My current series has been getting difficult to write lately (turns out struggling with faith is hard -- who knew?), so I'm taking a bit of a breather before I continue. Since today is Michælmas -- the Feast of Saints Michæl, Gabriel, and Raphæl the Archangels, and therefore of one of my special patrons -- it seems like a fitting day to take off, and I have done.

Michælmas is rather special to me as an Anglican Use Catholic. Our calendar preserves a lot of elements that are no longer observed in the normal Roman Rite, or whose importance has been reduced; the Octave of Pentecost is one (Pentecost observed over a span of eight days instead of one, like Easter and Christmas), and this is another. The veneration of the angels doesn't seem to hold the same stature in Catholic spirituality that it once did, unless my observation is incomplete. I find the whole doctrine of angels fascinating, especially as a fan of both magical realism and sci-fi; the Second Choir seem especially apt to that kind of exploration (and C. S. Lewis essentially did just that in much of the Cosmic Trilogy): the Dominations who direct the Virtues, the Virtues who govern natural forces and bodies, and the Powers who observe and direct human history, all seem to me eminently suited to be understood, in terms of fiction, along the lines of transdimensional intelligences whose functions literally structure and energize the universe. Tell me that's not pretty cool.

They always seem to want to give him kinda girly hair for some reason, but still.

Michael the Archangel, Guido Reni, 1636.

+ + +

II.

I think that, among American believers today, probably the most aggravating part of being gay is the way people turn you into a mascot.

Honestly this just encourages me. A clear grasp of fundamentals is the first step in not being a raving dumbass, after all.

Some -- many -- don't, of course. But whether you're being rebuked for other people's sins, or fêted for imagined victory over sins that still plague you, all based exclusively on whose "side" you are perceived to be on, it's deeply disrespectful. It treats you as the symbol of a people-group, usually in such a way as to (seemingly) absolve the person thus using you of having to actually get to know gay people, or Catholics, or gay Catholics, or Side B folks, in general. And, not infrequently, they show no interest in actually getting to know you in particular either. A lot of Catholics talk about the need not to reduce people to a label but rather to respect their holistic human identity, but frankly, I feel far more dehumanized by being treated as an example than I do by a guy who isn't interested in anything but my body -- and whom I can't really judge in the first place.

It makes for a lot of mixed signals, too. I particularly feel this way dealing with Catholic groups and people who are opposed, even hostile, to coming out of the closet -- yet will say in practically the same breath that the Church needs people to model chastity. So, just don't let on that your example could be in some way relevant to the people you're (apparently) a role model for, is the desideratum?

You hide your face magnificently! Everyone will relate to the anonymous and therefore unverifiable

life you're "sharing"! Next up: How to speak so quietly that people give up trying to talk with you!

+ + +

III.

A huge mass of books were available at my parish yesterday after the liturgy -- from where, I don't know -- but they formed some rather intriguing combinations. Along with such excellent Anglo-Catholic works as Creed or Chaos? and The Mind of the Maker (both by the brilliant Dorothy Sayers) and a large quantity of prayer books, were the comparatively thematically irrelevant, like Cyrano de Bergerac, and the quite unexpected, like The Vampire Armand. It makes me wonder what people going through my library would think, seeing everything from The Prophet to Assuming the Position on one shelf. If, as some postmodern authors say, books talk among themselves, I imagine that library was a novel experience for them all.

+ + +

IV.

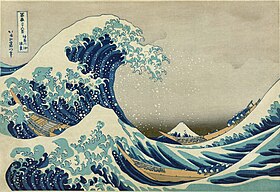

Another reason the problem of suffering has got me more worn out than usual is that, last month, I read the justly famous novel Silence, by the Japanese Catholic author Shūsaku Endō. It's a magnificent, and at the same time a brutal, read. In barely fictionalized terms (based on and incorporating several historical figures), it depicts the persecution of the Church in Japan in the seventeenth century.

Kanagawa-oki nami-ura ("The Great Wave off Kanagawa"), part of the Thirty-Six

Views of Mount Fuji woodblock series, by Katsushika Hokusai, composed around 1830.

Christianity had been well-received at first, when St Francis Xavier visited the island nation in the latter half of the sixteenth century; indeed, he said that they were some of the finest people he had yet encountered, both in general and in terms of receptivity to the gospel. But imperialistic rumblings from the European Catholic powers, combined with increasing nationalism (and corresponding centralizing and xenophobic trends) under the Tokugawa shogunate, led the Japanese government to outlaw the faith, and to go on to carry out one of the most cruel and effective campaigns of religious extermination the Church has ever seen in her history. Two things that made it so effective were that it focused upon priests more than ordinary believers, knowing them to be the linchpin of the operation, and that it directed its efforts less toward martyrong people -- they found out early on that that was received as a glorious victory by the Catholics -- than towards making them apostatize, breaking the spirit of the infant Japanese Church and tearing up the roots it had formed.

You can't do that to Christianity of course; and, I would argue, you can't do that to the Japanese, either. Deprived of priests for more than two hundred years, forced to trample upon icons of Christ and the Virgin to absolve themselves of suspicion, the Japanese Catholics maintained the faith in secret: passing on the teachings, reciting the prayers, and living in hope for the day when, they said, the fathers would return. And return they did: in the middle of the nineteenth century, when Japan was reopened and Christianity was legalized, the kakure Kirishitan or "hidden Christians" emerged, thirty thousand of them, with their prayers preserving fragments of the Latin and Portuguese the first missionaries had taught them, still clutching scraps of cassocks and rosaries kept safe from the authorities for generations; nearly all were received once again into the heart of the Catholic Church. It calls to mind Tolkien's stirring words from the tale of Eärendil in The Silmarillion: "Hail, the looked for that cometh at unawares, the longed for that cometh beyond hope!"

Mosaic of the Virgin and Child, in the Church of the

Annunciation in Nazareth, donated by Japanese Catholics.

It's one of the most beautiful and astonishing stories in history, in my opinion. But Endō's novel is about the tragic beginning, rather than the eucatastrophic ending. It details the story of one priest, Sebastian Rodrigues, who has secretly entered Japan to sustain the Christians, and is struggling with his incomprehension in the face of God's silence, His inaction, while His children are suffering so mercilessly. Part of this is expressed in one of the "hard sayings" that is easy to miss: Jesus' words to Judas before the betrayal, "What you do, do quickly." That He should urge Judas on in this, one of the worst sins in history, is an intolerable thought to Father Rodrigues and ... ah, you have to read it.

Martin Scorsese has announced his intention to adapt Silence for the silver screen. If they fuck this up, I may just spontaneously combust, out of pure artistic wrath, right there in the theater.

+ + +

V.

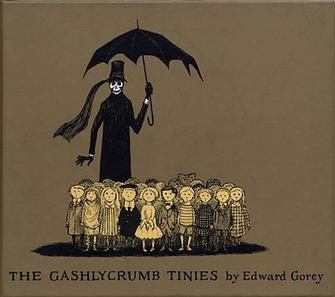

I still haven't come up with a good reward for my patrons -- thank you all, by the way, I truly appreciate your generosity to me -- and I only have till the first before I start feeling bad. (Your cards were not charged for August, owing to a mistake I'd made in the set-up, which is why there was no reward this month.) I wish I could draw like Edward Gorey and make fun little gay Catholic anarchist pictures of things, in the style of The Gashlycrumb Tinies, but my odds of managing to do that between today and Wednesday seem, eh, slim. Well. I'll think of something.

A is for AMY who fell down the stairs

B is for BASIL assaulted by bears

C is for CLARA who wasted away

D is for DESMOND thrown out of a sleigh ...

.jpg)