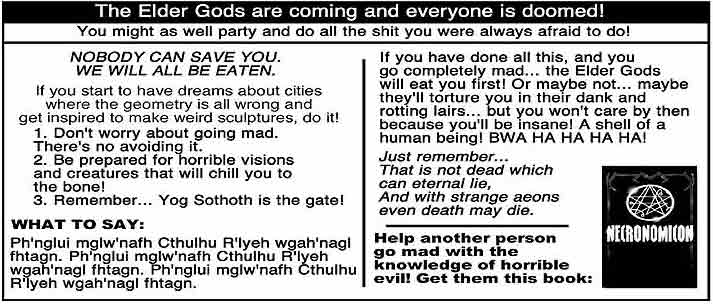

And honestly, if I had brought any tracts, they'd probably have looked like this.

The morning after -- but that phrase is so tangled in associations; it instantly calls to mind tangled sheets full of dubious fragrances, a series of gravely paradoxical or at best mysterious memories, and an intense desire that all nerves from the neck up cease relaying any light- and pain-related messages to the brain. But I digress. The morning after, I had thought, I would be crushed by shame, guilt, and fear. Or worse, I'd discover that I simply didn't care anymore -- that my conscience had just been suddenly pulled out of me, like a bad tooth.

Neither happened. That morning, a Sunday, I felt a huge, mysterious sense of gratitude. To God. And this was shocking, not just because it was the exact opposite of anything I had expected, but because, to date, I had almost never felt grateful for anything.

Why that is, I'm not sure (though I suspect it had a great deal to do with the duty of gratitude to God having been firmly impressed upon me from a young age: as C. S. Lewis pointed out somewhere or other, an obligation to feel can freeze feelings). What I was grateful for is hard to articulate, even to myself; it had partly to do with -- there's no point denying it -- having seen a lot of male beauty the previous night, and having been thrilled by it. That response had a great deal of lust in it, but I don't think it can be simply resolved into lust and so summarily dismissed. There was, too, the element of sheer relief in not fighting the theoretically good, experientially dismal and exhausting, fight, if only for a few hours.

There was, too, as a priest I spoke with about the matter later said to me, a new level of self-acceptance involved. The way I held myself, the way I talked, was completely different afterwards: there had always been a stiffness, a frigidity, in all my mannerisms before then, and now, I was just talking. And it wasn't about sex -- that night I hadn't had any. It was just ... you know, I still don't know what it just was. But somehow or other, that night, I made peace with being gay.

Part of that peace was a recognition that accepting myself wasn't incompatible with my beliefs. Most people will take this to mean that simply being gay isn't against Catholicism, and provided all our terms are properly defined, that's true, but it isn't what I'm talking about. It is, rather, that the truth of Catholic teaching and the sincerity of my belief in it, weren't dependent in the slightest upon my behavior. Somehow I'd never digested that fact before. Call it a relic of sola fide, maybe, but I'd been haunted by the fear that my works and my beliefs were tied together in such a way that if I didn't behave myself, I'd become intellectually dishonest. I discovered that night that that wasn't true at all; that the truth remained unblemished and solid whether I heeded it or not. That was a moment of deep liberation. I had feared before, subconsciously, that the truth was something my mind was generating. I knew now that it was real. And it's truth that I want the most.

I have been slowly making my way through The Life of Saint Teresa of Avila by Herself for several months now, and one thing about her writing has impressed itself on me strongly. She spends a lot of time talking about how wicked and foolish she was, and how astonishingly generous it was on God's part to shower favors upon her in the form of consolations, visions, and the like. At first I just thought of this as a sort of pious convention, because many of the saints talk about their own sinfulness, and the rest of us snigger and say, "Yeah, you were just terrible for not even entering a convent until you were fourteen, how could you live with yourself?"

Would you believe this jerk was never even martyred? What a lightweight.

But somehow or other -- I rather think she obtained this grace for me herself; the Carmelites have been looking after me for some time -- it occurred to me to wonder, What if she's just right?

For of course that alters the picture quite drastically. If, by some odd twist of fate, the great saint was not an idiot nor afflicted by a very morbid false modesty, and was, if only periodically, as wicked and silly as she professed to find herself, suddenly God's behavior toward me made a great deal more sense, and was a great deal more encouraging. I didn't and don't claim to thoroughly understand why going to a gay bar should have been followed by an overwhelming sense of love and intimacy with God, but what if He just chose to take an opportunity to show me that He loves me? And what if He did so, not because I deserved it, but because I needed it? Was that really totally incredible?

And the more I think about it, the more it makes sense. I was resorting more and more, as people of a religious temperament so chronically do, to what St. Paul calls the law in his letters, and what Victor Hugo depicted in the character of Javert: the habit, so engrained that it becomes a kind of belief, of putting one's confidence in one's own obedience -- justice without charity, virtue without grace. But that kind of obedience walls the heart against God still more thoroughly than against vice; and in breaking down the wall to admit a vice that was, at the same time, so bound up with a legitimate need, God too came into me.

And conversely, if Saint Teresa and the rest were right about themselves, and God used them gloriously anyway, perhaps I don't need to be quite so self-conscious. Or so egotistical, either.

*Far be it from me to suggest that a doctrine is true or false based on whether or not we find it practical or comfortable. I would suggest, however, that insofar as God made the human heart and understands how it works, we may expect Him to work with it rather than against it. On those grounds if on no others, we might consider the longstanding interpretation of such Scriptures as John 20.21-23 that is common to the Catholic and Orthodox Churches, and is the only recorded Christian view until the Protestant Reformation.

**Which is all the rejection of sola fide meant, if you read the canons of the Council of Trent. This is part of why Pope Benedict, former head of the CDF, was able to say to a synod of Lutheran bishops that the doctrine of sola fide as understood by Luther, i.e. faith inseparably united with love, was strictly compatible with Catholic orthodoxy. It is also presumably what St. James meant when he said in no uncertain terms that a man is justified by works and not by faith alone.

***I wouldn't like to leave the mistaken impression that, in quoting this, I am giving either this particular passage or the book as a whole my unqualified approval. What I am indicating is my recognition of the same impulse and feeling within myself, along with a hunch that it's a common craving among human beings.

.jpg)