'There are dozens of us.'

I cannot take such a view -- and not only because I happen to be a gay Catholic, as are many of my friends. However small the number of people at stake, I consider a right approach to this matter to be indispensable if the Church is to be effective in the New Evangelization. Here are some reasons why.

1. The individual, not the merely the collective, is primary.

One of the treasures of Christianity and especially of Catholicism -- a treasure that seems, somewhat paradoxically, to be more and more specifically Christian, as the globalization of modernity carries on -- is a profound sense of the primary importance of the individual. The individual is not separated from society, but he is distinct from society, and it is only through individuals that anything ever happens. Pope Benedict XVI, in his Introduction to Christianity, had this to say on the subject:

'Christianity lives from the individual and for the individual, because only by the action of the individual can the transformation of history, the destruction of the dictatorship of the milieu come to pass. It seems to me that this is the reason for what to the other world religions and to the man of today is always completely incomprehensible, namely, that in Christianity everything in the last resort hangs on one individual, on the man Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified by the milieu -- public opinion -- and who on this Cross broke this very power of the conventional "everyone," the power of anonymity, which holds man captive. ... Precisely because Christianity wants history as a whole, its challenge is directed fundamentally at the individual ...'*

That there are only a handful of gays and lesbians in the world, and that only a fraction of these are believers -- I attach no importance to these facts. God, since His mind is infinite, can pay total attention to every creature that there is -- as totally as if it were the only thing that He had created. We can't do that, of course; but we can keep in mind that His perspective is the accurate one -- we generalize and gloss over things and 'look at the big picture' because our minds are smaller than His, not because they are larger. Paying complete attention to every minuscule detail of every thing, and specially of every human being, is not only appropriate, but exactly what God does all the time. To treat a human problem as unimportant because it only affects a minority of people may sometimes be permissible, as a desperate remedy to a desperate shortage of time and resources; never otherwise.

Fundamentally, this idea of the supreme importance of persons finds its roots in the doctrine of the Trinity: the Divine Persons are as real and as distinct as the Divine Substance; the Glory equal, the Majesty co-eternal; none is afore, or after other: none is greater, or less than another. But I have neither time nor space to treat that Mystery anything like adequately -- nor the wisdom.

2. Connected to this, we -- that is, gay Christians -- need things we're not getting.

I have written of this before, and I don't claim to have a solution. I am not even totally certain what a solution would look like, except in the most general sense that living as a gay Catholic would not have the appearance (I believe, giving full force to the word believe,** that it is a false appearance) of being asked to do the impossible.

That's the thing, though: as things now are, to nearly everyone outside the Church and to a lot of people within it, telling LGBT believers that they must either enter heterosexual, cisgender marriages, or else abstain totally, sounds like a sentence to living death.

Of course, to many readers, this may seem preposterous. After all, it's exactly the same duty exacted of every believer. That is quite true; but frankly, the people who gasp in disbelief that the Christian faith could propose to exact the same duty of people who are, in this respect, dissimilar, have grasped the issue far more clearly than those whose orthodoxy is uncomprehending or uncompassionate. The equal duty here is not unlike the equal duty of, say, escaping from a flaming house: somebody without legs is inevitably going to have a far harder time with it than a legged man.

So what could the answer possibly be? A greater integration of LGBT Christians into the life of the Church? Possibly; but in that case, we need to be actively included by others -- we can't include ourselves. That is something a whole community does; a kind of conspiracy, if you will. And I know from experience that young Catholic couples can be peculiarly bad at including people who are not other young Catholic couples. The Young Papists have many virtues, truly, but imaginative sympathy with those unlike themselves is frequently not among them.

Well, alright -- what about a lay institute? That could work. The potential problems involved in getting a group of gay dudes living together probably need little explanation, however; I doubt the solution would be a universal one.

Did somebody say 'flaming house'?

The essential problem is one that Eve Tushnet noted on her blog some time ago: a man who had posed her a question while she was on a speaking tour made the poignant remark, quoting a gay friend of his, 'I just want to come first for someone.' It is this -- the profound human need to know that one is loved, worthwhile, not an intrusion, not simply put up with but actively wanted -- that many single believers (straight as well as gay) find ourselves at a loss to experience. Because, in the life of a married person, there's always someone else: the spouse, and often children, who take precedence. To be shunted toward the back of everyone's list is a bitterly disappointing experience, to the point that some of us give up entirely, and either adopt a promiscuous double-life to numb the pain, or seek out a sexually active relationship like (so it seems) everyone else has -- for even a clear conscience is very cold comfort in the face of the ultimate human pain, which is loneliness.

The actual needs of this class of human beings whom I am content to call gay Christians would, therefore, be sufficient for me to consider the intelligent, sympathetic conducting of Christian-LGBT dialogue worth doing. It is a microcosm, with its own peculiar qualities, of the basic human need for love -- something that those who aren't caught in this particular crossfire often fail to see, being caught up in the moral and the political aspects.*** As though any political stand, or even any moral one, had the smallest power to transform the human heart. Only unconditional love, that may care about, but does not define itself according to, the beliefs and conduct of the loved one, can provide the soil in which a seed may be sown and sprout.

But there is another reason why I consider this issue so vitally important.

3. This is going to dictate -- no, it already is dictating -- the course of the New Evangelization for this generation in America.

In terms of popular opinion, the tide has decidedly turned, throughout most of the West, in favor of homosexuality. The Church's stance has become incredible and even incomprehensible, and its philosophical underpinnings (to say nothing of its Biblical roots) make no difference -- not in the sense that they do not matter objectively; rather, in the sense that even those who know of and understand, say, natural law theory, are frequently more disposed to object to natural law theory as having the unacceptable consequence of condemning homosexual conduct, than to espouse the theory and thus also its logical results.

The fundamental problem is not, I think, one of relativism: it is one of a competing ethical theory, one that is gradually forming its own somewhat cohesive system, on the basis of certain -- usually quite legitimate -- moral intuitions (e.g., the equal worth of all human beings), and that partly overlaps and partly conflicts with the belief of the Catholic Church. The situation presented for the New Evangelization today is not at all like that which faced, say, European and North American societies in the mid-nineteenth century, when the question was one of recalling people from spiritual lethargy to the active practice of a Christianity into which they had already been initiated, however dispassionately. It is one of a genuine rival to Christianity -- a scientistic, typically liberal (in several senses of the word), often utopian, outlook, one that is not altogether unlike a religion though it is very unlike a church. And one of the tenets of this quasi-religion is that homosexuality is as legitimate as heterosexuality. The teaching of Scripture and of holy Tradition on the subject is not being merely ignored as a truth the World does not wish to pay attention to; the problem is not one of laxity. It is, increasingly, one of serious philosophical dispute about the real nature of sexuality, of right and wrong, and of authority. That must be respected if the Church's voice is going to be heard. There is no use whatever in telling people to listen to the Church without giving them a reason to listen to the Church; and unless they are Christians already, they don't have one.

This is why I speak so much here about dialogue rather than preaching. Most of what I hear, and have heard since childhood, from Christian sources (both Protestant and Catholic) about our nation's culture, has consisted in a sort of angry shock that non-Christians do not think and behave like Christians. I feel that we ought perhaps to have expected that. The World is not the Church. That is what 'the World' means. And being shocked at people does not, as a rule, win hearts.

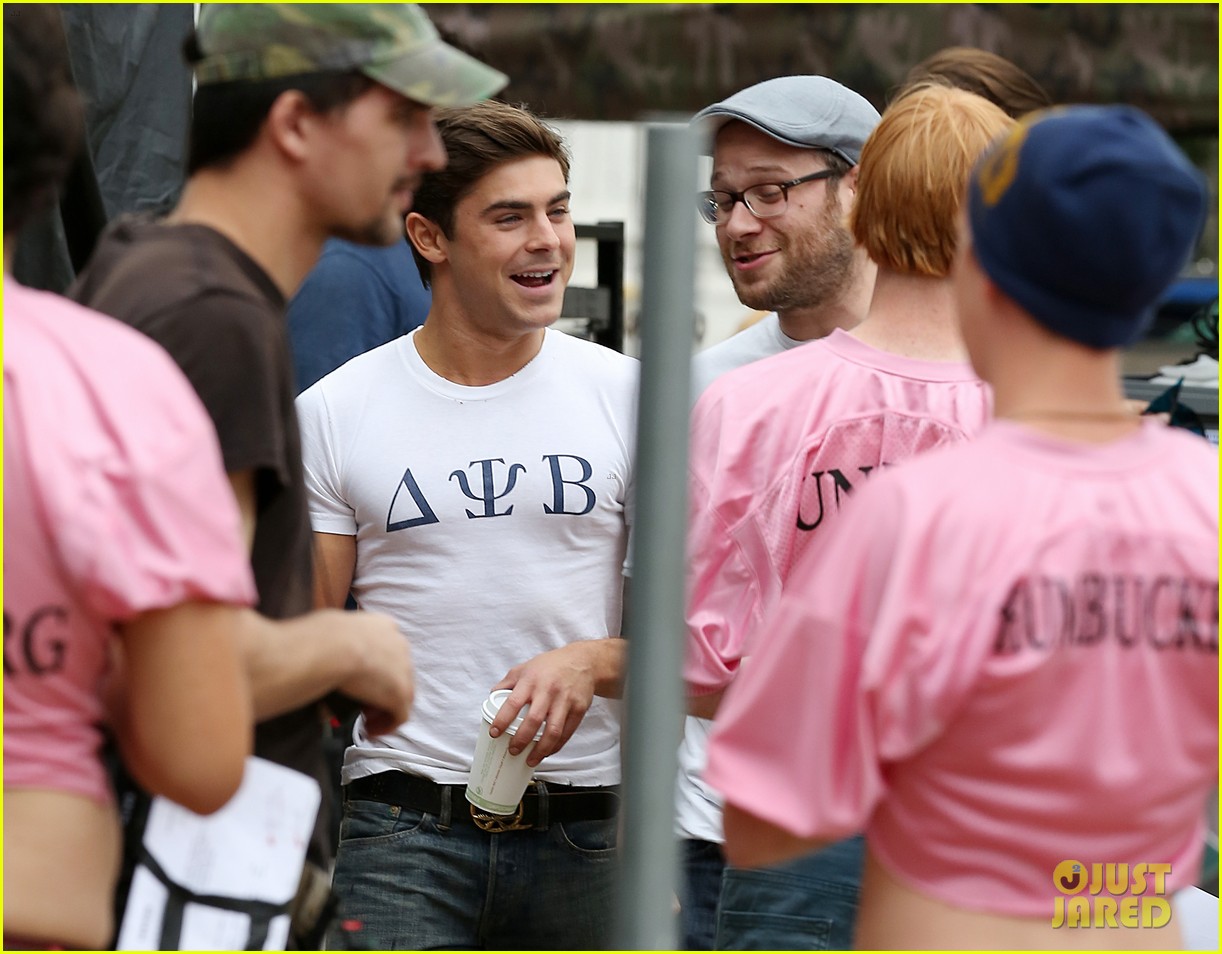

Can you spot the person who has made people feel like Christianity

is something they might be willing to touch with a ten-foot pole?

To re-evangelize countries like our own that have not merely grown slack, but actually abandoned their heritage of faith, we need something more than it's-my-ball-I'm-going-home arguments about what phrases should be in the Pledge of Allegiance or whether the Ten Commandments should be displayed in courtrooms. On gay issues, and on every issue, the fundamental thing is how to allow ourselves to be transparent windows to God, letting the light in. (And all these things shall be added unto you.)

And among the reasons we aren't succeeding much at that right now, is the fact that the Church -- that is, Christians -- have not done a good job of understanding the other side. How many believers are conversant with the real lives of gay people? And how can we expect to have any credibility with those outside if we're not? That the Church is right about the moral issue at stake, is of very little consequence; being right doesn't mean you know what you're talking about -- it doesn't give you any intrinsic insight into the lives of the people who will actually have to bear the effects of the doctrines, and those doctrines only have real existence in that personal context. There is no abstract member of 'the homosexual movement'; there are only people -- that is, images of God. Just as the Trinity is a doctrine of relationship, so chastity is a doctrine of relationship, and evangelism takes place only as a function of relationship. And relationship requires genuine understanding of the person we are relating to; treating someone simply as an example of a trend is profoundly insulting, and represents a refusal or incapacity to relate. And genuine understanding has, as one of its first prerequisites, listening to that other.

Or, to sum the matter up far more succinctly and Biblically: God is love.

*Pp. 249-250, italics original.

**The differing ways in which this clarification can be read struck me while I was writing it, and it's rather fascinating. To one sort of reader, "giving full force to the word believe" would consist chiefly in asserting that I don't actually know; to another sort of reader, it would suggest rather having complete subjective confidence in the belief I've stated. I mean both at once -- I'm quite fond of playing on words -- but it's hard to convey the distinction without a long, digressive footnote, and nobody wants that.

***Admittedly, plenty of us who are caught in precisely this conflict see little aside from the morals and politics, too.

Well, since nobody seems to be taking you up on your piece here, I may as well jump in. Let's see, how to focus this so it doesn't become a ramble...OK.

ReplyDeleteIn the midst of all your thinking this through, you hit on a chord I can somewhat relate to:

You believe the Church's morality is true, but you point out that "being right doesn't mean you know what you're talking about." That means lack of understanding of the actual effects that this "true" morality has on homosexual people who embrace it. Reminds me of Fr Rank in Greene's Heart of the Matter, who says, "The Church knows all the rules but it doesn't know what goes on in a single human heart."

The Catholic sexual axiom, its principium stantis vel cadentis, is that the only natural and non-sinful kind of sexual act is intercourse between a husband and wife that is open to procreation. Make an exception to that and the whole moral "house of cards", to use Pope Francis's expression, implodes. So the Church can never say OK to same-sex activity without destroying its axiom and self-destructing.

I sympathize, intellectually and socially. Marriage and family is sacramental for Catholics, and marriage and family is hugely and crucially important for any society. Homosexuality, a personal issue for maybe 3% of the population, is not. If protecting the foundation means inconveniencing a tiny minority, so be it. Priorities.

The side-effect of this moral structure on homosexuals, however, is unique. For heterosexual, the sexual rule says Not Now, Not With This Particular Person, Not Yet but Later, Not This Particular Act but These. For the homosexual, the rule says: Nothing. Ever.

So when, for example, I fall in love with a man, the primal urge to connect with him physically, heart and body both, is for me, as a homosexual, not at all what it feels like, but is, in reality, a sordid counterfeit and an act of violence. Use whatever nice lingo you like, but that's how it cashes out.

So, here's my question to you: if the only kind of sexual eros you are capable of is judged to be intrinsically disordered and its expression always and everywhere gravely sinful and unnatural, how do you NOT loathe yourself for this shameful defect in your nature?

As I said recently to a nice Christian, orthodox Christian morality in no way requires Christians to hate homosexual people, but given the unique effect it has on them, it's hard to see how it does not make orthodox Christian homosexuals hate themselves.

A gravely important question, and one of the mainsprings of this whole blog. A great deal of what I'm doing here is trying to come to terms, if only by thinking out loud, with how to reconcile authentic self-love (i.e., love of one's self as God's creature) with the doctrine of the Church (which I believe to be God's revelation). I can't do justice to the matter in a single comment, obviously; but I have found the following things helpful in thinking about it.

Delete1. Even on the supposition that homosexual sex is sinful -- well, there are lots of sins, and God loves sinners. All authentic love on the Divine pattern, therefore (what used to be technically called "charity"), must find some way of loving an object that has distinctly unlovable qualities. Now, I'm the first to admit that homosexuality, insofar as it is a constituent part of someone's psychology, seems like a graver issue than some other things; but I have a hunch that there's a lot less in that than we are apt to think (without dismissing it entirely, to be sure). There are much more terrible trials than homosexuality -- the go-to and rather unfortunately complex, baggage-laden example is pedophilia: I don't find it at all difficult to believe that God loves pedophiles. (Not that I wish to derail this into a love-the-sinner-hate-the-sin conversation, a phrase and a sentiment I've long disliked.) But I've begun to think that all love will have to contain some element of compassion for the flaws of its object -- some crucifixion.

2. The only things over which it is, in my view, appropriate to feel shame, are moral choices. No quality, however intimately involved in my capacity to relate, however legitimate its claim to be a part of my identity, counts. As to evaluating specific acts, there are good reasons to be gentle with oneself; as, for example, that God is; additionally, that weakness of will, ignorance, lack of wisdom, addiction, &c., are all very normal and natural things -- to say nothing of the human need for intimate love, which does include a physical dimension. An author who spent several years as a gay prostitute in New York wrote that "Sex is important, but touching another human body is even more important. It's something we all need at one time or another, and, for whatever reason, it's hard to get enough of it." But I digress. The point is, on those rare occasions when shame is appropriate, it is solely as a response to actions; and even then, it is appropriate only insofar as it acts as a spur to repentance and amendment. If one doesn't feel shame, it is dangerous and silly to try to manufacture it; if one does, it must be canalized toward those actions, and then dropped or ignored.

3. Perhaps of the greatest importance: I don't actually think that erotic love finds its true consummation in sex. I don't think sex and eros incompatible, indeed, they usually go together, but I think this is a case of correlation rather than identity. I think, based largely on my acquaintance with Dante and Charles Williams, that the true end of erotic love lies simply in the delighted contemplation of the beloved. Sexual intimacy could be a mode of such contemplation, but I don't think it necessary. One of the effects of this theory is that, while I believe gay sex is wrong, I don't necessarily condemn homoromanticism: if it is "the delighted contemplation of the beloved," the fact that the beloved happens to be same-sex wouldn't be relevant. It would affect how the love ought to be conducted, but I don't believe it would determine its moral character. This is largely a question of half-baked theories, though; I couldn't hang a whole theology of sex and romance upon it, naturally.

I appreciate your answer. We lack some common ground, of course: you accept the Church's whole moral teaching as God's Revealed Truth and I no longer do. That limits our exchange, but it’s also what makes it interesting for me in that it helps me be clearer, at least to myself.

ReplyDeleteI much respect Catholicism for its focus on the societal lynchpins of marriage and family, its resistance to the gender interchangeability program, and for its internal coherence. But I do not believe that any system of morality --including a principle-based coherence one--can do actual justice to all the human phenomena it seeks to assess and order. In fact, I suspect, any complete moral system must necessarily create injustice as its byproduct. It contains an ideological streak which strengthens its center but makes it maladaptive near the edges.

In this “fallen” world, in order to protect what is most valuable, it is virtually necessary to over-react against even distant threats to it. Take the rabbinic strategy of “building a fence around the Torah”, which forbids even the most innocent of actions –such as touching a pen on the Sabbath—which might even remotely approach breaking the Law. Natural Law plays a similar role in Catholicism by building a fence around the Sacrament. When all is said and done, it puts solitary masturbation in the same mortal sin category as adultery (or murder, for that matter). On the surface, that’s head-shakingly odd.

I don’t fault either the Rabbis or the Church for their moral systems. They are not out to be "oppressing" anyone; they are protecting what they deem most sacred. When that is the agenda, given human nature and life on planet Earth, overdoing it is well-nigh unavoidable. (Eg, the regnant secular religion of Liberalism does precisely the same thing to foster its “values”: refusing support for gay marriage is criminal because it eventually leads to gay-bashing violence and gay teen suicide, etc. )

Christian bodies who now accept homosexuality only got to that point by critically reducing their orthodoxy quotient in other areas first (female clergy as one vector) and there's no reason to believe that the anti-tradition trajectory will stop for them. So the Church, IMHO, whose moral/sacramental compass is set to marriage-family, cannot do justice to homosexual love as it is actually experienced and lived. As you say, even if they're right, they don't really know what they are talking about. But saying Gay is OK would unbalance and eventually unravel the whole system.

But since I am more than a cog in a moral wheel, I chose my own self-respect over the good of the system by leaving it. Or to put it more grandiosely, I chose spiritual exile over soul suicide.

In your reply (gentlemanly, self-critical and very rational, as usual) you accept the condemnation of homosexual acts but also seek to protect your sense of yourself as a loveable creature. As you say, a big part of your blog’s raison d’etre.

Simplifying, this is what I read:

A. Your homosexual eros is only a part, and not the most important part, of who you are.

B. You should only be ashamed of certain acts, but not of yourself.

C. We are all sinners and every kind of eros has its flaws and trials.

D. Friendship is more important than sex.

Without addressing each one (my responses would be predictable to you, I suspect), my criticism is that you compartmentalize (A&B) and minimalize (C&D) things that I would not.

Where i think we really diverge (aside from faith!) is that you greatly over-estimate the rational and greatly under-estimate the non-rational element in human nature here. That is true especially of shame. And you might easily respond that I over-estimate the natural and under-estimate the supernatural.

As it turns out, given our shared erotic nature, your problem is how to live well as a homosexual man inside the Church and mine has been how to live outside it.