The lover sees the Lady as the Adam1 saw all things before they foolishly chose to experience good as evil … The phenomenal Beatrice—Beatrice as she is in this fallen world—has for an instant been identical with the real Beatrice—Beatrice as she (and all things) will be seen to be, and always to have been, when we reach the throne-room … Romantic Love is neither necessarily joined to bodily fruition nor necessarily abstracted from it: the way to which the glory invites us may run through marriage or it may not. Unless it were possible—and heavenly—to be enamoured of the glory without desiring the woman, how should we ever grow mature for the life of heaven where that glory in its fullest meridian blaze will clothe every woman and every man, every beast, blade of grass, rock? (‘In the third heaven the stones of the waste glimmer like summer stars.’)

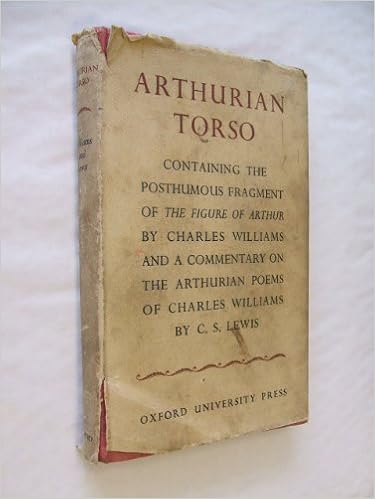

—C. S. Lewis, Arthurian Torso pp. 116-118

✠ ✠ ✠

Continuing in my analysis of Dr Feser’s paper, I have again come across a total, categorical disagreement. Let’s start with his allusion to The Four Loves:

C. S. Lewis usefully distinguishes Eros from Venus. Venus is sexual desire, which can be (even if it shouldn’t be) felt for and satisfied by any number of people. Eros is the longing associated with being in love with someone, and no one other than that one person can satisfy it. Obviously Venus can and very often does exist without Eros. Eros typically includes Venus, but it not only focuses Venus specifically on the object of romantic longing, but carries that longing to the point where Venus itself, along with everything else, might be sacrificed for the sake of the beloved if necessary. … As Lewis wisely notes, it is an error to think that Venus without Eros is per se morally suspect. … Eros is too unstable and outside our control to think it essential to the moral use of Venus. Sometimes mere affection (which, like Venus itself, can be felt for any number of people) has to suffice to civilize Venus.2

So far, so good, and a sound reminder to our culture, which is (I think) more Eros-crazed than sex-crazed, and that irrespective of Christian belief. As Lewis points out through the mouth of his devil Screwtape, the fact that we think marrying for the sake of preserving chastity and raising a family is low, as compared to marrying for love, is a symptom of how far from the idea of marriage as a sacrament we’ve really come.

But then Feser takes a turn in his argument in which I absolutely cannot accompany him.

Like Venus, Eros is natural to us. It functions to channel the potentially unruly Venus in the monogamous and constructive direction that the stability of the family requires. Of course, a respect for the moral law, fear of opprobrium, and and sensitivity to the feelings of a spouse can do this too, but unlike Eros the motivations they provide can all conflict with the agent’s own inclinations, and are thus less efficacious. … Venus and Eros, then, considered in terms of their natural function, might be best thought of not as distinct faculties, but as opposite ends of a continuum. Venus tells us that we are incomplete, moving us toward that procreative action whose natural end … requires the stability of marital union for its success. Eros focuses that desire onto a single person with whom such a union can be made and for whom the Erotic lover happily forsakes all others and is even willing to sacrifice his own happiness. Eros is the perfection of Venus; mere Venus is a deficient form of Eros. … ‘Consummate love’ … combines all three of the basic kinds of love—commitment, the intimacy of friendship, and the passion that begins with mere infatuation but develops into something more stable. It is difficult to achieve, but is commonly regarded as definitive of the best marriages.3

The Birth of Venus, Sandro Botticelli, 1486

A credible theory; but, as a student of history, a poet, and a lover,4 I firmly assert that it’s all wrong. To begin with, Eros does have a tendency—probably even a predominant tendency—to fix the lover’s desire upon a single beloved. But this tendency does little else to govern Venus, and as a rule Eros (in its ‘chemically’ pure state, without the governance of a well-formed conscience) has no interest in any moral law whatever. Among the passions, none (except maybe religious passion!) shows a stronger tendency to resemble the Unfettered archetype. So to describe its natural direction as ‘constructive’ is, in my opinion, special pleading.

Then there’s the observation that principle, shame, and decency can all serve the same purpose Dr Feser assigns to Eros, but that they may conflict with the person’s inclinations. What, and Eros can’t? My life is the very story of Eros conflicting with others of my own inclinations. And I am sure I’m not the first edition of that story. It isn’t clear to me that Eros even tends to streamline one’s motives, let alone that it was designed to do so.

Thirdly—and this is a lesser point, but it’s important, given the claims made by Neo-Scholasticism for what shows something to be natural—it must be pointed out, as a matter of historical record, that romantic love was not regarded as a dignified or spiritual phenomenon until the twelfth century, at least in Christendom and its Euro-Levantine predecessors5—except, in Greece and later in Rome, for homosexual Eros. To revere romantic love, that fanatical, self-abasing, inconstant, reckless, and involuntary phenomenon, was as ridiculous to our Christian ancestors of the early Middle Ages as it was to their pagan ancestors of the classical era. Nor, until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, was the romantic tradition linked to marriage even by Romantics; for the Troubadours who originated the tradition of courtly love, adultery was of its essence.6 The idea that Eros is shown by actual human habits to be naturally directed toward marriage is an artifact of a long and localized cultural development—or, more bluntly, pure moonshine.

In other words, the original rock stars were groupies for their fans.

As I’ve written about several times before, both in contemplating homoeroticism and in commenting on poetry, I think the basic function of Eros is something quite different, which C. S. Lewis, Dorothy Sayers, and above all Charles Williams wrote about.7 Returning to The Four Loves, it’s easy to forget the initial threefold division that he sets up, which cuts across the four: namely, the loves of need, gift, and appreciation.

Need-love cries to God from our poverty; Gift-love longs to serve, or even to suffer for, God; Appreciative love says: ‘We give thanks to thee for thy great glory.’ Need-love says of a woman, ‘I cannot live without her’; Gift-love longs to give her happiness, comfort, protection—if possible, wealth; Appreciative love gazes and holds its breath and is silent, rejoices that such a wonder should exist even if not for him, will not be wholly dejected by losing her, would rather have it so than never to have seen her at all.8

This appreciative love, Eros-as-awe if you will, is not primarily directed toward union with the beloved. It is not a way of possessing, nor even of giving, but of seeing; it is contemplative, where need-love is (usually) penitent and gift-love is active. All three have their place. But contemplative Eros will not be directed to an end other than contemplation. Lord, dost thou not care that my sister hath left me to serve alone? bid her therefore that she help me; and he would not.

Of all the loves [Dante] had known … [his love for Beatrice] is the one which, with will and judgment assenting, he declares to be a revelation of divine truth. It is not the febrile anguish of the death-Eros, in which possession forever mocks desire; nor yet the simple and affectionate exchange which does not look beyond possession. … It is a love whose joy—and therefore its fulfillment—consists in the worshipful contemplation of that which stands over and above the worshipper. True to its origins in courtly love, it finds its entire happiness in being allowed to do homage to an acknowledged superior.9

I don’t deny that Eros-as-need and Eros-as-gift exist, and of them, Dr Feser’s evaluation might possibly be accurate. But those experiences are so irrelevant—I almost said, so alien—to Eros-as-awe, they’re nearly as different from it as they are from the other loves. I’m tempted to say, oxymoronically, that need-Eros and gift-Eros aren’t even Eros.

I won’t quite go that far in fact. When defied, language has a way of avenging itself. And I’ve studied enough Greek mythology to be wary of invoking the wrath of any of the gods, let alone such potent deities as Eros and Apollo. But I will say that Eros is an essentially different thing from conjugal love, and that it’s not psychologically or morally necessary to have both for the same person, nor both at the same time—nor, indeed, to have either one at all. I think conjugal love is more a matter of storgê (governed by the virtue of justice) than of Eros necessarily.2 I therefore disagree entirely with Dr Feser’s assertion that ‘it is hard to see how marriage and family as institutions could survive unless Erotic and consummate love were generally honored … and approximated at least to some significant extent in most marriages.’ Marriage and family existed for a minimum of centuries in Euro-Levantine culture before marital Eros was honored by anybody.

But all this is actually quite consistent with a Thomistic metaphysic—consistent, if not perhaps very characteristic of its proponents. Then again, we had to wait seven hundred years between Dante and Charles Williams: philosopher-kings are plentiful and may be bought in bunches at any bookstore, but the philosopher-poet, the visionary of ‘the feeling intellect,’ the scholar of Romantic Theology, these are rare men.

This should conclude the erotic digression; my analysis of Dr Feser’s work will continue in a subsequent post.

✠ ✠ ✠

1Charles Williams (and Lewis in discussing Williams’ work) often refers to unfallen man, of both sexes, collectively as ‘the Adam.’ Since the Hebrew ’adham does simply mean ‘human,’ generically, there is a linguistic case to be made for this. Williams himself may have derived the habit from his all-important doctrine of the Coïnherence of humanity (what could inadequately be summarized as the mutual inter-animation of mankind), or from his magical training as an adept of the SRIA.

2Neo-Scholastic Essays, pp. 392-393; the famous ‘four loves’ written of by Lewis, derived from the various Greek words translated ‘love,’ are storgê, philia, erôs, and agapê, which roughly equate to familial affection, friendship, sexual love, and unconditional love.

3Ibid., pp. 393-394.

4Or at any rate, as one who has been a lover.

5I am ignorant of the romantic traditions of Indic, Oriental, Polynesian, Amerindian, and African cultures, indeed I don’t even know if there were any. I mean, I expect there were, since all men have roughly similar impulses regardless of what they do with them. But what I’m writing here, I only know to be true of the web of cultures spanning the Morocco-Iceland-Russia-Arabia region.

6I’m oversimplifying here, but not for the reason you’d probably think. Courtly love was expected to be directed to a Lady whom you weren’t married to, and who was almost certainly married to somebody else: you, the lover, were a poet, and your beloved was a noblewoman you desired to glorify. (The element of social superiority was key in the development of courtly love; fossilized aspects of it survive even now, as when a man kneels to propose.) There were two ‘schools’ of courtly love: one considered the apex of courtly love to be enjoying one’s Lady sexually; the other considered sex to be kind of beside the point (whether opposing it on moral grounds, or just artistically indifferent), because it viewed love’s true consummation as the adoration of the Lady’s person. The former school gave us poetry like The Romaunt of the Rose; the latter, poetry like The Divine Comedy.

7All three of them, Williams especially, would shake their heads and sigh if I neglected to mention here that Dante and Wordsworth were their great ancestors in this tradition of romantic theology. Milton, Donne, Blake, and just possibly Austen may belong on the list as well.

8P. 17.

9Dorothy Sayers, Introduction to the ‘Purgatorio,’ p. 43.

Frankly, it's suspect whether Eros can be essentialized as any sort of "faculty" with a "purpose" at all. The Deposit of Faith seems to have little knowledge of it as such other than recognizing that it is something that happens sometimes (as in the Song of Songs, maybe). My experiences with psychoanalysis tell me that it's just as possible, at least, to realize that this sort of romantic love results from a type of Splitting characteristic of every personality disorder involving the so called "Exciting Object."

ReplyDeleteIf there is some natural object to this "Eros" it must be the same object as every inclination spiritual and material in the world: wholeness, harmony, equilibrium.

In my experience, that "madness" or longing is seeking a type of inner wholeness, integration, or reconciliation *inside oneself*...but looking for it in maladaptive ways, or ways that make a sort of symbolic sense but then get projected onto external objects and "taken literally" as it were, to the detriment of all involved.

The opposite side of that exciting object coin...is the rejecting object, whose dyad is characterized by resentment. Our world is Eros-obsessed as you say, much more than sex-obsessed, but the shadow side of that is our disavowed aggression, which we see leaking out everywhere as well.

I definitely admit that romantic love is often an expression of the need for interior harmony, and that the beloved is loved because she or he is, in the 'language' of the unconscious, a natural glyph for something the psyche needs. However, this would primarily cover what I've described as Eros-as-need. Eros-as-awe is (in my opinion) a distinct phenomenon, one that really is 'about' its object: 'the beloved is the first preparatory form of heaven and earth,' as Williams had it; the beloved is an 'express vehicle of the Glory,' the beginnings of *understanding* the substantial majesty of God, as opposed to merely knowing (or merely accepting) that God is the source of substance and possesses majesty. If you will, insofar as God is beyond all human understanding, Eros-as-awe is one of the things that hints at what he is like, giving content to the terms that constitute the doctrines.

DeleteOf course, Eros-as-need, Eros-as-gift, and Eros-as-awe usually coexist within a single person; rarely, if ever, will any one of them (save possibly the first) be found in a 'chemically pure' state. Human beings are too messy for that. But I don't believe the quasi-mystical experience I've written of can really be reduced to an allegorical psycho-drama projected onto the world by the unconscious, not even a highly edifying allegorical psycho-drama. For contemplative Eros, there's a faint sensation of disgust (rather than enlightenment or resolution) at the idea that the beloved's majesty should be the lover's shadow cast upon her.

I had meant, in my quotation from Sayers above, to include a little more of what she said, but it seemed to be wandering a little too much so I decided not to. But this is a great place for it:

'If earthly love, as such, is but a type and an overflowing of our innate (though it may be unrecognized) desire for God, then it is inevitable that there should always be something in its nature which transcends and eludes possession. ... Our present [in 1955] distrust of "idealism" in all its forms is partly due to a very proper sense (which Dante shares) that soul and body are an integrated complex whose substance we divide at our peril. And it is exceedingly true that an idealistic love that is not firmly related to its divine archetype is fraught with dangers, since it may lead to a destructive self-worship -- a Narcissus-projection of our own ego upon the object of desire, and the extinction of all reality in fantasy. This is no new discovery. It is because he is so well aware of that very danger that Dante has placed the dream-image of the Siren at the entrance to those last three cornices [of Purgatory] where Excessive Love is purged. There is no more insidious enemy of the true Beatrice than the false Beatrice ... The two are distinguished most readily and surely by their effects -- the false image turning for ever inwards in narrowing circles of egotism; the true working for ever outwards to embrace the Creator, and all creation. ... The Beatrician vision is the beholding of the universal hierarchy in the "intellectual light" of the ecstatic moment. The Beatific Vision is the eternalizing of that moment in the contemplation of that Perfection beyond which nothing greater can be conceived for desiring.' (Introduction to the 'Purgatorio,' pp. 43-44)

Ah. See, I'm not sure I accept your distinction between the psychological and the spiritual. "Psyche" just means "Soul" after all.

ReplyDeleteSo I'm not sure why "need" and "awe" are separate to you. Surely the content of this awe you have described...is something humans need!

I'm also not sure how "Eros-as-awe" is "about" the beloved if it's "really about" Heaven (Heaven being, surely, "about" God...no?)

Indeed, my belief is that if something is "about" Heaven, then there is no really contradiction or mutual opposition here in saying that is "about" psychological wholeness...because what is "Heaven" other than that state of spiritual wholeness and transcendence which we can never fully achieve in this life but which we can, at least, "live towards."

I'm also not sure where I ever advocated "reducing" anything. I am no reductionist. However, I don't see a contrast between "quasi-mystical" and "highly edifying allegorical psycho-drama." I don't think the psychological is, for the fact of being of the symbolic order, any less Real, and is in my mind largely identical with the Spiritual.

As I've said before: "Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?" Freud did not set out to destroy love through deconstruction! Quite the opposite: "to love and to work" were what he sought to *make possible* in all sorts of people who found themselves paralyzed in that regard. And so many people are paralyzed exactly by the symbolic...

So when I read people like you writing all about lofty *ideas* of love that they won't let go of...I always have to think, "These people certainly seem to have a high opinion of their own intensity of feeling...but does that idealism actually serve to enable the concrete daily ACTS that actually constitute love? All the mundane sacrifice that it requires?"

In my experience, the people who make a cult of the "contemplative romantic" like this are generally exactly the people caught up in a solipsism, a "being in love with being in love" as it has been described, that so greatly subverts and frustrates achieving *ACTUAL* functional intimacy and relationship for them...(sorry, just sayin'...)

It's like Chesterton or Newman (I forget...) said about humanitarianism, no? So many humanitarians love "humanity" but don't know the first thing about loving any particular humans. And so many romantics love the idea of being in love, but seem to be pretty terrible at actually establishing any real successful human love relationship. (Personally, the character who always draws my interest and pathos and imagination most in the whole "Dante/Beatrice" melodrama...is neither of them, but rather Gemma di Manetto Donati!)

As for that disgust...well, of course the nature of various defensive and/or reparative mechanisms to vehemently deny that that's what they are. That's why the whole "cure" of psychoanalysis is bringing such facts to consciousness. Because the very fact of realizing what a mechanism is trying to accomplish symbolically...usually goes a long way towards actually accomplishing it in reality.

See, I insist pretty firmly on a distinction between the psychological and the spiritual. 'Psyche' does of course mean "soul," but then, 'psyche' and 'pneuma,' "spirit," are distinguished in Greek, and not infrequently in theology (e.g. Hebrews 4.12). The distinction I would draw between soul and spirit is (roughly) that the former is oriented toward natural ends and the latter toward supernatural ends; the former directs us to temporal and earthly happiness, while the latter directs us to eternal and transcendental happiness. Of course the two work together -- I do think they're distinct, but they aren't divided, still less opposed, except insofar as the Fall interferes with our natures.

DeleteAnd accordingly, yes, awe is something we need. But I'm following Lewis' distinction between need-love and appreciative love quite specifically and closely here. And for that matter, insofar as the different kinds of eros are distinguished, neither erotic love in general nor eros-as-awe specifically are *needs* of the human soul. Some people never experience them and are none the worse for it; and of course some who do are none the better on that account.

As to how eros can be about the beloved if it is about heaven, and therefore God -- art thou a master of Israel, and knowest not these things? God is known in His creatures ("no man hath seen the Father at any time"); all His creatures derive their being from Him and exist in Him, and each strives towards its own heavenly identity, that is, the character and purpose for which He made it; sin is, among other things, the refusal of the creature to be united to its heavenly identity.

Forgive the pontifical tone. What I ought to say is, these are the views I hold, and upon which my theology of romantic love (with many other things) is based.

I doubt this is what you meant, but your explanation of heaven makes it sound like you think of it as a state of mind. I revolt utterly against any such idea. As Lewis says in another place, "Do not blaspheme. Hell's a state of mind -- ye never spoke a truer word. And every state of mind, shut up within itself, is, in the end, hell. But heaven, that's reality itself." To be sure, that reality *involves* spiritual wholeness and integration, if we are to enjoy it or perhaps even be aware of it. But it is most emphatically not contained within ourselves. We are contained within it.

It is for this reason that I spoke of love being *reduced* to allegory. Need-love may desire the beloved for her effects upon the lover, but there is nothing appreciative love is less interested in. And the idea of the beloved being merely a glyph of himself is boring, sad, and horrifying: it destroys the authenticity of the beauty; it makes the glory an illusion, and a self-incestuous one.

None of this is to say that things that happen in one's head aren't real or aren't important. Allegory can be a magnificent genre -- Dante being an outstanding example of the fact, along with de Lorris, Spenser, Bunyan, Tennyson, and Williams, to say nothing of the uses it's put to in Scripture. But it *is* to say that things-happening-in-your-head doesn't at all satisfy the thirst of the contemplative lover. Interior health is one dimension of reality; but the Glory comes from without, and that (insofar as he is healthy) is what he sees and desires. You say that Freud sought to make love possible to people who were inhibited; a noble goal, but speaking for myself, if I accepted that romantic love were *only ever* a projection of my own needs, I couldn't possibly find it worthwhile or interesting. And that, to me, is an intensely depressing and ugly idea. As our master Chesterton put it (talking about something else), it explains everything, in a way that makes everything not seem worth explaining.

About being in love with being in love, yes, it's a real danger. Dante and Williams were peculiarly alive to it, as was Sayers, which is one reason I included the quote from her above. That is why romanticism requires intelligence, as well as passion, if it is going to be used as a Way of the soul. One of the notes that Williams strikes over and over, in his prose and poetry alike, is the need for precision, accuracy, exactitude, attention. Mere luxuries of emotion will not do. But that abuse of the Way does not prove romanticism a fraud, any more than using religion to flatter one's ego proves monasticism a fraud. Nor are all romantics as childish as you seem (*seem*) to imply; Williams and his wife had a famously happy marriage, no doubt in part because of the intelligence with which he pursued the Romantic Way.

DeleteI gather from your seventh and eighth paragraphs that you're hinting that my erotic heartache is, for lack of a better way of putting it, my own fault, due to idealizing my feelings? If so, then, talking of precision, I'd prefer it to be said plainly. There's only so much I can defend myself against any such charge, since -- in the only romantic relationship I've yet had -- I did hurt myself and my partner very badly by my lack of self-control. However, I will defend myself to the extent of pointing out that, if we speak of sacrifice, I sacrificed the only earthly happiness I've yet known for the well-being of the man I loved, and it was precisely romantic love that prompted me to do so. I loved him, I knew very well that if I loved him I had to put my money where my mouth was, and so I did. And while idealism (the frame of mind) doesn't really prepare a person to do anything, pursuing an ideal was exactly what made me able to make that sacrifice.

Given that it ended, perhaps that does not in your view count as a "real successful human love relationship". And, no, I haven't had a boyfriend since then (so, for a little over four years), though that's partly due to spending some years trying to be celibate. However, I'm trying here to argue for the legitimacy of the Romantic Way, not that I'm a good example of it; psychoanalyzing me for the origins of that opinion, however entertaining, is neither here nor there, until and unless you already know on other grounds whether it's true.

Regarding the disgust -- well, if both repulsion and attraction are to be taken as signs that your point of view is correct, then I confess I'm rather put out, since it makes any analytical discussion of emotions rather difficult. If it makes any difference, I would point out that I said the disgust was faint, not vehement, and bothered to mention that it was faint partly because I half-expected that it would be cited as a sign of a self-defense mechanism. But if it can be fitted equally well into both our hypotheses, perhaps it would be better to ignore it, since it can't really serve as evidence for either one against the other.

Whether my general conduct displays the mundane sacrifice that love requires is not mine to say. You would have to ask people who know me. But if -- and of course I may be misreading you; if so, please correct me -- you are indeed hinting that I'm affectively immature, in love with being in love, and warped and stunted in my capacity for intimacy, all thanks to my idealization eros: then I shall say I don't much care for being psychoanalyzed by strangers, and that if I did I would prefer it at least to be done in the privacy of e-mail, if only as a symbolic concession to the guidelines of the therapist's profession.