We were in love and a child seemed absolutely necessary. Not because it was expected or because we loved kids. It was more about how much we loved each other. She couldn’t let me sleep, and I’d follow her around everywhere when I was awake. That’s what the cool people who mock breeders don’t understand: that there can be a love bigger than two people. And it swells and spills when you’re together. We wanted a baby to share because not having a child seemed wasteful.

… I stared around the corridor to see her still in her white silk nightgown dancing in our living room. Swaying and spinning like a ballerina angel, the soft fabric of her gown flowing behind, following her motions. Quick and sudden. Erratic, if not so graceful. And though her body moved in long fluid glides, I was struck by her arms, which stayed folded at her chest. I expected exaggerated sweeps and points, but she held them tight.

And then I realized she was holding our baby. Our baby that was never born, but in the still of her arms, it could not have been more real, and she spun and spun and swayed and never let it go. And no matter how tightly she held her arms, the emptiness could not contain all the love that poured from her.

This animal, this thing begotten in a bed, could look on Him.

—C. S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters XXXI

✠ ✠ ✠

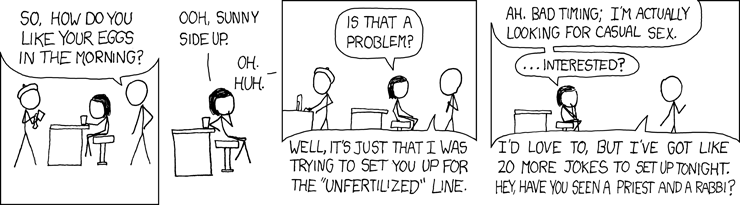

Courtesy of Randall Munroe and his dislike of copyright law.

My last post addressed some major reasons that I’m Side B, as opposed to Side X or Side Y (terms explained in the first post); the post before that, on the clobber passages, dealt with part of the reason I’m Side B rather than Side A. But I said there that the clobber passages form only a small part of my reason for espousing a traditional view of sexual ethics. I’d like to get into that more deeply now.

It’s hard to do, partly because I’ve never really felt that I got it. The commonest Catholic argument relies on natural law theory; it makes sense to me, but it’s never seemed to make homosexuality an important enough difference to be worth forbidding. Especially considering the cost in heartache.1

A different tack is suggested by St John Paul II’s famous tome, Theology of the Body. Now, I have only read the book once and it is remarkably hard to understand—not just on account of its language, but because the ideas it discusses are difficult and subtle, and St John Paul definitely deals with them as a professional theologian and philosopher. But I will do my level best to explain what I’ve gleaned from it.2

Pro tip, Catholics: stuff that's clearly trying to say 'Church can be fun!' implies

an entirely different explanation for celibacy than the one you're trying to endorse.

A major theme of the work is that, for humanity, the body is the experience of the self as gift.3 The body is how we come into the world as independent beings: we’re conceived by bodies, carried by a body, given birth by a body, nursed by a body, all without any contribution from ourselves. And when we reach maturity, the desire to give life to new bodies is a standard part of our makeup.5 To the end, from the beginning, the body is both the gift of having a self, and the medium by which we experience every other gift—even the supernatural gifts of the sacraments.

The body is the self as gift. Angels, who don’t have bodies, presumably6 experience their selfhood differently. A naked intelligence, created directly instead of by the mediation of parenthood, would surely receive its existence as a gift, but I doubt that their experience of giving of themselves is at all analogous to ours; this may be one of the things that they desire to look into. And each angel constitutes an individual act of creation, whereas humanity is created as a web: the independence of angels from one another is complete, each individual is like a species unto itself, but the interdependence and, in the last resort, interrelatedness of all men is an unavoidable fact.

And what does all this have to do with sexuality? The contention is that, in sex, we experience one of the ways in which we’re made in the image of God. We display the power to beget: that is, to bring new life into the world, derived from our very bodies, and yet a thing distinct. The animal vehicle was prepared for this over æons of evolution, from microbe to primate, and when the divine image was imprinted on Homo to make him Sapiens, this too was taken up, given a new and unheard-of meaning. The unthinking animal that simply wants its mate was transfigured, into the ghost of a god that wants to breathe a new kind of life over the whole face of the earth.

Which means that engaging in sex in a way that excludes the possibility of giving the gift of life is a kind of refusal of creation. We aren’t obliged to have sex (which is itself a bit of a philosophical puzzle, but if I tried to examine that now this post would never end), but if we do, we can’t deliberately close ourselves to its essential meaning. Contraception, homosexuality, masturbation—even an excessive use of NFP—are ruled out, not because only bad people do them or something ridiculous like that, but because they fail to truly embrace the full significance of sex. When they are well-intentioned, they represent the same thing that Charles Williams (who was as subtle a lover as he was a theologian) described the adulterers Paolo and Francesca representing, in the opening cantos of Dante’s Comedy:

The formal sin here is the adultery of the two lovers; the poetic sin is their shrinking from the adult love demanded of them, and their refusal of the opportunity of glory. … The adultery here is only the outer mark; the sin is a sin possible to all lovers, married or unmarried, adulterous or marital. It is a sin especially dangerous to Romantics … At the Francescan moment the delay and the deceit have only begun; therefore their punishment—say, their choice—has in it all the good they chose as well as all the evil.7

The idea here is not that gay people are any less dignified or worthy of receiving and giving love4 than straight people. (There are Christians that think that; it’s shitty theology as well as a shitty attitude.) It is that sexuality has, at any rate for us humans, a specific character and purpose, and that, having received our bodies as a gift, we are obligated to use them in accord with the design of the One who gave them, whether we’re straight or gay or anything else. If we want a kind of sexual experience that doesn’t embody the full gift of self—even if it happens to be heterosexual—then yes, we have to refrain from fulfilling that want; and, if the only kind of sexual experience we want is one that doesn’t embody the full gift of self, then yeah, we’ll have to refrain entirely. And that sucks big time.4

Though we might find it comforting with regards to some people.

But is that the way it is? Ha, of course I’m not going to tell you this time.

✠ ✠ ✠

1We certainly aren’t all unhappy all the time, not even me. Some Side B gay Christians aren’t unhappy at all, and take to celibacy like ducks to water. But some of us are, and it’s over the sadness that the intellectual (and individual) difficulties arise. No amount of pointing to happy celibate people erases that.

2Helped in no small part by my spiritual director, as well as the writings of Christopher West. Some Catholics complain about West’s reading of the text, especially his accent on (and, to many, idealization of) marriage; and I don’t agree with him in every detail myself. All the same, he’s one of the most accessible commentators on TOB, and I think his contribution extremely valuable.

3The fact that this sentence can be read two ways4—gift as given to us, or gift for us to give—is deliberate.

4Phrasing.

5Sexually the desire is virtually though not quite universal, and emotionally it doesn’t seem far behind.

6Looots of speculative theology going on here. Fair warning.

7The Figure of Beatrice, pp. 118-119.

.jpg)

Thanks, always, Gabriel, for your thoughts, pathos, and didactics. I've not read Theology of the Body, but really I ought to soon, once the semester dwindles down. I remember getting into a conversation with a Catholic friend as well -in this case around the heterosexual marriage of one who knows themsel(f) to be barren. Would it be similarly sinful for a barren woman to enter a marriage knowing that her womb can produce no children -and maintain in that marriage the intimacy of that gifted body?

ReplyDeleteCatholic, and similarly, Orthodox theology, in that respect, has a much more defensible position on its stands on sexuality than Protestantism, in no small part because it sticks to its opinions on Homosexuality, abortion, and contraception *for the same reason.* But by extension, would the barren person too be included in this? Should the barren person assume that this indisposition towards bearing children imply a life of celibacy?

Again, I mean this neither as a smug rebuttal (wouldn't know what I'm rebutting), nor some sort of hypothetical masturbation (though this, I admit, I do very often online). I guess I'm coming to it from the perspective of what my friend said in reply. At one point in the conversation, we had paused down our jaunt through Chicago, and he shook his head. "But sex is more than that," he said. But he couldn't say more than that. My friend J has remained an extremely little-o orthodox Christian, and has in many ways been a great support throughout my assayed celibacy. But we had come to an impasse, particularly when most of his justification for my celibacy was the reasoning of The Theology of the Body; about the implausibility of life. In short, is sex just more than that, and can it be used and good and fulfil it's natural purpose beyond the sheer production of infants? Gosh, I'm rambling, and sounding dangerously like a Margaret Sanger, so I best silence myself here. Mere musings, friend.

Josh

I don't think you sound particularly like Margaret Sanger; but to address your question.

DeleteInfertility is, on the Catholic view, a rather different problem, because it isn't chosen by the infertile person. (I'm speaking here of infertility that comes from genetic defect or disease -- deliberate self-sterilization would, in the terms of this discussion, be the same kind of thing as contraception.) A person who wishes to be open to life, but whose body doesn't respond, is guilty of no fault; and both Scripture and subsequent tradition record miracles of fertility granted to barren women (or perhaps to barren men, since in certain cases we don't know who was the infertile one, e.g. the parents of St John the Baptist). This isn't to say that an infertile couple should expect or demand a miracle -- only to illustrate that the problem here is *fixable in principle,* as it were: it doesn't lie in the will of the person or the character of the sexual act, but on secondary factors not under the person's control.

Now, a person could be wrongly pleased with infertility, and this would be a morally unhealthy attitude. But this would only be making a vice out of necessity. The moral choice of the will is always present to us, even when the material it normally works on is not.

If we take a gay relationship into consideration, there are certainly couples who would very much like to be open to life. I've known some, mine for instance. The problem does lie precisely in *the character of the act.* Whatever we may wish it did, or would have thought or hoped it could do, gay sex *can't* share the fertility of either partner with the other, even at maximum health and functionality, even at maximum intimacy and devotion. If I may put it so, sex is more than being open to life, but it is not less; if being open to life is not merely unlikely but out of the question, so, on Catholic principles, is the act.

Parenthetically, it is also possible that God might allow barrenness as a sign that a person was called to celibacy; but I'm inclined to doubt it. I'm very confident that it will never be the *only* sign of a vocation to celibacy -- that will always require deep discernment, not a checklist of "symptoms." :)

Is the body of a gay person a gift or a taunt? Its most immediate function seems to be an occasion of sin rather than anything substantive. It's like me giving a box of chocolates to a child who's allergic to them, then telling him that he must be grateful for the gift but also not eat any. He might, say, admire the craft with which the chocolates were made; he may watch his siblings enjoy their own chocolates and derive some abstract form of vicarious pleasure from that; but he can never actually eat one.

ReplyDeleteThe child, in this case, would be completely justified in thinking I was an asshole if I did this.(1) The "gift" is not actually a gift. It's just a cruel way of throwing his disability back in his face. Why would it not be justified, then, to think that having been allowed to have one's sexuality corrupted by homosexuality does not constitute a larger, grim eschatological message about what plans God has in store for one? Then, having drawn this eminently reasonable conclusion about God, why not use the "gift" one has been given as one sees fit?

(1)The child in question would be accurate in thinking I was an asshole for any number of reasons beyond this example, but that's a subject for another comment.

If the child is in fact allergic to chocolate, then he shall be ill-advised to eat the chocolates anyway no matter how assholetastic the parent in question. However, I don't find this answer altogether satisfying, and I suspect you shan't either.

DeleteThe truth is that I don't have a good answer to this. I can point to a few mitigating factors: as that the body is for a great deal more than sexual intimacy, so that the analogy is limited in certain respects. But no mitigating factor, nor the sum of them, can erase the stark appearance of unfairness -- even (though I may be accused of melodrama), the sense of being told, "Take thine only son, Isaac, whom thou lovest ..."

Now, I do believe that this appearance of unfairness is only an appearance, because I have confidence in the goodness and wisdom of God, and in the clarity of His voice being conveyed by the Catholic Church. But I don't have any *solution* to the paradox -- only a conviction that the paradox is in principle soluble, which is a very different thing. I will not pretend to possess truths or graces of which I am bereft; it would be insulting to the suffering we endure, and even insulting to the idea of enduring it. This is one of the many reasons that, although I consider myself bound in conscience to believe and confess what the Church teaches, I can't find it in my to be severe toward anyone who doesn't.

I have made a very imperfect attempt to guess at the outline celibacy might have in the theology of the body in my next post; a post yet to come will address why I do trust God and the Church as I do, which is the linchpin of it all. But I don't claim to have any answer to this problem as such.