Surely this man's opinion will be ... something.

The city hasn't changed as much as I expected it to under the curfew. It's quieter, although there do seem to be a few more sirens than usual in the small hours; then again, maybe it's just easier to pick them out over the lack of background noise. I feel like I've seen a lot more people on foot, too, though that probably has more to do with the improved weather. I went walking around myself on Wednesday morning, and the air smelled like tulips and honeysuckle.

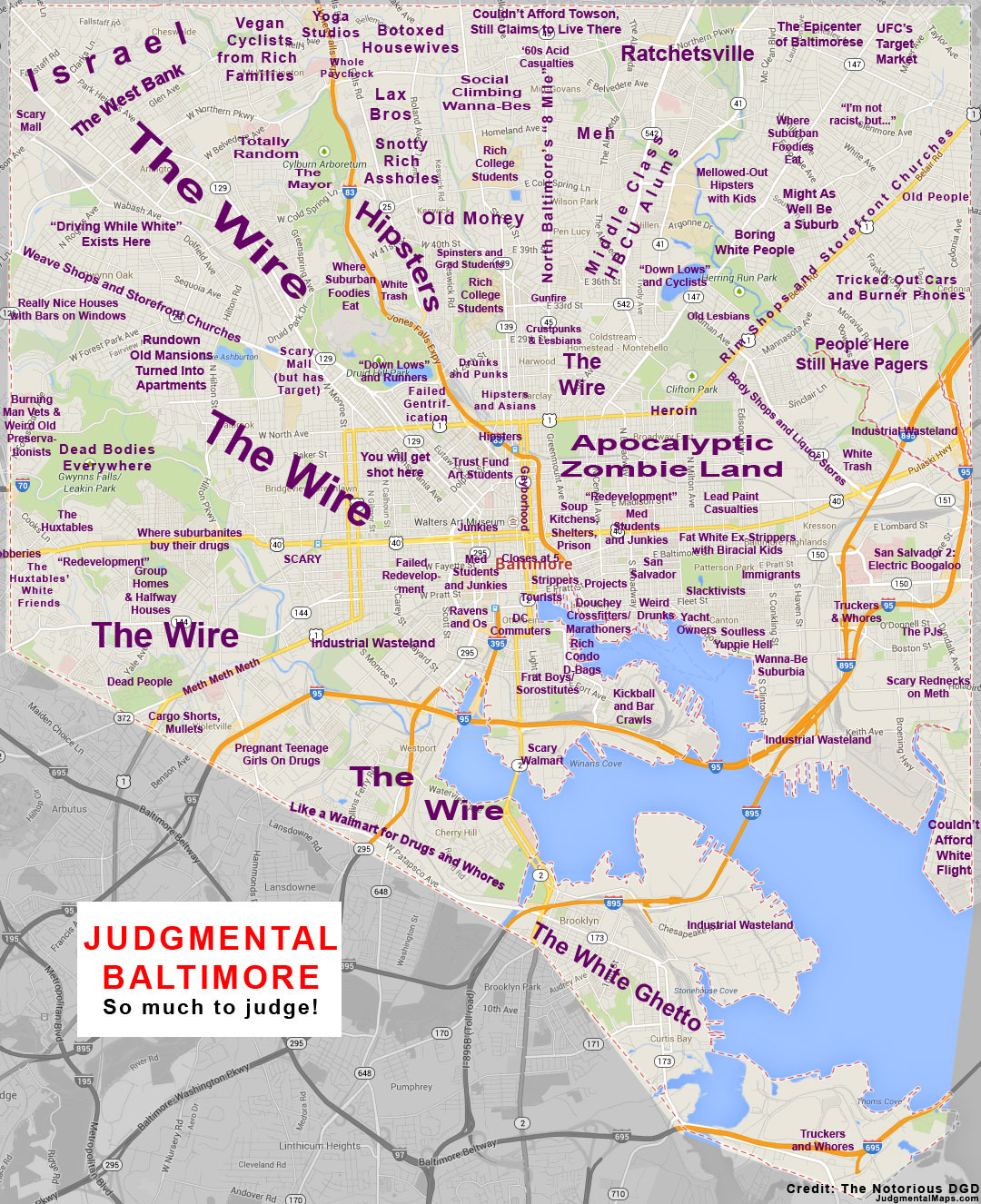

I didn't see that much damage from the riots. A few broken windows and boarded up storefronts, which aren't exactly uncommon in most of Baltimore. But of course, the neighborhood I live in wasn't in the thick of things -- it's in the center of the city, whereas most of the rioting and looting was in the west and southwest.

That's me, in between "Trust Fund Art Students," "Junkies," and "The Gayborhood."

(Image credit: The Notorious DGD, Judgmental Maps)

The thing I've been most unsettled by has not been the riots. It's been the media reaction (both mass and social media). I try to maintain a healthy skepticism of my own insights on topics like this -- I'm white, I was raised in the middle class, I was out of the city on Monday night, and I've only lived in Baltimore for a bit less than two years, after all. But some of the responses to the events of the last few days seemed, to me, to be so off-base and bizarre that I felt a reply was worth making, for whatever my thoughts are worth.

First, it's important to note that, while the riots got a lot of attention, the vast majority of protesting in the wake of Freddie Gray's sad death has been peaceable. It started that way, and most of it stayed that way. I've seen it suggested that the looting and arson happened at the hands of crooks and delinquents who merely took advantage of the moment, rather than at the hands of any protesters at all; I'm not sanguine that that's completely true, but I'd be willing to bet that the overlap was a lot smaller than you'd think from watching the news. What's more, the cleanup seems to have gone swimmingly; I met a dude on Tuesday, the day after the worst of it, while looking to help with repair work and the like, and we couldn't find anything to do. (My suspicion is that what work was still left was in the areas where the roads were still shut down, which were too far out for either of us to walk, but still.) People have been coming out of the woodwork to put their city back together, and I gotta say, I'm kind of amazed. This place is more resilient than I gave it credit for.

And I believe it's that renewal that is going to triumph in Baltimore in the end, because that is the force of life, God's creation. And that creative energy isn't just a pleasanter thing than the anti-energies of destruction, oppression, and decay; it's a stronger thing. Rampage and violence cannot make, and they begin to collapse from within as soon as they come into being; they can only continue as long as the host in which they are burrowing parasites remains vital. Life, in God, is self-regenerating. That's why it's going to win.

Secondly, the riots may have been sparked by the Freddie Gray case, which is bad enough in itself -- a nearly-severed spine is no joke, especially after being stopped and searched for, um, running away from police (who weren't detaining him, or even talking to him), who took this as a reason to chase him. I feel like the Fourth Amendment got lost somewhere in here, since running away from police who happen to be around, as opposed to police who are actively detaining you, is not to my knowledge unlawful,* and seems to me more like plausible cause than probable cause, given the whole presumption of innocence thing and the "seriously, butt the hell out of private citizens' business" thing that the American law system is sort of based on ...

Hey, it's one of those fancy napkins people use for eating Irish babies.

Anyway, the riots may have been sparked by the Freddie Gray case. But they aren't, simply, about his death. Neither are they simply about the string of highly-publicized deaths of black persons at the hands of police over the last year, although I feel sure that's relevant. Nor can we simply say "Racism" and be done, though there is plenty of that to go around so no one has to feel left out.

The occasional remarks about "black protesters" and "black rioters" that I've seen on social media have kind of creeped me out, to say the least. It's not clear to me that looting the mall or setting fire to CVS would be somehow different if white people were doing it, or Latinos, or Asians. On the other hand, I've seen one or two people more or less excusing the violence as an expression of frustration on the part of the black populace, and even referring to it as some sort of just reprisal against the white, capitalist establishment.**

The problems with all this armchair activism are manifold. Does anyone seriously propose the belief that the only people who were out looting were all black? Or that, even if every single one of them was, their skin color was somehow gremlinizing their brains to make them do it? And conversely, if this was revenge against wealthy whitey, why is it that, of the damaged stores close to my neighborhood at least, all except one were owned, operated, and frequented by local African-American folks? Or, if we propose that the class element had more to do with it, why did they loot Mondawmin Mall (i.e., scary-yet-Target-having mall as above), as opposed to the banks or restaurants or businesses close to the Inner Harbor? It's questions like these that make me think that, though there was very possibly some overlap between protesters and purgers, the latter were for the most part taking advantage of the moment.

But besides that, this has prodded me to start trying to understand racism in America better. I think it's worth pointing out that it's this power to understand which is one of the great difficulties, but maybe not for the reasons that a lot of people think. Most conservatives seem to think that liberals just enjoy being moral indignant, while most liberals seem to think that conservatives are at least a little bit supremacist. I don't think either hypothesis is necessary -- or, insofar as we kind of need everybody working on this problem, productive.

A few years ago, I was having a conversation with a friend of mine, Nazim, a guy I knew from college, whose mother was white and whose father was Algerian; he looked pretty much Caucasian if he shaved, but when he grew his beard out he looked Arabic -- handsome dude. Now, I had always thought of racism as a belief, held consciously or (I could allow this) unconsciously, that one race was superior to others -- generally one's own.

With, uh, certain odd exceptions.

Nazim, however, talking about a class he'd had where they had been discussing the phenomenon of white privilege, and about his own experience of getting white privilege if he was clean-shaven, until people learned his name (after which he'd be treated as Arabic instead of white -- i.e., not necessarily worse, but perceptibly differently). As the conversation progressed, it came out that when Nazim's professor had spoken about racism, the point had not been about any beliefs at all, conscious or submerged, but about the systemic facts of who holds the power.

In other words, an imaginary city in which two-thirds of the people are black and also happen to be largely disadvantaged, while one-third of the people are white and also happen to be largely well-off, is still (by this definition) a racist city even if none of the white folks are intentionally being dicks about it. And honestly, while I think that a person's principles and intentions are even more important than what happens, what happens is still pretty damn important.

As far as white people intentionally being dicks goes, though, I think we have to allow that there's a great deal of that. I've kept fairly quiet on most of the recent, highly publicized cases in which a racist element has been proposed*** -- Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner -- because I haven't known many of the facts, and I don't want to be a bandwagoneer, to say nothing of wishing to believe in the innocence of the cops in question until their guilt is proven (partly due to my aforesaid ignorance, and partly because these deaths were bad enough even if they were the result of horrible misunderstandings, let alone if they were callous murders). But. While I don't propose to decide on any of these things individually, the Ian Fleming rule of thumb remains: Once is happenstance, twice is coincidence, three times is enemy action. Further examination -- of facts, and of consciences -- is warranted.

And what then? I haven't got a fucking clue. I can try to do right by my neighbor in a given situation; how to help with systemic racism, even in my immediate neighborhood, I simply don't know. I will, therefore, conclude with the following excerpts from Mahatma Gandhi's Non-Violent Resistance, asking my readers -- if there are any who have committed violence, approved of violence, or excused violence as a black reaction to white oppression, and also all my other readers -- to consider them carefully.

Reader: Why should we not obtain our goal, which is good, by any means whatsoever, even by using violence? Shall I think of the means when I have to deal with a thief in the house? ... You seem to admit that we have received nothing, and that we shall receive nothing by petitioning. Why, then, may we not do so by using brute force? ...Editor [Gandhi]: ... I have used similar arguments before now. But I think I know better now, and I shall endeavor to undeceive you. Let us first take the argument that we are justified in gaining our end by using brute force because the English gained theirs by using similar means. ... [B]y using similar means we can only get the same thing that they got. You will admit that we do not want that. Your belief that there is no connection between the means and the end is a great mistake. Through that mistake even men who have been considered religious have committed grievous crimes. ... [T]here is just the same inviolable connection between the means and the end as there is between the seed and the tree. I am not likely to obtain the result flowing from the worship of God by laying myself prostrate before Satan. If, therefore, anyone were to say: "I want to worship God; it does not matter that I do so by means of Satan," it would be set down as ignorant folly. We reap exactly as we sow. ... If I want to deprive you of your watch, I shall certainly have to fight for it; if I want to buy your watch, I shall have to pay for it; and if I want a gift, I shall have to plead for it; and, according to the means I employ, the watch is stolen property, my own property, or a donation. ... Will you still say that means do not matter?

Passive resistance is a method of securing rights by personal suffering; it is the reverse of resistance by arms. When I refuse to do a thing that is repugnant to my conscience, I use soul-force.**** For instance, the Government of the day has passed a law ... I do not like it. If by using violence I force the Government to repeal the law, I am employing what may be termed body-force. If I do not obey the law and accept the penalty for its breach, I use soul-force. It involves sacrifice of self. Everybody admits that sacrifice of self is infinitely superior to sacrifice of others. Moreover, if this kind of force is used in a cause that is unjust, only the person using it suffers. He does not make others suffer for his mistakes. ... If man will only realize that it is unmanly to obey laws that are unjust, no man's tyranny will enslave him.

Reader: I deduce that passive resistance is a splendid weapon of the weak, but that when they are strong they may take up arms.Editor [Gandhi]: This is gross ignorance. Passive resistance, that is, soul-force, is matchless. ... What do you think? Wherein is courage required -- in blowing others to pieces from behind a cannon, or with a smiling face to approach a cannon and be blown to pieces? ... Believe me that a man devoid of courage and manhood can never be a passive resister. This, however, I will admit: that even a man weak in body is capable of offering this resistance. One man can offer it just as well as millions. Both men and women can indulge in it. ... Control over the mind is alone necessary, and when that is attained, man is free like the king of the forest and his very glance withers the enemy. Passive resistance is an all-sided sword, it can be used anyhow; it blesses him who uses it and him against whom it is used. ... It never rusts and cannot be stolen. ... It is strange indeed that you should consider such a weapon to be a weapon merely of the weak.

-- Non-Violent Resistance (Satyagraha), pp. 9-11, 17-18, 51-52

*It's true that Freddie Gray was found to have a switchblade in his pocket, which Maryland law only permits to be carried openly. Then again, it was his spine that got almost severed, not the cops'. And, again, the only reason they found the switchblade (which he shouldn't have been carrying) was because they searched him, and they were searching him without probable cause -- on the grounds that he ran away when he saw them, which is not proof or even very sound evidence of anything.

**I've been especially puzzled by the vitriol I've seen directed at Mayor Rawlings-Blake. Being an anarchist, I have no special attachment to the Mayor, but the hate she's gotten for her handling of the situation baffles me, especially for her remark that the violent looters were "thugs" -- a statement that one person I know literally equated with calling them niggers. We did all notice at some point, I hope, that Stephanie Rawlings-Blake is black, and therefore likely wasn't making a euphemistic racial slur? And as for thuggery, if smashing windows, stealing stuff, and setting buildings on fire doesn't count, I'd be both interested and a little scared to learn what does.

***I don't for one moment believe that the recent spate of cases that the media have latched onto are the only ones; and in fact I have difficulty believing that this string of putatively racist cop cases is even a new phenomenon. My personal hunch is that, for whatever reason, it's become sexy to report on these things, and so they found a trend that already existed and started to make a media sensation out of it.

****This translates the Sanskrit term satyagraha, a difficult word to render in English -- truth force or insistence on truth would be alternates to the translation used by Gandhi here. It is arguably the key concept in all of his thought, and was a major influence on the anti-racist and civil rights activism of Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King Jr. A more extensive treatment of it can be found here.

!["She [Gertrude Stein] got so that she looked like a Roman Emperor, which is fine if you like your women to look like Roman Emperors." -- Ernest Hemingway](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/86/Gertrude_stein.jpg)

.png)