It tickled my vanity to find, through a friend, my own name in (e-)print a few days ago.

Crisis Magazine published an article by Austin Ruse, titled "

The New Homophiles," reviewing the blossoming gay Catholic movement. I don't know anything about him except what I read in this article, which has already called forth responses

from Joshua Gonnerman and

Elizabeth Scalia.

It's very odd to read about yourself from an outsider's perspective. Joshua Gonnerman compares the article to an old-fashioned anthropologist's study, in which the customs of a people are described with some detail and some justice, but it doesn't seem to occur to the anthropologist to talk to the people he is studying, or to try using imaginative sympathy. That would be unscientific. Now, to do justice to Ruse, I don't know whether

Crisis allows for links to sources, though I'd be surprised if they didn't; but I gather from the aforementioned people, as well as Eve Tushnet and Chris Damian, that Ruse didn't actually speak

to any of us before deciding to speak

for us. He does admittedly quote us, but the quotes are not referenced or given any context, which leaves me unimpressed, at least with his method.*

I'd like to make several specific replies:

Tushnet is out, proud, celibate, and a Catholic faithful to the Magisterium. Tushnet says she is in love with the Church, its "beauty and sensual glamor." ... Tushnet is a true believer but she also speaks fondly in remembrance of her own lesbian experiences. All this is enough to give faithful Catholics vertigo.

Not to quibble, but a moment ago he just described her as a faithful Catholic, too. I assume, then, that by this he means faithful Catholics who also happen to be heterosexual; but Elizabeth Scalia (whom he has, for reasons best known to himself,** declared the "Momma Bear" of the New Homophiles) isn't a lesbian, and she specifically states in her own reply that it doesn't give her vertigo. What I think I sense here -- and one of the things that I tend to write about a lot here -- is a conflation of faithful Catholicism with social conservatism. The two gel quite nicely in many respects; but they are not the same thing, and shouldn't be treated as the same thing. Indeed, I think that the traditional alliance between conservatism and Catholicism (if we may call something traditional that has only been a social phenomenon for forty or fifty years) is going to become more of a hindrance than a help in the next decade, if it hasn't already.

One thing that social conservatism is unused to is, well, the LGBT movement. About the only category that conservatism has for openly gay people seems to be, roughly, Dan Savage: highly political, hostile to Christianity and especially the Catholic Church, and rather rude. And admittedly very unlike Eve Tushnet. Also, as it happens, unlike most gay people; we're really just people, except gay. Being gay -- that is, attracted to the same sex -- is our only distinguishing feature. Granted, that means we have a lot of shared experiences, but only in the same sense that heterosexuals have a lot of shared experiences.

She [Elizabeth Scalia] likely understands how difficult this new message is for the kind of Catholics who read her.

Here, I have to confess I lack due sympathy. And I don't mean that simply as a passive-aggressive "That's your problem"; I mean that the problem is legitimate, and I am really not good at sympathizing with it, which is a shortcoming of mine.

At the same time --

there are people killing themselves over this. My own outlook is of course jaundiced, not least because I have considered suicide. The woes of Catholics who are being asked to think outside of their accustomed boxes (without questioning Church teaching), are something that I have great difficulty even imagining, and whether I'm being fair or not, I am at any rate sick to death of the awkward feeling that some people get over a point of view, one just as orthodox as theirs, being given the lion's share of consideration in this discussion, by people who voice no interest in even understanding what it's like to deal with what we deal with on a daily basis.

Gay exceptionalism and charism are a regular theme for the New Homophiles. Gabriel Blanchard who calls himself a "gay, anarchist Christian" ... claims gay exceptionalism allows gays to have "lower tension in dealing with the opposite sex" and "a more intuitive understanding of certain forms of mysticism." Perhaps.

That I claim gay exceptionalism is news to me, chiefly because I don't know what that means. Exception to what? It comes in the context of a quote from Larry Kramer, a gay playwright who used that phrase; but I don't really understand what

he meant by it, either.

My own words cited here, from my post

Rethinking My Gay Celibacy, I would tend to stand by; though they did come before

an important turning point in my blog, and, again, are cited without the context that gives them their real meaning. (Not that I would wish to accuse Ruse of distorting me -- I don't think he has; just that what I say sounds sort of arbitrary in the truncated form in his article. It bears saying, though, that Chris Damian has complained of being misrepresented in this article, and, having read

the blog post from which Ruse quotes, it must be said that the point being made was that it doesn't truly matter whether Newman was what we'd call gay or not.)

The New Homophiles believe because of their gayness they have a unique ability to build close friendships, something that is lacking in our modern age.

This is also news to me. I do think we have a peculiar

tendency to form deep friendships, but that has more to do with the fact that, since we don't normally have an erotic outlet (to the extent that we are living in accord with the Church's teaching), we're likelier to pour a lot more of ourselves into friendships than our married friends tend to. There's quite a difference, though, between that sort of generalization and the thesis that we have an innate talent for forming profound friendships as a natural corollary of being gay. That

might also be true; I have no idea.

They are inspired by the works of St. Aelred of Rievault, a twelfth century Abbot and writer ... Aelred has been adopted by many gays, some of whom celebrate his feast day. Some claim he was gay though gays have a penchant for claiming historical figures as gay, often with little real evidence.

Admittedly, and that tendency annoys me too; though it could equally be said of Catholics that we love claiming people we like as being "so Catholic" in this or that way, sometimes in defiance of their actual profession (C. S. Lewis is a good example). In both cases, that's just the normal human instinct of liking it when someone seems to be on your team, so to speak; that isn't a specifically gay failing.

However, there is in fact concrete evidence that St. Aelred was gay (though of course, since the concept of a gay identity didn't then exist, he wouldn't have put it that way). Melinda Selmys mentions it in passing in her second comment on

this post on her blog. Some of us are indeed inspired by St. Aelred --

Spiritual Friendship, founded by the formidable Ron Belgau and Wesley Hill, is a splendid example -- but this has to do with his teaching precisely on friendship and its importance in a healthy spiritual life; it isn't necessarily linked to whether he was what we'd call gay or not. (I do celebrate his feast day, but that's because I'm Anglican Use and inclined to be pedantic, not because I'm gay.)

Their ideal is that you can draw close to someone of the same sex, love them intimately and intensely, yet never cross the line into sexual activity. ... But here they are playing with the hottest of fires. Perhaps this is possible for Christ and for saints like Newman but for others it could be a serious problem. This is why married men should avoid intimate friendships with women and why priests should also. This is why married men and priests who form intimate friendships with women often lose their way and ruin their vocations.

Well, again, it's news to me that we all have the same ideal, and that this is that ideal. Perhaps we had a group meeting to which I wasn't invited. Now, it so happens that I do think that the kinds of relationships he seems to be talking about here are possible -- I know more than one couple who are making precisely that experiment. But it's scarcely our defining trait. Some of us don't in fact think it wise; others of us are romantically as well as sexually celibate; some of us, like Melinda Selmys or Kyle Keating, are married.

But let's linger over the point a bit. To begin with, I have to agree with

this essay (by Melinda Selmys, it so happens) that this perspective on relationships is kind of foreign to me. Perhaps I'm secretly Canadian or something. I gather that this wasn't normal a generation or two ago, but among my generation, it is completely unremarkable to have close friends of both sexes; and not only are we in fact able to keep all the relevant bits in our pants, but the sexually charged atmosphere imagined to attend such friendships is, if I may trust my experience and that of my friends, quite simply not there.*** The idea that any genitals that can fit together, will, if they have only the time and something to hide behind, strikes me as paranoid and weird.

I have to wonder, too, whether this isn't a partly self-fulfilling prophecy. Name the devil, and he appears. You don't see the phrase often today, but Catholic moralists used to talk about the dangers of "morose delectation": that is, pleasure in thinking and speaking of the wickedness of others. I feel I see a great deal of this in a lot of conservative narratives about those godless liberals sexing each other with their sexy sex orgies all the time, and don't ever put yourself in a position where sex with someone is logically conceivable, because then you're just asking for it.**** One consequence of this -- it certainly has been for me -- is that it not only draws the mind to think about sex more than you would otherwise, but also strengthens the idea that sex is somehow irresistible by any but miraculous force. It is, in both senses of the word, demoralizing. By contrast, I've found that treating sex as simply part of the human experience enables me to realize that, yes, you can also

not have sex with someone, even if they're attractive; you can have morals and common sense and everything.

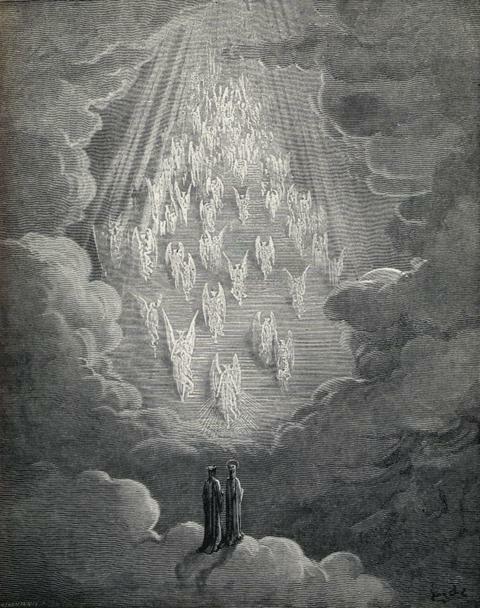

More importantly, I think this approach represents a wrong-headed approach to spirituality. It's so fear based. Take the concession Ruse makes about Christ and certain saints. Well, the Scriptures command us to imitate Christ, and one of the things that a canonization means is precisely that a person is worthy of imitation. If we

aren't supposed to imitate Christ and the saints, then who the hell can we imitate? Backing away from sins, and even from risks, is an obvious but wrong strategy. It is

pursuing God that matters, not avoiding sin as though non-sin were an end in itself. Pursuing God

always means taking some risks, and often means taking very big ones. And when we consider that we are talking precisely about building human relationships here, which are the context in which the love of God is normally expressed (as the dreadful parable of the Sheep and the Goats makes plain), I think we need to consider what we do to ourselves when we refuse to form relationships, too. After all, it is pride, not lust, that is the root of sin.

All that being said, I would add that I'm not unaware of the risks involved in this kind of thing. I attempted just this kind of relationship, and I did ruin it precisely with a selfish, stupid decision that I made because of lust. I regret that decision, the wound I inflicted on a man who was my dearest friend, and the consequent shattering of that relationship, every single day. I'm not saying there is no risk in that direction, or that the risk isn't important. What I am saying is that that is only

one dimension of the issue, and possibly not even the most important one.

Other experts at lay celibacy include every faithful Catholic who has never been married ...

Well, two things. First of all, this seems to me to be a massive oversimplification. Just because you're in a situation doesn't mean you understand it (a paradox I know only too well); let alone understanding anybody else's situation. And secondly, if he really means "every" here, then we New Homophiles count. We believe the Church's teaching, we're trying to live it out, and we're mostly unmarried.

There is also something narcissistic about this claim of gay-exceptionalism, that they are experiencing things no others have ever experienced, or that they have unique gifts given to them by dint of their sexual orientation.

Ouch. I mean, I don't think this is at all fair to most of us; but for me, that barbed arrow hit home. Anyone who has spent a little time with me thinks I'm a self-centered show-off. Anyone who has spent a little more time with me sees I actually do have a lot of self-esteem issues and the like. Anyone who has spent a little more time with me still, knows that they were right the first time. I write for other reasons too, but, yeah, this one I have to concede.

What they want more than anything is a development of doctrine.

I think that's fair. I tend to speak more about a difference in spiritual style, especially when it comes to evangelism. Certainly I believe that a lot of concepts that right now are held suspect or even categorically dismissed by most Catholics, such as sexual orientation, are actually useful and helpful, if only as mental tools to help us sort of the lived experience of LGBT people. I think, too, that the language we use -- not the essential

message, but the language -- has serious defects, not because of internal problems, but because of the divergence between what the Church means by certain words and what the culture at large means by them. And the thing is, when it comes to evangelism, it is we who need to go to the world. We don't get to just sit around waiting for them to recognize how right we are because they finally got around to reading a theological dictionary. It is we who must translate our language, not because Catholicism isn't right, but because it

is, and its rightness is being obscured by terminological discrepancies between the Church and the culture. When that is kind of the barrier we're dealing with, stubbornness over terms suggest pride and laziness rather that steadfastness about the truth. Those outside cannot be expected to just intuit what we mean, or to just see instinctively how important it is to investigate the Catholic faith.

After all, there are good men and women trying to be faithful but who reject the gay identity, and others who are trying to deal with the psychological genesis of unwanted same-sex attraction, a process the New Homophiles largely dismiss.

When

the head of the largest ex-gay organization in the world shuts it down and publicly apologizes for it, I feel fairly comfortable saying that the ex-gay movement is discredited. At least, discredited to the extent that association with it causes scandal; scandal being a worry I've heard about an awful lot in connection with being a Catholic who identifies as gay. I've written about

the theoretical problems that I at any rate have with ex-gay theory before, as well as of

the severe practical problems that have plagued the ex-gay movement since its inception, and the fact that

I don't see much point in it. This is not mere casual dismissiveness; these are grave objections to the philosophical groundwork of the ex-gay movement and its actual results in people's lives, borne not only of abstract analysis but of personal experience.

However, I think I tend to be on the more emphatically queer end of our little Catholic rainbow anyway (other than Aaron S-C of

An English Gay Catholic; I am perhaps the indigo to his ultraviolet).

En masse, I don't get the impression that most of us set as much store by gay identity as I tend to, or are as hostile to attempts at conversion therapy as I am. What does definitely seem true is that the subject really doesn't interest us. I am inclined to view it as a subtler, baptized form of precisely the same sex-worship that pervades American culture in general, at least insofar as it's aimed at making us suitable for Christian marriage. But, whether that's a fair or accurate evaluation or not, neither conversion therapy nor opposition to it is a main concern for any of us, as far as I can tell; neither is how people identify or describe themselves vis-a-vis sexuality. What we're concerned with is how to play the hand God has dealt us, not whether it's possible to swap some cards.

I must admit I started out annoyed.

Don't feel bad; I'm annoyed, too.

*Fortunately for me, I have never misrepresented anyone or forgotten anything or made any mistakes, ever.

**To be clear, I would be perfectly happy for her to be given this title: she's a thoughtful, rational, devout writer whose work I greatly enjoy, and she has written of us with great kindness and intelligence.

***Obviously, as a gay man whose friends are very largely straight men and some women (I don't run to stereotype in the female friends department, for whatever reason), my experience here is going to be shaped by that. But I'm taking into account my friendships with other gay and bisexual men, Christian and non-Christian, and also both my observations of my friends and the things they straight-up tell me.

****I have tried to think of some way of removing the double entendres from this sentence. There is no way.

.svg/1084px-Uganda_in_Africa_(-mini_map_-rivers).svg.png)