The approaching New Year has had me thinking about the artistic accomplishments of our century (and, indeed, millennium) to date, and I think we deserve due credit for having brought Jersey Shore and Rock of Love: Charm School into existence. Of course, for one of my tastes, "due credit" here would mean something along the lines of the reviews Sodom and Gomorrah got from Heaven, but perhaps the Lord is not so just as He once was.

Anyway, for those who care, here are my top ten most interesting artists of every sort from this century so far. This is most interesting, not necessarily best; I do in fact greatly like all the people I've listed here, but I've also left out a number of contemporary artists, such as Joss Whedon, whom I think talented and even brilliant, but who don't engage me as extensively or on as many levels as the following artists do. (For the musicians, I've tried to credit all the major band members I could find, but I couldn't find everyone, and even listing everyone I did find would be prohibitively long -- so, sorry to those who got shorted.) I've included a "See also" list for other artists that I find interesting for some of the same reasons, though they aren't necessarily that stylistically similar to the entry listed.

1. Sufjan Stevens

For I could not have shaken the touch of your breath on my arm

For it has stayed in me as an epithet

I am sorry the worst has arrived

For I'm on the floor in the room where we made it our last touch of the night

-- "I Walked," The Age of Adz

Art: Music

Style: Cryptic, genre-defying, romantic, mystical

Notable work: Seven Swans, Illinoise, Silver and Gold, The Age of Adz

Why he fascinates me: My first exposure to Sufjan Stevens was in the early years of college, via the album Illinoise, and it was a mind-altering experience. The range and inventiveness of Sufjan Stevens' work was like nothing I'd heard before. He shifts effortlessly between subdued folk stylings, baroque electronica, blendings of high orchestra with experimental rock, playing by no rules except the ones that dictate the interior logic of the work. Some musicians go through fewer musical ideas in a career than he can span in a single album -- and he's phenomenally prolific, having released eleven albums (some of them quite lengthy) since his 2000 debut A Sun Came. His lyrics are something else: I've rarely heard such poetry in popular music outside of Leonard Cohen. His religious pieces mix freely and naturally with the rest of his work, much of which is about the good and bad aspects of family, or found and lost love; and none of it is constricted by the saccharine, conventional tactics of much pop music and most Christian music. It's a crime he and his band haven't won a Grammy.

Recommended sample: "Casimir Pulaski Day" and "Get Real Get Right." The two songs, taken together, give you a fairly broad sampling of his style: the one is from Illinoise, one of the earlier albums, and is more or less pure folk; the other, from his recent album The Age of Adz, and exhibits his frequently weird and sci-fi-like lyrics, together with his willingness to combine classical and electronic elements.

2. David Wong

"I'm not crazy," I said, crazily, to my court-appointed therapist.

-- This Book Is Full of Spiders

Art: Literature

Style: Morbid, unreliable-narrator-ridden, full of pop- and net-culture riffs, intricately plotted

Notable work: John Dies At the End, This Book Is Full of Spiders

Why he fascinates me: David Wong (real name Jason Pargin) is a cunning author. The influence of movies and video games on his work is clear, but these are not cut-and-paste jobs like the meme-quilts one sometimes finds passed off as humor. His plots, and the philosophical problems (notably of identity, free will, epistemology, and social dynamics) that they explore or suggest, are powerfully constructed, while at the same time being veiled behind a layer of apparent shallow and irreverent douchebaggery. The dark, insane humor of the books and their easy prose make them extremely readable, and the universe Wong has constructed is mechanically fascinating, while sucking the reader by degrees into profound ethical analysis. Though by no means a manifestly religious writer, the books do turn upon some profoundly important questions and motifs characteristic of Christianity, Spiders particularly.

Recommended sample: John Dies At the End. There is a (grossly truncated, but still pretty good) film version, available on Netflix (or it was the last time I checked), summoned into existence by Don Coscarelli, creator of the cult classic Phantasm series and Bubba Ho-Tep, and featuring Paul Giamatti. The nice thing about the film is that it keeps the second-biggest twist of the book's plot, while leaving out the first, so that if you choose to whet your appetite for the book with the movie (as I did) you can still come to the book fresh.

See also: Wayne Gladstone, Tim Powers

3. Welcome to Night Vale (Joseph Fink and Jeffrey Cranor)

A friendly desert community where the sun is hot, the moon is beautiful,

and mysterious lights pass overhead while we all pretend to sleep.

-- "Pilot," Welcome to Night Vale (Episode 1)

Art: Radio (podcast)

Style: Lovecraftian, darkly humorous, absurd

Notable work: Every gorram episode; but, among the earlier episodes, 6, 10, and 19 are some favorites of mine

Why they fascinate me: This is the podcast that made me willing to be interested in podcasts, which I had hitherto ignored utterly. The show is basically NPR for a town where all of the X-Files are true, and in fact common knowledge -- at least, that's how it starts; as it proceeds, it gathers a plot and a collection of genuinely compelling, complex, sympathetic character arcs to itself, and makes a number of surprising moves. Like the previous entry, it is largely black comedy; like the next, and to some extent like Lewis Carroll, it plays a great number of delightful word games; but the feel of the place is all its own, and I've never met its equal. It makes a wonderful use of the limitations of its sound-only medium, creating characters and achieving imaginative effects that could only be depicted with great difficulty and expense via CGI, or in some cases (such as the character of the Faceless Old Woman Who Secretly Lives In Your Home) couldn't be produced at all. The podcast itself can be found at Commonplace Books, along with a number of other cool things that are really hot.

Recommended sample: This YouTube clip of the first half of "The Drawbridge," Episode 6. This contains some nice Night Vale fan art, of which there is a great deal, and also happens to have French subtitles.

See also: The Last Lovecraft: Relic of Cthulhu (film), Todd and the Book of Pure Evil (TV series)

4. Randall Munroe

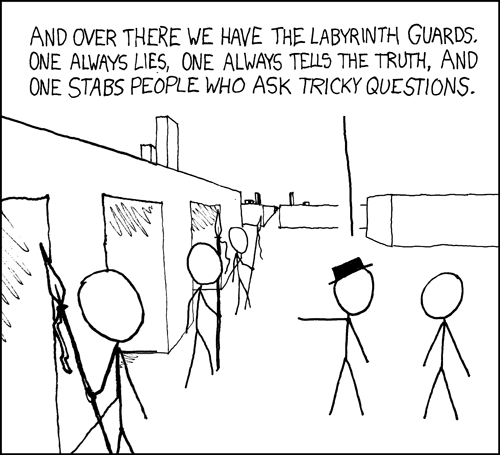

And the whole setup is just a trap to capture escaping logicians. None of the doors actually lead out.

-- Labyrinth Puzzle (xkcd 246)

Art: Webcomics (artist and writer)

Style: Visually sparing (for the most part) but remarkably expansive at times; verbally quick, ironical, and lighthearted

Why he fascinates me: There seems to be a curiously large number of physicists-turned-comics-artists (Bill Amend, the author of Foxtrot, is another), but Randall Munroe is far and away my favorite. The simple appearance of his art and even of many of his jokes belies a magnificent wit and creativity. Though a lot of his material is written for fellow math and science nerds, even most of that is comprehensible to a layman like myself, and a lot of his humor is pure, delightful silliness, word games, or appeals to universal human experience.

Recommended sample: Ah, don't make me choose! But this, this, this, and this are a very few of my favorite strips.

See also: Jeph Jacques (Questionable Content)

5. mewithoutYou (Aaron Weiss and others -- highly mutable membership)

Like an anchor-ever-dropped, seasick-yet-still docked

Captain spotted napping with his first mate at the wheel

Floating forgetfully along, there's no need to be strong

We keep our confessions long and when we pray we keep it short

-- "Messes of Men," Brother Sister

Art: Music

Style: Raw, dissonant, heavily textured, symbolic, God-haunted

Notable work: Ten Stories, Brother Sister

Why they fascinate me: I was raised, not exclusively, but very largely on Christian music, and an awful lot of it sucked. mewithoutYou don't consider themselves a Christian band per se (Weiss' parents, a Jew and a former Episcopalian, became Sufi Moslems when they married, it seems, so I have no idea what he or the other past and present bandmates consider themselves), but they deal with a lot of spiritual themes, most if not all of which are familiar and hospitable enough to a Christian; and, rarity of rarities, they do so with a deep, painful honesty and anguish that most professedly Christian artists are, to be blunt, too squeamish to employ. The fact that they're able to make their music, which is extremely avant-garde, sound good, is an accomplishment in itself -- it's one of those things that is easy to do at all but hard to do well, like free verse, and I find their mastery (particularly the diversity of the instruments they use) compelling. In addition to being profound, I find their lyrics unusually communicative despite their cryptic, allusive nature. I think and hope that mewithoutYou, along with Sufjan Stevens above, represent a new trend in Christian and Christian-influenced art, of simple artistic honesty and of viewing all human experience -- nice or not -- as proper material for the artist.

Recommended sample: "Fox's Dream of the Log Flume" from Ten Stories. The striking confluence of themes, the weird lyrics, and the unpolished, avant-garde sound are all highly characteristic.

6. Stephan Lacant

[After being punched by homophobic colleague] Is that the best you can do? Pussy!

Art: Film (director, writer)

Style: Meditative, with powerful moments of graphicness and/or brutality

Notable work: Freier Fall (English title "Free Fall")

Why he fascinates me: I ran across this film on Netflix, and was extremely impressed by it. So far as I can tell, this is Lacant's first professionally produced film; it's sort of a German response to Brokeback Mountain (response, not rip-off). The initiation of the story isn't quite as strong as it could be, but the rest is, in my judgment, perfect. The development of each of the central characters is perfect at every step, working out flaws to their logical conclusions in a manner reminiscent of Aristotle's advice in the Poetics. Lacant makes an excellent use of silence, something a lot of filmmakers, especially in America, seem to be rather afraid of (remember how Cast Away stood so alone in that way?); and, though there are rewarding moments and heartbreaking ones, the film never once slides into mere sentimental showmanship. I'm excited to see what else Lacant does, and I hope we don't have to wait too long.

Recommended sample: Freier Fall. Last time I checked, it was still available on Netflix instant, and is subtitled, not dubbed, thankfully. (Warning, it's a bit graphic -- there are a few, short scenes that pretty much amount to soft porn.)

See also: Weekend (film, dir. Andrew Haigh), In the Name Of (film, Polish title W Imie, dir. Malgorzata Szumowska)

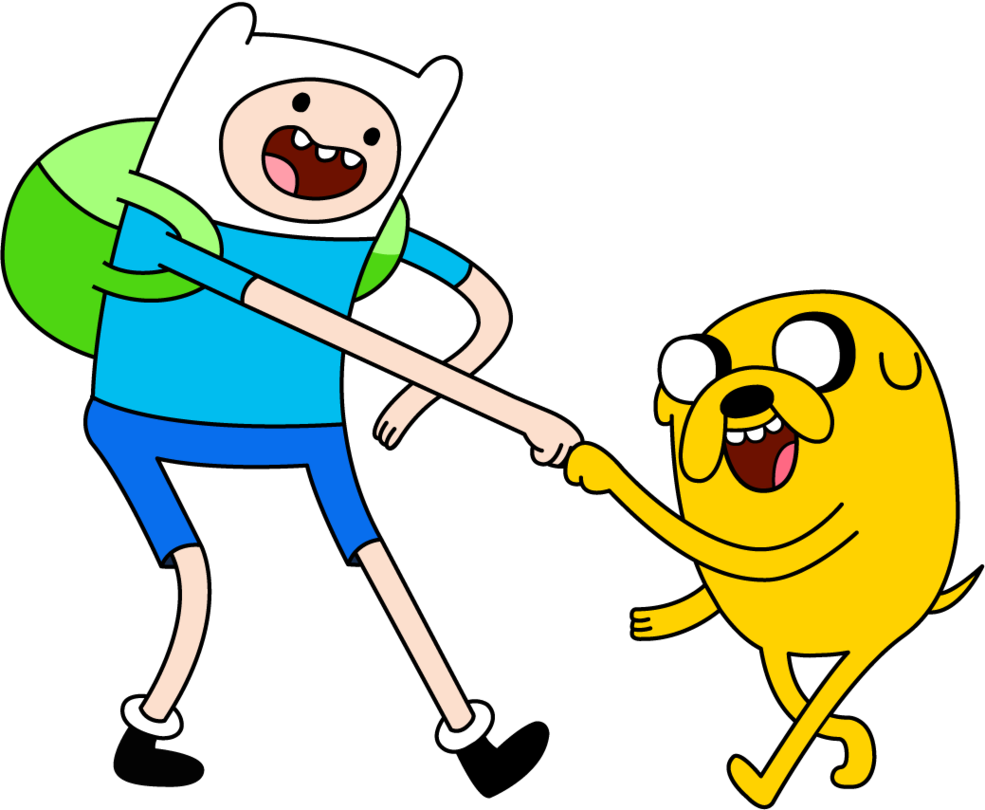

7. Pendleton Ward

"If you want the Hero's Enchiridion, slay this unaligned ant!"

"NEVEERRR!"

-- "The Enchiridion!," Adventure Time (Season One, Episode 5)

Art: Film (writer, animator)

Style: Innocent, mercurial, re-inventive

Notable work: Adventure Time

Why he fascinates me: Pendleton Ward is a good representative of a new trend in popular art, which was arguably started by the Homestar Runner website, of renewed innocence. Innocence is not generally spoken of as a good quality in art -- it tends to be equated with naivete, and relegated to children's books and cartoons, and it's certainly true that Adventure Time (and the other examples I've given below) are suitable for children. But the wit and creativity of these pieces far outstrips anything that most young children would notice or care about, and there are elements of each that are clearly designed for the pleasure of adults. This trend seems to me to represent a deeply healthy, and perhaps unconscious, assertion that innocence and maturity can be combined, as opposed to the cynical view that maturity and corruption tend to correlate. But, in addition to that, Adventure Time is just a great show: delightfully animated, funny, energetic, and imaginative.

Recommended sample: "Trouble In Lumpy Space," the second episode of the first season. This extensively features Lumpy Space Princess, one of my favorite supporting characters in this, or indeed any, series, who is voiced by Ward himself.

See also: Lauren Faust (My Little Pony reboot), Hayao Miyazaki, The Brothers Chaps (Homestar Runner)

8. Haint Blue (Mike Cohn, Dave Sheir, Mike Wolfe, Abby Becker, Nellie Sorenson, Ian Finch, Alex White)

As it was in the beginning, so shall we all turn to dust

But first I'm gonna kill you, son

-- "Father Abraham," Company of Ghosts

Art: Music

Style: Reinvented folk, with anticorportaist and sacrilegious themes

Notable work: Company of Ghosts

Why they fascinate me: I have written about Haint Blue before, quite recently in fact (and it so happens that they're playing here in Baltimore on the 2nd at the Ottobar). In addition to their great musical talent, Mike Cohn's lyrics are compelling in their explicit dealings with both the rejection of childhood religion and the inevitable familial consequences of that rejection, among other themes. There's something in it that reminds me of Flannery O'Connor, actually, though obviously not sharing her final conclusion: something of the same pungency and spiritual shock. In their own, very different, way, they're quite as profound as Sufjan Stevens or mewithoutYou on the other "side," and they're a talented bunch.

Recommended sample: "Father Abraham." The song "Untitled" at the beginning of the album is another stunner.

9. Lady Gaga

I'm just a holy fool, oh baby he's so cruel

But I'm still in love with Judas, baby

-- "Judas," Born This Way

Art: Music

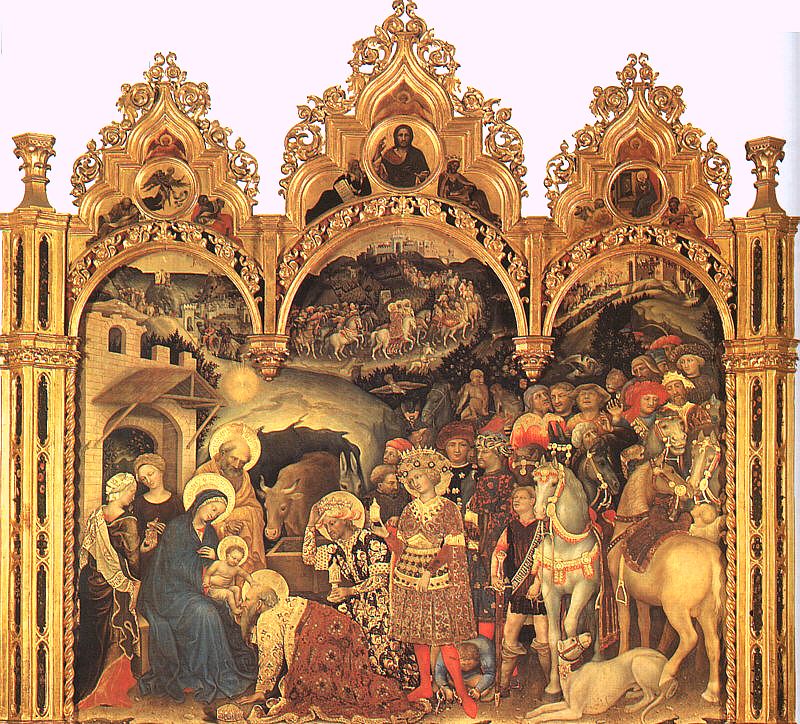

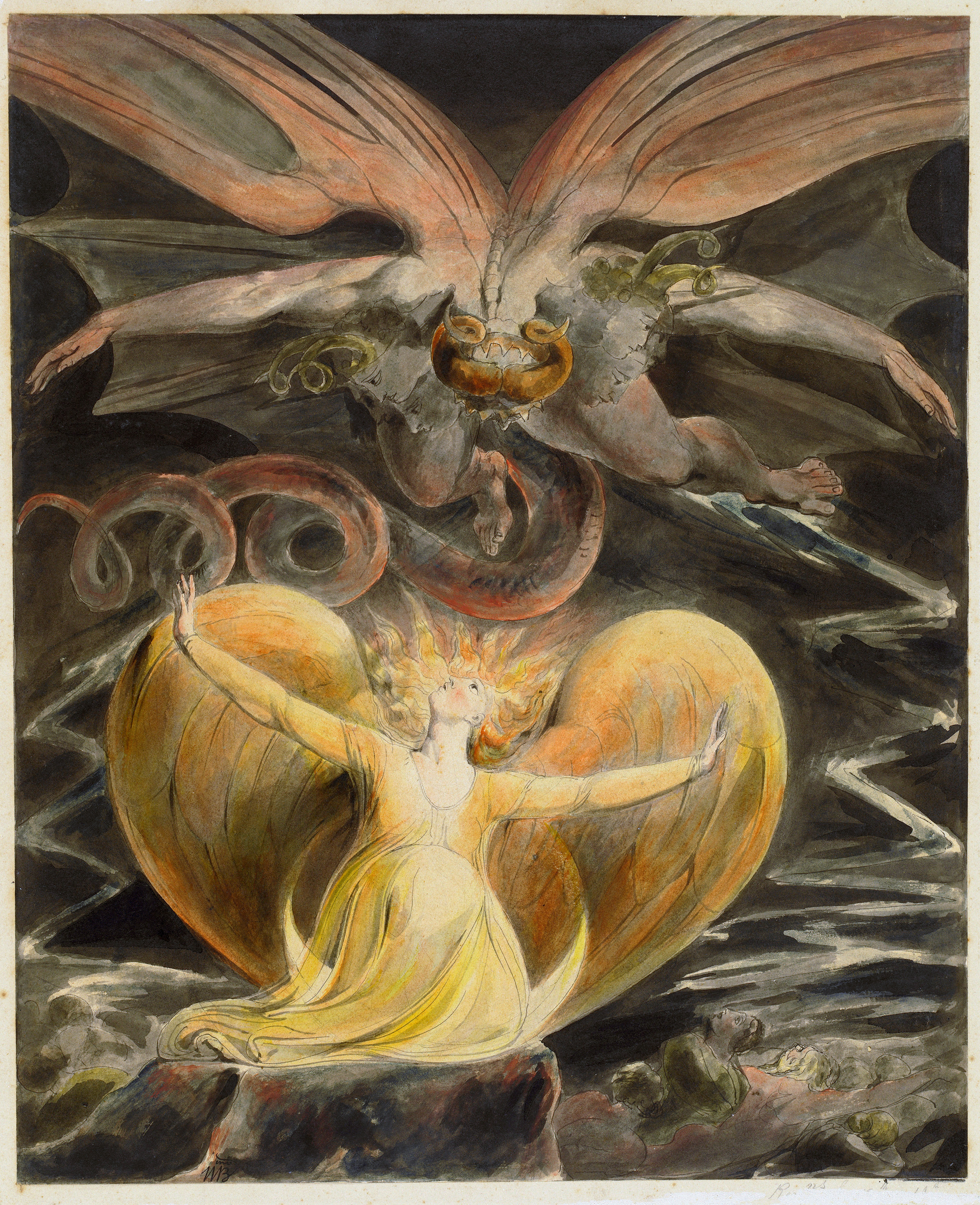

Style: Over-the-top, highly sexed, ridden with Catholic symbolism

Notable work: The Fame Monster, Born This Way, ARTPOP

Why she fascinates me: Lady Gaga (nee Stefani Germanotta) was what I had kind of hoped Madonna would be: musically outstanding, incredibly lavish, and catchy as hell. I think she's underrated as a musician -- the rather cold reception of ARTPOP this year was, to my mind, an injustice to it, and particularly to the way she seamlessly blended dubstep influences into her earlier work. The thing that's really arresting for me, though, is her music videos, and especially their extensive use of Catholic imagery. To take one example, when "Judas" came out, the Catholic League complained about the music video (apparently without watching it, since the only people who could be said to be disrespectfully portrayed in it are Judas and the singer herself; not to mention the fact that the whole Judas motif is metaphorical anyway). I loved it, and found its allusions to Catholic artwork and religious iconography fascinating, and even, maybe, suggestive of a religious side to Lady Gaga that coexists with her extremely sexual stage persona -- it not being mine to say how true-to-life that stage persona is. I don't often feel I see musicians construct music videos that gel as finely with the songs they pair with as hers, which are more like genuinely multimedia affairs, instead of just "Here's a song. Oh, and here's a video." The complexity and ambiguity of her image, and its unclear relationship to her as a person offstage, seems to me to be itself an icon of much American pop culture and its relationship to the American people as we actually are. It'll be interesting to see whether that stays true.

Recommended sample: Again, hard to choose, and in any case most of you have heard a lot of her songs already. I think I'd go with "Aura" and "Monster," since those two (though in my opinion excellent specimens of her work) were never singles; I'd also recommend "Judas," partly for itself and partly for the visual splendor of the music video.

10. Christopher Nolan

I have to believe in a world outside my own mind. I have to believe

my actions still have meaning, even if I can't remember them.

-- Memento

Art: Film (director, writer)

Style: Dark, cerebral, philosophic, apt to jump around in time and space

Notable work: The Dark Knight, Memento, Inception

Why he fascinates me: I didn't really appreciate Nolan's work at first, in part because I always had a hard time remembering the names of directors. But, partly thanks to this article by Wayne Gladstone (whom we encountered in the notes to Wong's entry above), I suddenly began to piece together his cinematic career and its striking, individual quality. Stanley Kubrick could be as dark and brainy as Nolan, and a good deal weirder, but Kubrick seemed more interested in exploring the fringes of perception and thought, whereas Nolan seems almost to be translating central questions of epistemology into cinematic form -- though without being, for lack of a better word, preachy about it. The fact that he's able to film energetic, coherent narratives while darting from place to place and even time to time certainly establishes him as a consummate storyteller, Memento being the extreme example. Nothing against Martin Scorsese, but I kind of wish they'd handed the upcoming film version of Silence to him instead. I still haven't seen Interstellar, but I plan to.

Recommended sample: Inception, in addition to being an excellent movie, is probably the least grueling to watch -- grit being definitely one of Nolan's hallmarks.

See also: Quentin Tarantino, Kurt Sutter (creator of Sons of Anarchy), Baz Luhrman

Honorable and grossly-abbreviated mentions include After Hours (by Michael Swaim, Katie Willert, Soren Bowie, and Dan O'Brien), Rick Whitaker (Assuming the Position), the Wright-Pegg-Frost-Stevenson constellation (Spaced, Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz) and The Wrong Mans (by James Corden and Matthew Baynton). But I'm honestly a little surprised I made it through ten, so I'll cut it off here.

And, Happy New Year, especially to my top ten countries of readers! Thus, to my readership here in the States, up in Canada, across the pond in the UK, and down under in Australia; Z Novym Rokom to my Ukrainian readers (sorry, the computer I'm using doesn't have settings for other alphabets, or none I know how to use); Bonne Annee to my French-speaking readers; Szczesliwego Nowego Roku to my Polish fans; Glukliches Neues Jar to my German readership; Tahun Baru Gembira, Malaysian readers; and S Novym Godom to my readers in Russia. I hope your 2015 is outstanding, everybody, whenever you are.

.jpg)

.jpg)