What follows are some suggested meditations for Holy Week, taken from a number of English authors (two Catholics and five Anglicans), as well as some selections from the Litany and the Collects of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. I'll be trying to reduce my time online this week, and am planning to be entirely off for the Triduum (Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday), so this will be my last update until after Easter; for the same reason, I won't be approving comments for a little while, though of course readers are still free to leave them if they don't mind waiting to see them published.

Fig Monday (March 30th)

Named for the famous incident in which Jesus blasted the fig tree -- His sole miracle of destruction -- this is also the date (ritually, at least; the precise chronology of Holy Week in history is notoriously difficult to work out from the Gospels) of the cleansing of the Temple.

At the back of the Christian moral code we find a number of pronouncements about the moral law, which are not regulations at all, but which purport to be statements of fact about man and the universe, and upon which the whole moral code depends for its authority and its validity in practice. These statements do not rest on human consent; they are either true or false. If they are true, man runs counter to them at his own peril. He may, of course, defy them, as he may defy the law of gravitation by jumping off the Eiffel Tower, but he cannot abolish them by edict. Nor yet can God abolish them, except by breaking up the structure of the universe, so that in this sense they are not arbitrary laws. ... There is a difference between saying: "If you hold your finger in the fire you will get burned" and saying, "If you whistle at your work I shall beat you, because the noise gets on my nerves." The God of the Christians is too often looked upon as an old gentleman of irritable nerves who beats people for whistling. This is the result of a confusion between arbitrary "law" and the "laws" which are statements of fact. ... Scattered about the New Testament are other statements concerning the moral law, many of which bear a similar air of being arbitrary, harsh, or paradoxical: "Whosoever will save his life shall lose it"; "to him that hath shall be given, but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath"; "it must needs be that offenses come, but woe unto that man by whom the offense cometh" ... We may hear a saying such as these a thousand times, and find in it nothing but mystification and unreason; the thousand and first time, it falls into our recollection pat upon some vital experience, and we suddenly know it to be a statement of inexorable fact. ... The cursing of the barren fig-tree looks like an outburst of irrational bad temper, "for it was not yet the time of figs"; till some desperate crisis confronts us with the challenge of that acted parable and we know that we must perform impossibilities or perish.

-- Dorothy Sayers, The Mind of the Maker pp. 8-10

From all evil and mischief; from sin, from the crafts and assaults of the devil; from thy wrath, and from everlasting damnation,

Good Lord, deliver us.

From all blindness of heart; from pride, vain-glory, and hypocrisy; from envy, hatred, and malice, and all uncharitableness,

Good Lord, deliver us.

From fornication, and all other deadly sin; and from all the deceits of the world, the flesh, and the devil,

Good Lord, deliver us.

From lightning and tempest; from plague, pestilence, and famine; from battle and murder, and from sudden death,

Good Lord, deliver us.

From all sedition, privy conspiracy, and rebellion; from all false doctrine, heresy, and schism; from hardness of heart, and contempt of thy Word and Commandment,

Good Lord, deliver us.

By the mystery of thy holy Incarnation; by thy holy Nativity and Circumcision; by thy Baptism, Fasting, and Temptation,

Good Lord, deliver us.

By thine Agony and bloody Sweat; by thy Cross and Passion; by thy precious Death and Burial; by thy glorious Resurrection and Ascension; and by the coming of the Holy Ghost,

Good Lord, deliver us.

In all time of our tribulation; in all time of our wealth; in the hour of death, and in the day of judgment,

Good Lord, deliver us.

-- From the Litany

Temple Tuesday (March 31st)

Named for the time before Passover that Jesus spent in the Temple court teaching. The many parables of Holy Week, the challenges from and to the Pharisees and Sadducees, and the Seven Woes are associated with this day.

Of all that was done in the past, you eat the fruit, either rotten or ripe.And the Church must be forever building, and always decaying, and always being restored.For every ill deed in the past we suffer the consequence:For sloth, for avarice, gluttony, neglect of the Word of GOD,For pride, for lechery, treachery, for every act of sin.And of all that was done that was good, you have the inheritance.For good and ill deeds belong to a man alone when he stands alone on the other side of death,But here upon earth you have the reward of the good and ill that was done by those who have gone before you.And all that is ill you may repair if you walk together in humble repentance, expiating the sins of your fathers;And all that was good you must fight to keep with hearts as devoted as those of your fathers who fought to gain it.The Church must be forever building, for it is forever decaying within and attacked from without;For this is the law of life; and you must remember that while there is time of prosperityThe people will neglect the Temple, and in time of adversity they will decry it.

-- T. S. Eliot, Choruses from 'The Rock' II.25-37

That it may please thee to succor, help, and comfort all that are in danger, necessity, and tribulation,

We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.

That it may please thee to preserve all that travel by land or water, all women laboring of child, all sick persons, and young children; and to show thy pity upon all prisoners and captives,

We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.

That it may please thee to defend, and provide for, the fatherless children, and widows, and all that are desolate and oppressed,

We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.

That it may please thee to have mercy upon all men,

We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.

That it may please thee to forgive our enemies, persecutors, and slanderers, and to turn their hearts,

We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.

That it may please thee to give and preserve to our use the kindly fruits of the earth, so as in due time we may enjoy them,

We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.

That it may please thee to give us true repentance; to forgive us all our sins, negligences, and ignorances; and to endue us with the grace of thy Holy Spirit, to amend our lives according to thy holy Word,

We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.

-- From the Litany

Spy Wednesday (April 1st)

Giotto, The Arrest of Jesus and Kiss of Judas, 1306

This day is named for Judas Iscariot. When exactly he conferred with the Sanhedrin and agreed to betray Jesus to them is not known; Matthew and John seem to imply that the anointing of Christ at Bethany, which seems to have happened before the triumphal entry, spurred his decision.

But presently [Eve] remembers that the fruit may, after all, be deadly. She decides that if she is to die, Adam must die with her; it is intolerable that he should be happy, and (who knows?) with another woman when she is gone. I am not sure that critics always notice the precise sin which Eve is now committing, yet there is no mystery about it. Its name in English is Murder. ... If the precise movement of Eve's mind at this point is not always noticed, that is because Milton's truth to nature is here almost too great, and the reader is involved in the same illusion as Eve herself. ... Thus, and not otherwise, does the mind turn to embrace evil. No man, perhaps, ever at first described to himself the act he was about to do as Murder, or Adultery, or Fraud, or Treachery, or Perversion; and when he hears it so described by other men he is (in a way) sincerely shocked and surprised. Those others 'don't understand.' ... If you or I, reader, ever commit a great crime, be sure we shall feel very much more like Eve than like Iago.

-- C. S. Lewis, A Preface to 'Paradise Lost', pp. 125-126

Almighty God, we beseech thee graciously to behold this thy family, for which our Lord Jesus Christ was contented to be betrayed, and given up into the hands of wicked men, and to suffer death upon the cross, who now liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end. Amen.

-- First Collect for Good Friday

Maundy Thursday (April 2nd)

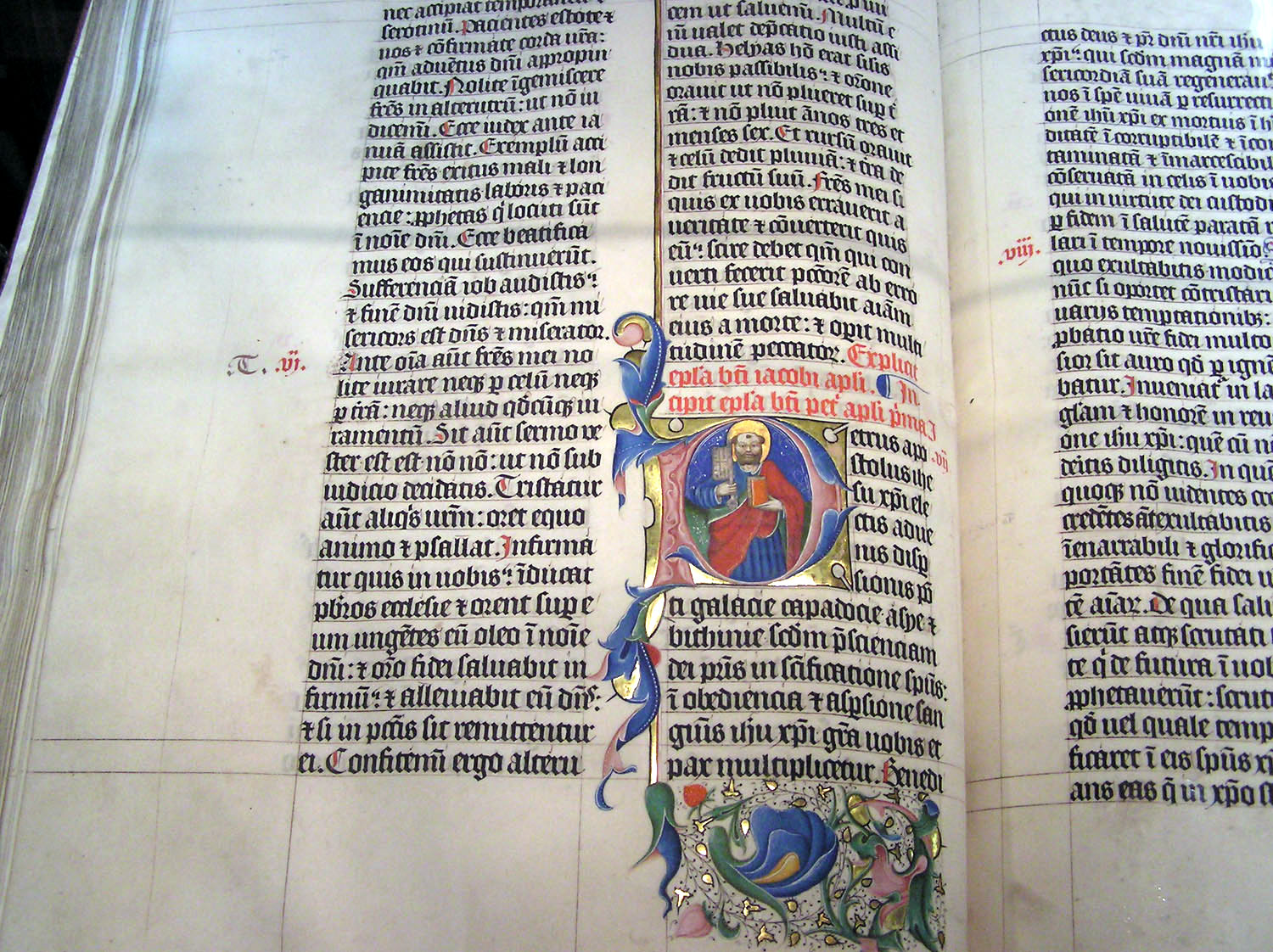

The name maundy is an English slurring of the Latin mandatum, which means 'command,' and appears in the Vulgate phrase Mandatum novum do vobis, or, in English, 'A new command I give unto you'. The original consecration of the Eucharist, and the subsequent delineation of the New Covenant, took place on this night; it is now the first night of the Triduum, the apex of the liturgical year -- a solemn celebration that takes place over three days, commemorating the institution of the Mass and the priesthood, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection.

He determined to be incarnate by being born; that is, he determined to have a mother. His mother was to have companions of her own kind; and the mother and her companions were to exist in an order of their own degree, in time and place, in a world. They were to be related to him and to each other by a state of joyous knowledge; they were to derive from him and from each other; and he was to deign to derive his flesh from them. ... But what did happen? The web depended on its exchanged derivation, which itself sprang from the fact not only that all derived from him but that he had ordained that he, in his flesh, would derive from all. The two derivations were, in him, a single act ... Somewhere, somehow, the web loosed itself from its center -- also by its free choice. ... Sin had come into the great co-inherent web of humanity; say rather that all the web burst into sin, and broke or was antagonized within itself; knot against knot, and each filament everywhere countercharged within itself. It broke? alas, no; it could not break unless its maker consented that it should and he would not consent; his good will towards it ... was too great. He loved it; he had loved it in the making and he loved it made ... No; she had turned from him; she had attempted to deracinate her life; but he was still her root, and she should still have at her disposal all that he had given her; she should still have life. Intolerable charity!

-- Charles Williams, The Forgiveness of Sins, pp. 120-122, 128

Almighty and everlasting God, by whose Spirit the whole body of the Church is governed and sanctified: Receive our supplications and prayers, which we offer before thee for all estates of men in thy holy Church, that every member of the same, in his vocation and ministry, may truly and godly serve thee; through our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Amen.

-- Second Collect for Good Friday

Good Friday (April 3rd)

Matthias Grunewald, The Crucifixion, ca. 1501

Words fail me. Chesterton can take over.

In this story of Good Friday it is the best things in the world that are at their worst. ... It was, for instance, the priests of a true monotheism and the soldiers of an international civilization. Rome, the legend, founded upon fallen Troy and triumphant over fallen Carthage, had stood for a heroism which was the nearest that any pagan ever came to chivalry. ... But in the lightning flash of this incident, we see great Rome, the imperial republic, going downward under her Lucretian doom. ... Rome was almost another name for responsibility. Yet [Pilate] stands forever as a sort of rocking statue of the irresponsible. ... There too were the priests of that pure and original truth that was behind all the mythologies ... It was the most important truth in the world; and even that could not save the world. ... The Jewish priests had guarded it jealously in the good and the bad sense. ... They were proud that they alone could look upon the blinding sun of a single deity; and they did not know that they had themselves gone blind. ... And as it was with these powers that were good, or at least had once been good, so it was with the element which was perhaps the best, or which Christ himself seems certainly to have felt as the best. The poor to whom he preached the good news, the common people who heard him gladly ... there was present in this ancient population an evil more peculiar to the ancient world. ... It was the soul of the hive; a heathen thing. The cry of this spirit also was heard in that hour, 'It is well that one man die for the people' ... that the one universal human spirit might suffer a universal condemnation; that there might be one deep, unanimous chorus of approval and harmony when Man was rejected of men. There were solitudes beyond where none shall follow. ... Nor is it easy for any words less stark and single-minded than those of the naked narrative even to hint at the horror of exaltation that lifted itself above the hill. ... [A] cry was driven out of that darkness in words dreadfully distinct and dreadfully unintelligible ... and for one annihilating instant an abyss that is not for our thoughts had opened even in the unity of the absolute; and God had been forsaken of God.

-- The Everlasting Man, pp. 210-212

O merciful God, who hast made all men, and hatest nothing that thou hast made, nor wouldest the death of a sinner, but rather that he should be converted and live: Have mercy upon all Jews, Turks, Infidels, and Heretics, and take from them all ignorance, hardness of heart, and contempt of thy word; and so fetch them home, blessed Lord, to thy flock, that they may be saved among the remnant of the true Israelites, and be made one fold under one shepherd, Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Spirit, one God, world without end. Amen.

-- Third Collect for Good Friday

Holy Saturday (April 4th)

The only thing we are specifically told happened the day after the Passion is that the surviving disciples and the Holy Family rested on the Sabbath as the Torah required. However, it's also hinted that the Lord did something in the realms of the dead at this time, which the Mediaeval Church developed in speculation and art into the awesomely-named tradition of the Harrowing of Hell. No liturgy celebrates this, however; the only liturgy this day is the Easter Vigil, the glorious climax of the Triduum and the very beginning of the Easter season. (This is the time when adult converts, having been catechized over the preceding months, are normally baptized as Catholics.)

For if all the pains contained in hell, on earth, and in purgatory -- including death and all -- were set before us, we ought rather to choose all that pain than sin itself ... And I was shown no harder hell than sin, for of its very nature, the soul knows no other hell but sin. Yet fixing our intent in love and meekness we are made all fair and clean by the working of mercy and grace. For as mighty and as wise as God is to save us, so is he most willing; it is Christ himself who is the ground of all Christian law, and he taught us to do good as against evil. In this we see that he himself is that love, for he does to us as he bids us do to others ... Inasmuch as his love is never broken toward us when we sin, so does he will that it is never broken within ourselves or toward our fellow Christians; rather we should hate the sin itself but endlessly love every soul as God loves it.

-- Lady Julian of Norwich, The Revelation of Divine Love, Thirteenth Showing

Grant, O Lord, that as we are baptized into the death of thy blessed Son our Savior Jesus Christ, so by continually mortifying our corrupt affections we may be buried with him; and that, through the grave, and gate of death, we may pass to our joyful resurrection; for his merits, who died, and was buried, and rose again for us, thy Son Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

-- Collect for Easter Eve

Easter Sunday (April 5th)

Caravaggio, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 1602

The Resurrection, I presume, calls for little explanation. Or more accurately, little that I'm equipped to give. I'll only note that the first eight days of Easter, from this day through the following Sunday, are treated by the liturgy as one: eternity invading time, heaven breaking into the terrestrial plane, in the act of the Resurrection. This is why the number eight -- one step outside the seven-day week that forms the standard measurement of time on earth -- is often a symbol in Christianity of eternity.

Here saies S. Augustine, when the soule considers the things of this world ... She rests upon such things as she is not sure are true, but such as she sees, are ordinarily received and accepted for truth: so that the end of her knowledge is not Truth, but opinion ... But saies he, when she proceeds in this life to search into heavenly things ... The beames of that light are too strong for her, and they sink her, and cast her downe ... and so she returns to her owne darknesse, because she is most familiar, and best acquainted with it; Non electione, not because she loves ignorance, but because she is weary of the trouble of seeking out the truth, and so swallowes even any Religion to escape the paine of debating, and disputing ... But then in her Resurrection, her measure is enlarged, and filled at once; There she reads without spelling, and knowes without thinking, and concludes without arguing ... What a death is this life! what a resurrection is this death! For though this world be a sea, yet (which is most strange) our Harbour is larger than the sea; Heaven infinitely larger than this world. For, though that be not true, which Origen is said to say, That at last all shall be saved, nor that evident, which Cyril of Alexandria saies, That without doubt the number of them that are saved, is far greater than of them that perish, yet surely the number of them, with whom we shall have communion in Heaven, is greater than ever lived at once upon the face of the earth ... In Heaven we shall have Communion of Joy and Glory with all, alwaies; Ubi non intrat inimicus, nec amicus exit, Where never any man shall come in that loves us not, nor go from us that does.

-- John Donne, Evening Sermon at St. Paul's on Easter Day, March 28, 1624

Almighty God, who through thine only-begotten Son Jesus Christ hast overcome death, and opened unto us the gate of everlasting life: We humbly beseech thee, that as by thy special grace preventing us thou dost put into our minds good desires, so by thy continual help we may bring the same to good effect; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end. Amen.

-- Collect for Easter Day