The Louisiana Supreme Court has recently declared that the seal of Confession is not necessarily legal grounds to refuse to testify in court. And here we go again.

Objections to the inviolability of the confessional, in cases of the abuse of minors at least (and perhaps more), have been broached here and there since the original scandal broke in the early years of this century. This is hardly surprising, though, in my view, it is most definitely ominous. This constitutes a breach of religious liberty of the first order -- far more profound than the HHS policy on contraception, in my view: for, while the latter insists on what theologians call in technical language material cooperation with evil, this is a demand that the sacred ministers of a religion violate their oaths as priests, interfering directly with their religious duties as such. Essentially, it gives them a choice between being imprisoned and being excommunicated -- for violating the seal of Confession is one of the few sins upon which the Church imposes an automatic ban of excommunication.

The fact that the issue has been raised in this specific case is a little stupid, to my mind, given that:

1) there was certainly inappropriate conduct towards a twelve-year-old girl from an adult parishioner, but not, apparently, sexual contact as such;

2) the priest is not the accused party;

3) the victim is testifying freely;

4) the accused happens to be five years dead.

If one were trying to argue that trampling on the sanctity of religious rites and Catholic consciences were necessary in extreme cases to bring criminals to justice -- a tenable position, though I don't accept it -- one could hardly have chosen a less compelling example.

But arguments about violating the seal of Confession really and truly don't work even from a purely utilitarian perspective, to the point that I cannot understand why people suggest it in the first instance. What criminal would avail himself of the sacrament of Confession, knowing that his deeds would thereafter be brought to light? -- unless it were a criminal capable of turning himself in anyway. Moreover, in this case, the victim is testifying of her own free will, but the right of the victim to privacy must be respected as well (and in this case the demand is to know about the victim's Confessions).

One point that is often lost in these discussions is that this prevents priests from defending themselves quite as much as it prevents the law from catching penitents who have spoken of crimes in the confessional. Coincidentally, this is just such a case: the only person who stands to lose by keeping silent is the priest himself; for it must be admitted that the counsel he is reported to have given the young victim looks bad, and the only witness who can bear testimony is the girl herself. If the priest wanted to challenge her testimony or give further information or nuance, he can't. That SNAP's Director has spoken of this as "deliberately and deceptively exploit[ing] confessional confidentiality" is utterly ridiculous in that light.

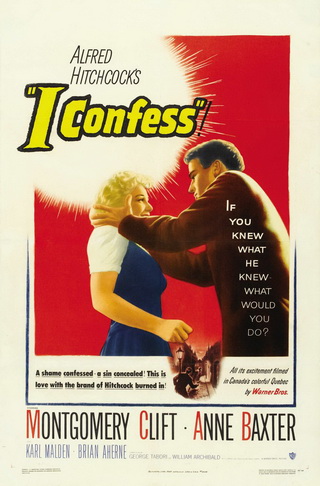

This is what comes of the decline of classic cinema.

All this is on the civil and merely practical plane. But when we turn to the specifically religious dimension, the impossibility is yet more emphatic. The priest himself, in a sense, does not forgive in this sacrament: he is, by virtue of his office, a minister of the forgiveness of God, not of his own native powers. The seal exists, and has existed for centuries, because the sins of the penitent are not the priest's own business -- he must be told them in order to give guidance, comfort, and a suitable penance, and (in extreme cases) to help him judge whether it is within his authority to administer the Divine absolution*; but none of that is his own personal affair. It is a secret even from him; even, in a sense, from God, who drowns forgiven sins in the deeps of mercy.

This is part of what the separation of church and state means. Interfering with a religious ritual on state grounds is a breach of the First Amendment of the first order. The only real recourse here is to say that the Founding Fathers, and correspondingly the Constitution, were wrong about this, and that religious liberty is neither a natural right nor appropriately a legal privilege.

To address my fellow Catholics specifically, however, I think we must be prepared -- terrible though the phrase may sound -- to get used to this. Protest and legal action in response to such attempts at violating the rights of the Church are appropriate; but I think we have gotten too cozy in the assumption that all will be well and manner of thing will be well for Christianity in the purely political sphere. We may have to acclimatize to the idea, and even the fact, of priests being jailed for refusing to divulge the existence or contents of Confessions. I say this not because we ought to apathetically resign ourselves; not even, like Job, because The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away: blessed be the name of the Lord.

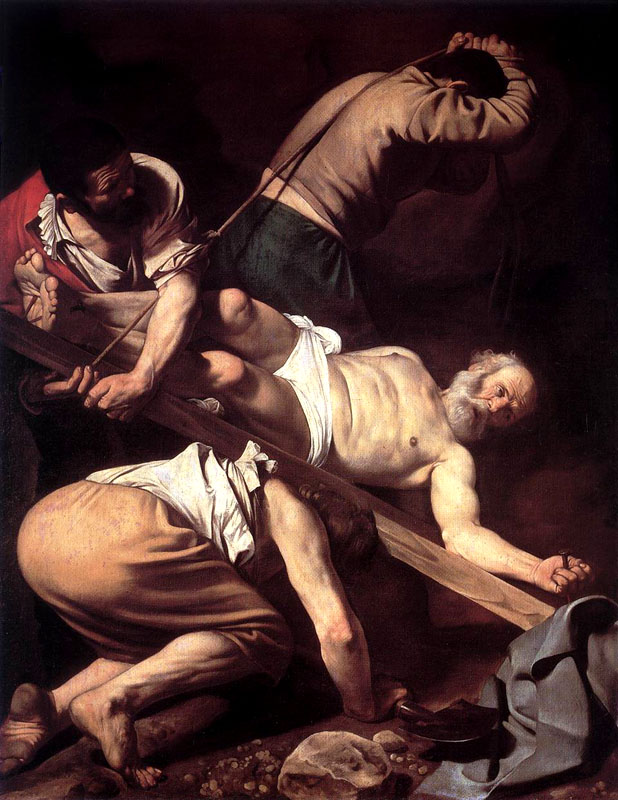

Caravaggio's Crucifixion of Peter

I say this because persecution is the natural habitat of the Church. I expect it to come around, not because our nation is specially depraved, but because it always comes around. The Church was born into persecution; nay she was conceived in the midst of it. There is nothing more persecuting that the cross. Even if we go further back, to the Incarnation itself, we find the holy Theotokos fleeing from a dangerous disgrace in her native village, with a song of joy and glory flowing from her lips; we find the Holy Child brought into the world only to escape, under St. Joseph's vigilance, into Egypt, as the shadow of Herod's soldiers fell upon the Holy Innocents. And when the Holy Ghost had fallen on the Apostles, persecution began almost immediately at the hands of the Jewish council of elders: And they departed from the presence of the council, rejoicing that they were counted worthy to suffer shame for his name. If we are persecuted for our vices, we have no legitimate complaint to make; and if we are persecuted for our virtues, then we are blessed. We must learn to expect and accept suffering, whether at the hands of the state or not; and we must pray for those who spitefully use us and persecute us, so that, as our Master said, we might be sons of our Father who is in heaven.

*The Catholic Church teaches that, as the Mystical Body of Christ animated by the Holy Ghost, she has the authority to forgive every sin. But of course, the Church is not summed up in any one person, and no one person possesses her fullness independently -- we belong to her, she does not belong to us. An example of this in the realm of administering sacramental forgiveness is that the pardon of a few sins, in the Roman Rite, is reserved to the Pope alone; breaking the seal of Confession is one such sin. (I don't know how this works in Eastern Churches, whether Catholic or Orthodox. I would suppose, on analogy, that the Patriarchs -- e.g. the Patriarch of Constantinople for Greeks or that of Alexandria for Egyptians -- probably possess something like the authority in difficult cases, but I know next to nothing about Eastern canon law.)

No comments:

Post a Comment