Tomorrow is the last day of liturgical year 2014. The First Sunday in Advent is the 30th, and that begins the new cycle of sacred time: the celebration of the Incarnation through Advent, Christmas, and Epiphany; the celebration of the redemptive work and glorification of Christ through Lent and Easter; and the celebration of the ongoing operation of Divine grace in the Church and her mysteries through Pentecost and Trinity.

The reconciliation of eternity with time -- which is closely related to the philosophical problems of free will, predestination, and Divine omniscience -- is a theme in many English Catholic and Anglican authors of whom I'm fond. T. S. Eliot's Four Quartets is a cycle of poems essentially about the interrelations of time, eternity, and redemption, opening with the problem stated from a human perspective: namely, that if all things are present to the mind of God, as He is outside of time, then how can past sins be forgiven? How can they even, in a solid sense, be called "past"?

Eliot seems to have answered this question, though I am not poetic enough or not smart enough (or both) to be sure I have grasped his answer. However, in the following, I take him to be saying that the Incarnation united not only man with God in the person of Jesus, but also the actual (including sin) with the possible (including sinlessness); so that, through the Incarnation, the intrinsic possibility of, say, St Peter remaining steadfast to confess Christ on Good Friday instead of denying Him has a kind of actuality in the mind of God -- but as I said, I'm not sure I've read Eliot correctly here.

These are only hints and guesses,

Hints followed by guesses; and the rest

Is prayer, observance, discipline, thought and action.

The hint half guessed, the gift half understood, is Incarnation.

Here the impossible union

Of spheres of existence is actual,

Here the past and future

Are conquered, and reconciled,

Where action were otherwise movement

Of that which is only moved

And has in it no source of movement ...

-- T. S. Eliot, The Dry Salvages V.29-39+ + +

II.

I must sincerely apologize to my Patreon sponsors; I promised you rewards of some unspecified kind, and I've barely started on the one I owe you all for October. Mleeaah. I am sorry. I will keep working, and hopefully have something for you soon -- thank you all so, so much for your support.

+ + +

III.

I have written a review of Wendy VanderWal-Gritter's recent book, Generous Spaciousness. I have a couple of reservations about it, but overall, I thought it was pretty good. The review can be found here at PRISM Magazine.

+ + +

IV.

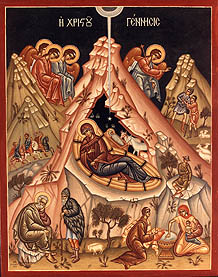

Chesterton writes about Christmas in The Everlasting Man in a way that I truly love. Though an anarchist in philosophy, I'm more of a monarchist in sentiment -- I'm extremely fond of Tolkien's remarks on the subject -- and Christmas contains what I find the most romantic strains of both loyalty and rebellion.

It is a familiar fact that the Bethlehem scene has been represented in every possible setting of time and country, of landscape and architecture; and it is a wholly happy and admirable fact that men have conceived it as quite different according to their different individual traditions and tastes. But while all have realized that it was a stable, not so many have realized that it was a cave. ... But the savor is still unmistakeable, and it is something too subtle or too solitary to be covered by our use of the word peace. ... It is not only that the very horse-hoofs of Herod might in that sense have passed like thunder over the sunken head of Christ. It is also that there is in that image a true idea of an outpost, of a piercing through the rock and an entrance into an enemy territory. There is in this buried divinity an idea of undermining the world; of shaking the towers and palaces from below; even as Herod the great king felt that earthquake under him and swayed with his swaying palace. ... [Afterward, the Church] was resented because, in its own still and almost secret way, it had declared war. It had risen out of the ground to wreck the heaven and earth of heathenism. It did not try to destroy all that creation of gold and marble; but it contemplated a world without it. It dared to look right through it as though the gold and marble had been glass.

-- G. K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man, pp. 172, 181-182+ + +

V.

Occasionally, I'll discover a new band through the XM radio playlists that are on at Starbucks; it's how I first happened to encounter Adele, Rogue Wave, and Broken Bells, for instance. (It's less common around this time of year, when it's mostly the lamer kinds of Christmas music -- not that I dislike Christmas music in itself, quite the contrary, but that they choose the lousiest stuff for some reason, including three or four different versions of "Baby It's Cold Outside," which would be annoying even if I didn't find that song kind of rapey.) Some time in October, they were playing a song called "Shells of Silver," a hypnotizing, cryptic, beautiful track, which I liked so much I looked it up, and I'm glad I did. It was by a band named the Japanese Popstars, who obviously hail from Northern Ireland. Their style is a really fascinating blend of electronica, indie, house, and ambient influences: I've never heard anything quite like it, and I actually wound up buying the whole album Controlling Your Allegiance, buying whole albums being something I rarely do. "Fight the Night" is probably my favorite track on it; "Let Go," below, is the opening track, which has more of a club-synthpop feel.

Warning: video appears to have been made by huge Guillermo del Toro fan after doing all of the acid. May be bad for soul.

No comments:

Post a Comment