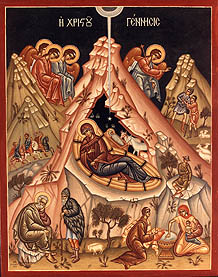

The beginning of Christendom is, strictly, at a point out of time. A metaphysical trigonometry finds it among the spiritual Secrets, at the meeting of two heavenward lines, one drawn from Bethany along the Ascent of Messias, the other from Jerusalem against the Descent of the Paraclete. That measurement, the measurement of eternity in operation, of the bright cloud and the rushing wind, is, in effect, theology.

The history of Christendom is the history of an operation. It is an operation of the Holy Ghost towards Christ, under the conditions of our humanity; and it was our humanity which gave the signal, as it were, for that operation. The visible beginning of the Church is at Pentecost, but that is only a result of its actual beginning -- and ending -- in heaven.

-- Charles Williams, The Descent of the Dove, p. 1

It's all quite straightforward.

+ + +

I'm sometimes asked why, as a gay man, I would join the Catholic Church, which is regarded -- not altogether groundlessly -- as so notoriously homophobic. More often, I've come across more general (and, in my opinion, better supported) objections to Catholicism on the basis of her history. When we consider how late the Church banned slavery, how long she accepted (in practice if not in theory) the use of torture, the variegated corruption of her prelates in much of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance -- it's easy to see how the idea that the Catholic Church is the ark of salvation and the infallible teacher of mankind is, well, a hard one to swallow.

I can say that, from the beginning, the general character of the Church never once formed a motive for my conversion. The character of individual saints did; the heroism, the unswerving devotion to principle, the mystical wisdom, and the incredible compassion of saints like Thomas More, Joan of Arc, John of the Cross, Dante, Mother Teresa, Thomas a Kempis, and Francis of Assisi made a deep impression upon me. Nor did it escape me that, even in those Protestant figures whose examples and writings I found the most profit from, like C. S. Lewis, Hannah Hurnard, and Dorothy Sayers, those elements were often at the very least wholly compatible with Catholicism -- if not far more characteristic and consistent of Catholic than of Protestant theologies.

But I also knew enough about the history of the Catholic Church to know that her children, and sometimes her shepherds, had connived in some of the greatest evils of western history. Perhaps it displays to what extent I am a child of my age, but I have always regarded the Crusade, the witch-hunt, and above all the Inquisition with the utmost loathing; and have known since childhood that all were dripping with holy water and wafted the scent of incense, though where they obtained their consecrations and their glowing coals is a little harder to know.

And it isn't right to simply dismiss that as a result of churchmen being sinners like the rest of us, nor pin it solely on people who were living inconsistently with Catholic principles. Doubtless these people were living inconsistently with Catholic principles, but that is not the point. Nor, to be blunt, is the fact of that inconsistency at all obvious to anyone who is not well-versed in both theology and history, and to be well-versed in either one is the study of decades: if the Church is infallible, and her pastors admit or even actively counsel certain things, surely those things are Catholicism?* And if those certain things are evil ... The mystery of iniquity in the Church is a great stumbling block to many who might otherwise consider her claims, and I believe that that mystery must, in justice, be recognized and mourned by Catholics. I think that repentance -- that is, apologizing to the victims of Catholics' sins, asking for forgiveness, and making what reparation we can through prayer and good works -- is the appropriate response to much of Catholic history (something of which St John Paul II set us a great example**), and an admirable expression of the coinherence of believers in the Church. We rejoice with those who rejoice, we mourn with those who mourn; and if necessary, we mourn for those who will not mourn and rejoice for those who cannot rejoice, sharing in one another's sins and merits together, as one body.

But why accept her claims in the first place?

For me, that's a difficult question to answer, not because I have so little reason to do so that I can't express it without sounding lame, but because I feel I have so much reason to do so that I can never decide where to start. So here are a few lines of thought that moved me personally to accept that the Catholic Church is what she says she is, as I accepted that Jesus is what He said He is.

One tack, commonly used by apologists, is a sort of historical-philosophical one. Beginning with the Gospels, not as inspired documents but as simple records left by people who at any rate claimed to be there,

we may arrive at the conclusion that, guided by the Holy Ghost or not, they are reliable in essentials. This would then establish some basic facts about the Person and work of "Jesus who is called Christ". Among these would be the fact that He established a Church, commissioning Apostles (from the Greek for

emissary or

ambassador, i.e., personal representatives) to propagate and govern it. He never wrote a word, and never ordered them to, that we know of -- and you may be sure the infant Church would have preserved

that like the Shroud of Turin; the only thing we know from the original sources is that He passed His own authority on to the men He appointed:

He that heareth you heareth me; and he that despiseth you despiseth me; and he that despiseth me despiseth him that sent me. And at the head of these men, He set the shuffling, impetuous, snobbish, and apostate saint: and told him that he was His own personal steward, the man on whom He would build the whole Church, holding the same authority to bind and loose as Heaven itself.

Now, in making Peter His steward (the language of Matthew 16 directly echoes the language of Isaiah 22.15-25, where God appoints a new steward on behalf of the house of David over the kingdom of Judah), Christ was not in my opinion saying that Peter, personally, was the rock of the Church. The character of St Peter, dearly as I love him, would make that too much of a howler. It seems reasonably clear to me, based on the Scriptural allusion made and the specifications of powers (some of which were applied to the Apostles more generally later on), that what He was doing was instituting an office which would serve as that basis: a function, admittedly to be filled by a man, as the Presidency of the U.S. is filled by a man, but not a personal virtue or inherent power any more than the Presidency. In other words, the function of the Rock is to be an ongoing part of the Church -- perhaps explaining why St Paul calls the Church the pillar and ground of the truth -- prevailing against the gates of Hell and binding and loosing in earth and Heaven being perpetual powers of the Body of Christ, expressed in this office because that is what Christ designated it to do.

And, conveniently, it isn't even a matter of sorting out the claims of various successors to the Apostles: not even such great prelates as the Patriarchs of Constantinople or the Archbishops of Canterbury have professed to be the Rock on which all the Church is built; nor have even the Bishops of Jerusalem or Antioch, places where St Peter was also a bishop for a time, have set forth rival claims. The only continuing office that has claimed or does claim to be one and the same with the stewards -- or, to use the Latin title, the vicars -- of Christ, is the Bishopric of Rome. One may accept or reject the claim, especially on the grounds of the immorality of many of St Peter's successors; personally I find it oddly appropriate that so many of them should be shufflers, impetuous, snobs, and apostates.

And if it is precisely the discharge of the office, not the character of the man, that receives the graces promised by Jesus, then we may -- in my opinion, should -- expect everything not covered by those graces to go wrong, even with the Popes, sooner or later. Following Peter's career, I'd say that most of them went wrong sooner, and generally later as well. I think, too, that that applies to the Church as a whole. Romano Guardini, a theologian of the last century who influenced many important figures in the Church (such as Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis), once said, "The Church is the Cross upon which Christ is crucified; and who can separate Christ from His Cross?" I think that is exactly the right way of looking at it. I might say, as a sort of supplement, that, in the Church, everything that can go wrong, will go wrong, but that there is a scarlet cord of truth that will not break, and from that scarlet cord the whole house hangs as the city crashes down around it.

And that is why I am not greatly perturbed by the real wickedness of the Church. Not because it has been misprised and exaggerated (though that's also true much of the time); not because the glories of her many saints cancel out the black marks of Raymond of Toulouse, Bernard Gui, or Torquemada. But because, trusting Jesus to be who He said He was, I trust Him to do what He said He would do: to be with you alway, even unto the end of the world.

It's all quite straightforward.

A healthy awareness of my own sinfulness doesn't hurt, either. Dorothy Sayers, with her usual biting clarity, points out in her essay The Triumph of Easter:

"Why doesn't God smite this dictator dead?" is a question a little remote from us. Why, madam, did He not strike you dumb and imbecile before you uttered that baseless and unkind slander the day before yesterday? Or me, before I behaved with such cruel lack of consideration to that well-meaning friend? And why, sir, did He not cause your hand to rot off at the wrist before you signed your name to that dirty little bit of financial trickery? You did not quite mean that? But why not? Your misdeeds and mine are nonetheless repellent because our opportunities for doing damage are less spectacular than those of some other people.***

It isn't, and isn't meant to be, a complete answer to the problem of evil. But I think it puts the problem into, shall we say, a more practical perspective.

A painter of the Umbrian school

Designed upon a gesso ground

The nimbus of the Baptized God.

The wilderness is cracked and browned

But through the water pale and thin

Still shine the unoffending feet

And there above the painter set

The Father and the Paraclete.

-- T. S. Eliot, Mr. Eliot's Sunday Morning Service, ll. 9-16

+ + +

According to their own evidence, the manifestation came. At a particular moment, and by no means secretly, the heavenly Secrets opened upon them, and there was communicated to that group of Jews, in a rush of wind and a dazzle of tongued flames, the secret of the Paraclete in the Church. Our Lord Messias had vanished in his flesh; our Lord the Spirit expressed himself towards the flesh and spirit of the disciples. The Church, itself one of the Secrets, began to be.

-- The Descent of the Dove, p. 3

.jpg)

*The reason that Catholic theology does not teach this is rather technical, but worth noting, in a woefully abbreviated form. The doctrine of the infallibility of the Church means that, when the Church invokes her full authority to preach and teach her message, the Holy Ghost protects her from any admixture of falsehood. This is true in the strictest sense of the words; note the corollaries. Those things which aren't her message -- such as nearly all scientific, most historical, and many philosophical questions -- are questions on which she has no supernatural insight; if her clergy do say anything about them, it can only be the fruit of expertise (or the lack of it), not of inspiration. And even those things which are her message, the doctrine and moral code of Christianity, are not necessarily wholly protected from error if she does not invoke her full authority, which in fact she rarely does, either in the person of the Pope or by means of an ecumenical Council. And finally, the Church is not prevented from pursuing wrong policies as ways of trying to implement the truth. Having the truth will get you somewhere, but it does not produce perfection by itself: faith, wisdom, patience, and love must greatly leaven mere correctness, or it is apt to do a great deal more harm than good.

**Having been the victim of abuse myself (though not at the hands of a priest), I am not insensitive to the criticisms of St John Paul's pontificate on this score. It was, in my opinion, a great and serious flaw. But I do not believe that any great man is free of flaws; and I think that his personal expressions of grief and apology for the many sins of the Church throughout history should not be accounted any less sincere, or any less worthy of imitation, on the grounds that His Holiness was not perfect either.

***From the collection Creed or Chaos?, p. 19. The essay goes on to grapple with the problem of evil in much greater detail from a Christian viewpoint, in the context of the Crucifixion and Resurrection.

.jpg)

.jpg)