By necessity practical and by philosophy stern, these folks were not beautiful in their sins. Erring as all mortals must, they were forced by their rigid code to seek concealment above all else; so that they came to use less and less taste in what they concealed. Only the silent, sleepy, staring houses in the back-woods can tell all that has lain hidden since the early days, and they are not communicative, being loath to shake off the drowsiness which helps them forget. Sometimes one feels that it would be merciful to tear down these houses, for they must often dream.

—H. P. Lovecraft, The Picture in the House

✠ ✠ ✠

I am a fan as well as an author of horror, and I’m correspondingly picky about what things give me that delicious, skin-crawling sensation that we seek from horror. Jump scares, carnivorous aliens, and common murderers don’t do much for me: anybody can write that. What I for one want out of a horror movie is a sense that the range of possible experience has been enlarged; it isn’t mere nervous shock, but imaginative enrichment in the realm of the terrible, that makes really good horror. For those who share that taste, I offer thirteen suggestions for an eerie Halloween this year.

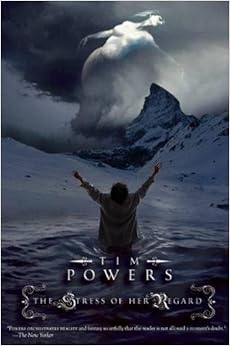

13. The Stress of Her Regard, written by Tim Powers. This brilliant reinvention of the vampire novel which blends its traditional undead antagonists with the Gorgons and the Muses, is a wonderfully persuasive piece of writing. I prefer the romantic yet depraved monsters of Anne Rice (or even Bram Stoker) to the recent flush of merely sentimental vampires that people like Stephenie Meyer have given us, but I prefer Powers’ bizarre, inhuman creations to either. The novel drags in places, but it’s a lavishly constructed world and the characters are beautifully painted.

12. Pan’s Labyrinth, directed by Guillermo del Toro. With this film and the book beneath, I was half-tempted not to count them, since they’re more dark fantasy than horror proper. Then I decided that was stupid because nobody cares, and besides, I recommend them both. Pan’s Labyrinth is a wonderful modern fairy-tale, and, like many good fairy-tales, also contains one of the most terrifying monsters I’ve ever seen, the Pale Man. With del Toro’s trademark effects and perfect sensibility for Faërie, this is not a film to miss if you have the slightest taste for fantasy, foreign film, movies with ambiguous endings, or just great storytelling.

11. Octavia, written by Melinda Selmys. Her short-story collection Against Nature is horror in a stricter sense (and contains some truly chilling stories, particularly ‘Catastrophic Beauty,’ ‘Rite of Atonement,’ and ‘Mother R’lyeh’), whereas Octavia is more along the lines of ‘hard fantasy,’ i.e. that kind of fantasy that is imagined as consistently as good sci-fi, of which Tolkien is the most famous example. The exploration of time, memory, secrecy, and causation in Octavia, and the dark mirror that it gives of the sacrament of Confession was creepy and fascinating to me. There were parts of it I found confusing, but the world and the people that Selmys imagines are captivating.

10. IT: Chapter One, directed by Andy Muschietti. Now, fair dues, I haven’t read the book and I only just saw the film this weekend, but I watched with a critical eye. I give the film a B+, maybe an A-: there were moments that were just a little too stereotyped to be convincing, including a few plot puzzles, although do look at this episode of Film Theory on that subject. But overall it was fantastic—the acting was superb (even though nearly all the principal characters were children), the effects were excellent without descending into mere showing off even once (such a common vice!), and the picture that it gave of the culture of childhood was remarkably good. So many books and movies try to depict children and betray only that the writers haven’t got the faintest recollection of what it was like to be a child, but IT beautifully captured the mixture of innocence, boldness, fear, sin, and that curiously rigid social code that characterize school age.

9. V/H/S, produced by Brad Miska. V/H/S is really a collection of stories within a frame, à la Boccaccio or Chaucer, rather than a single narrative; and not all of those stories are quite as good as the best of them (which, to my mind, are the first sub-frame story, ‘Amateur Night,’ and the fourth, ‘The Sick Thing That Happened to Emily When She Was Younger’). The short films are by no means cohesive, so if you don’t like anthologies then this movie is not for you; however, each of the short films is in my opinion creepy as hell in its own right, and if what you’re after is that peculiar shudder, I recommend it.

8. All Hallows’ Eve, written by Charles Williams. A unique book, penned by a devout Christian who knew a great deal more about the theory of ceremonial magic than most people do, All Hallows’ Eve depicts spiritual corruption through sorcery in a way I’ve never seen done elsewhere—plenty of people can write a morally evil character, but a character who is genuinely spiritually evil is beyond the ken of most. Williams is also rare in his power to make the reader feel that they’re dealing with unexplained but powerful realities, as opposed to the much commoner effect of making the reader feel they’re dealing with a villain whose powers the author hasn’t adequately thought out. War in Heaven, Descent Into Hell, and Many Dimensions have similar qualities, but Hallows is, narrowly, my favorite.

7. Nosferatu, directed by F. W. Murnau. This was the first vampire film, and one of the earliest surviving films, a silent movie released in 1922. Rather loosely based on Stoker’s Dracula, it retains the capacity to frighten even a modern viewer, not least because of Max Schreck’s ghastly appearance and manner as the titular vampire: no Lestat or Claudia or Armand, Nosferatu’s Count von Orlok is as visibly animal as he is practically cunning, and the blending of that human, cruel intelligence with the powers of the undead in this movie rivals anything that its modern successors have to offer.

6. Todd and the Book of Pure Evil, created by Charles Picco, Craig David Wallace, and Anthony Leo. Based on a short film of the same name, Todd is a horror-comedy set in a high school, sort of like if Buffy the Vampire Slayer were much more laden with sex jokes, poop jokes, loving tributes to death metal, and were Canadian. I tried Todd and the Book of Pure Evil more or less at random as a Netflix suggestion, and in so doing discovered one of my all-time favorite TV shows. It’s a typical monster-of-the-week format, but with writing so delightful and characters so convincing—even, a mythology so solid, for all its flippancy on the surface—that it blows most of its ostensible parallels out of the water. Not unlike Rick and Morty, one of my favorite things about it is its willingness and power to combine profoundly emotional moments and profoundly stupid (but funny!) jokes in a single episode or even a single scene.

5. The VVitch, directed by Robert Eggers. I must admit, I thought the music for The VVitch was stereotypical and overdone. On the other hand, I thought every other thing about it was just about perfect, so I’m prepared to overlook the music. The acting, the script, the periodicity, the pacing, everything was spot-on; and, most importantly, the titular witch was treated seriously: not as a pretext to critique Christianity (an intrinsically valid but all too often artistically boring pursuit) or to assert some kind of feminine spirituality, nor as a mere delusion—unless the majority of the film’s events were delusions, which is a possible and fittingly terrifying interpretation, though I don’t accept it myself—but as a real and active malice, operative both through temptation to luxury and indulgence and through temptation to paranoia and hatred, just as real evil spirits operate. (See also Eve Tushnet's review of the film in The American Conservative.)

4. Stranger Things, created by Matt and Russ Duffer. Once again this isn’t strictly horror; it’s mixed with period piece (though, the period being the eighties, the periodicity isn’t overstated, which if anything makes it better) and adventure in a rather Spielbergian vein. I’ve only just started season two, but I can definitely testify that season one, while packed with homages to older films and shows, plays with its sources and the tropes they use in a magnificently independent way. The Duffer brothers give their name the lie: practically every detail of Stranger Things is a delight of smart filmmaking.

3. The Invitation, directed by Karyn Kusama. I must also credit Phil Hay and Matt Manfredi, the writers of this film, for its brilliance. I grew up in the world of the Waco siege, the Heaven’s Gate suicides, and the scandals of the Church of Scientology, and even (or especially) as a religious person I’m sensitive to the dangers that lurk in the religious and philosophical impulses of man. The Invitation exemplifies those dangers with a realism I’ve never seen anywhere else; it freaked me out about as much as any other movie I have ever watched, with the possible exception of The Blair Witch Project—though since I do not believe in the Blair Witch but do believe in cults, I have to give this movie precedence in terms of pants-staining excellence.

2. This Book Is Full of Spiders, written by David Wong. This novel, the second in the Undisclosed trilogy, surpassed its outstanding predecessor by leaps and bounds. The peculiar brilliance of this novel is the skill Wong displays in juxtaposing the danger of the actual monsters with the danger of fear and hysteria, without minimizing either one. Many authors are all too apt to reduce or eliminate one of these dangers in the name of accenting the other; Wong, properly confident in the world he’s built and his own power as an author, follows each to its logical end in the framework of the universe he’s built, and thus he earns every victory and every horror his book contains. (Note that Spiders is better, but not at all incomprehensible, if you’ve already read the first book in the trilogy, John Dies at the End.)

1. The Babadook, directed by Jennifer Kent. In my experience, this is quite simply the best horror film that has yet been made. The script, directing, and cinematography are superb; the special effects are spot-on; the story has a wonderful balance of the primal fears of childhood and the psycho-social fears of adulthood; and the acting is, in every case, quite simply perfect. I cannot recommend this movie highly enough, and I look forward to literally anything else Kent does.

I’d also like to give an honorable, if fundamentally different, mention to my friend Eve Tushnet’s talk at the recent Doxacon gathering on The Humiliation of Authority in Horror Films, which is illuminating and engaging; I can also recommend Leah Libresco’s Wizardry and the Wounds of the World.

✠ ✠ ✠