+ + +

This is the place of what is probably the most famous episode in the whole Commedia, the episode of Paolo and Francesca -- which is always quoted as an example of Dante's tenderness. So, no doubt, it is, but it is not here for that reason ... [I]t presents the first tender, passionate, and half-excusable consent of the soul to sin.

Up to this point (Inf. V) the Imagination has been in suspense; it has not chosen -- whether from a shameful shrinking choice into spiritual cosiness, or from its not being confronted with this religious choice. It is now shown as choosing, and the choice is made as plausible as it could possibly be. ... What indeed was the sin? It was a forbidden love? yes, but Dante (in the place he gives it in the Commedia) does not leave it at that. He so manages the very description, he so heightens the excuse, that the excuse reveals itself as precisely the sin. ... [I]t is lussuria, luxury, indulgence, self-yielding, which is the sin, and the opening out of hell. The persistent parleying with the occasion of sin, the sweet prolonged laziness of love, is the first surrender of the soul to hell -- small but certain. The formal sin here is the adultery of the two lovers; the poetic sin is their shrinking from the adult love demanded of them, and their refusal of the opportunity of glory. Hell, in Dante, is in the shape of a funnel, and a funnel is exactly what hell is; and this moment of the lovers' yielding is the imagination swept around the inner edge of the funnel.

-- Charles Williams, The Figure of Beatrice, pp. 117-118

+ + +

The article "From Youth Minister to Felon," recently published and thereafter retracted at Christianity Today, inspired a considerable amount of backlash. It was an account, intended by its author to serve as an example and a warning of how easy it is to slide into sexual sin in a ministerial position, of the author's own illicit sexual relationship with an underage girl in his youth group. It has been extensively criticized as being narcissistic, presenting justifications and excuses for his conduct, minimizing the predatory nature of the relationship, ignoring the consequences for the victim, and implying that she shares in the responsibility and blame for what happened. In addition to Twitter hashtags such as #TakeDownThatPost (a protest against the article itself) and #HowOldWereYou (in which victims of abuse shared parts of their own stories), some articles have been written in reply -- notably "To Publish a Predator" and "It's Abuse, Not an Affair," both also hosted by Christianity Today.

I was a victim of multiple rapes myself, beginning when I was thirteen, as I've dealt with hitherto. The man who raped me was not in the church's employ in any way, or an important figure in the congregation; he was, however, suffered to depart quietly after a private confrontation with the clergy (or so I understand), and so far as I know has never been brought to trial. Nor do I believe for one moment that I am the only young person he molested.

The tortuous slowness with which Christians are coming to face the reality of sexual predation within our congregations is horrifying; probably almost the only reason that the Catholic Church is doing as well as it is, is that it has been forced to, by the ghastly revelations of a decade ago. Meanwhile, every few months or so, I hear some new story of abuse, often at the hands of church leaders, sounding like something out of a nightmare. But the problem is beginning to be recognized, and in some degree dealt with. Above all, the wicked culture of silence on the subject is being dispelled.

The lashing out against this man's article bothered me, though. Now, it must be admitted, the article is seriously defective in certain ways: it does concentrate primarily upon the consequences in the abuser's own life, for one thing. But I'd like to parse some of the criticisms a bit.

For instance, both of the replies I linked to above refer to the abuser as a predator, one of them comparing him to Humbert Humbert, the pedophilic and unreliable narrator from Lolita. That's possible. But it seems to me to represent a dangerous and undesirable tendency to conflate every kind and degree of rape with every other; which is not a defense of rape, any more than distinguishing between first and third degree murders is a defense of third degree murder, but it is an assertion that distinctions are good for clear thinking while conflations are not. I'm reluctant to call this man a predator, not because what he did was okay, but because what I see in reading it is -- a man who hasn't fully come to terms with the gravity of his sin? very possibly, but, that aside -- a man who did indeed, as he describes, slide into sin slowly and by degrees.

And that distinction does matter. Not because it makes statutory rape okay; of course it doesn't. But it does, for example, make the difference between a good man corrupted by his desires and a man who pretended to be good to make his evil more effective. And that difference is important, primarily because different responses are needed, in both cure and prevention, for differing situations. To treat every case of this wrong (or any wrong) as though it were the worst of its kind actually makes things worse, not better; because a response that suits the worst case probably isn't suited to correct the problems of milder, or at any rate different, cases. Which leaves these other cases effectively untreated. And that means that the problem persists.

There are other things about the response to his article that bother me, too -- as that people read him to be making excuses when he spoke of feeling unrewarded at home, for instance, when I read that rather as him confessing one of his own interior lies. But I'd like to turn from this specific instance of the conversation about rape culture to the conversation as a whole.

I am flabbergasted that anti-rape activism should even be necessary: I was raised with the belief that rape is the worst sexual sin (and crime) possible; and I feel confirmed in that belief by St. John Paul II's Theology of the Body, for, insofar as the body is fundamentally a gift, the forcible taking of that gift -- whether by violence or otherwise -- is the deepest perversion of it possible. Nonetheless, there are three elements of the conversation about rape, coming from the anti-rape activist side (or such is my impression), that seriously bother me.

1. The phrase "rape culture." I don't necessarily object to this phrase in and of itself. What I do object to is people tossing around buzzwords, especially about something as grave as this subject, without bothering to explain them -- whether to themselves or their audience. I complain of this phrase because, in the last two or three years (which is as long as I happen to have seen it around), I've seen it actually explained exactly one time, and I've seen tons of unrelated or even incompatible things all described as being part of "rape culture," from making jokes about rape to, you know, actually raping people. That kind of vagueness isn't okay. No evil justifies substituting rhetoric for thought. Not knowing what you're talking about makes harder to address evils, not easier, and riling people up is not the same thing as actually dealing with a problem.

Now, far be it from me to say that everybody who uses this phrase is behaving as a mindless rabble-rouser in so doing -- of course that isn't true. Nor am I saying that rape culture is not a problem: insofar as I don't know for certain of an agreed-upon definition, I couldn't do so if I wanted to; and I certainly recognize rampant problems surrounding rape, like victim-blaming (whether the person doing the blaming is the rapist, or others, or the very victim), which I assume are at least part of what the phrase means. But I am in nearly as good a position as anyone* to understand the evil being dealt with, and I'd like to see it dealt with intelligently. That requires clarity, and clarity is something I don't feel I'm seeing in this discussion. (Of course, that may be very largely because both I and the other conversants that I'm familiar with are from the internet; but, although that explains, it does not excuse, sloppy thinking and sloppy speech.)

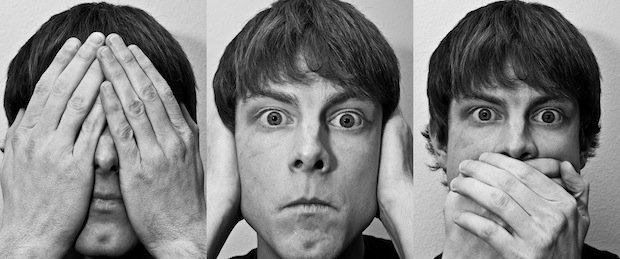

Your most powerful natural weapon against evil isn't anger. It's this.

2. The dehumanization of rapists. It may sound strange to object to this -- not least because being raped is a dehumanizing experience. But one injustice is not solved by an opposite injustice. If we object to dehumanizing people, simply as such, then we ought to object to criminals being dehumanized; whereas, if we don't object to dehumanization in itself, then one of our reasons for objecting to rape is clean gone. I prefer to maintain that dehumanizing people is always wrong, even if they're awful.

If you don't know what I mean about the dehumanization of rapists, read a few articles on the subject. Note the language and the tone: the way words like "predator" and "monster" are used, the tendency to imply (or state outright) that no punishment is too bad for them, the way in which everything that would connect them to our own humanity is denied. This is perfectly understandable -- I mean, most people aren't rapists. But I believe that it is a fundamental error, from two perspectives.

First, there is the risk to our own consciences. Whenever we set ourselves above a particular class of sinners -- however accurately, however justly, however even necessarily -- there is always a tug to treat them as less human than ourselves, for how else could they have done something so hideous? But unless they were psychologically sick, they sinned because they gave in to a temptation. And the thing about temptation is that it doesn't manifest itself, not usually, as the Weird Sisters prophesying upon a blasted heath or anything like that: it starts off, so often, as something small and harmless and almost innocent.

This was one of the essential points of the anonymous pastor-turned-criminal's article. He may not have been the right person to make the point. Or it may not have been decent for him to make it so soon after the events in question. But it is a point we ought to take to heart regardless of its source. I have to wonder whether a small part of the reason that the article inspired such a forceful response is that, in his gradual edging into this horrible evil, we recognized a pattern we are familiar with in our own lives, and resented the reminder.

No one describes this better than C. S. Lewis, commenting on Milton's depiction of Eve in Paradise Lost, just after the breaking of the primeval covenant. After a short account of the first few, pathetic and squalid, movements of Eve's fall, he writes:

But presently she remembers that the fruit may, after all, be deadly. She decides that if she is to die, Adam must die with her; it is intolerable that he should be happy, and happy (who knows?) with another woman when she is gone. I am not sure that critics always notice the precise sin which Eve is now committing, yet there is no mystery about it. Its name in English is Murder. ... If the precise movement of Eve's mind at this point is not always noticed, that is because Milton's truth to nature is here almost too great, and the reader is involved in the same illusion as Eve herself. ... Thus, and not otherwise, does the mind turn to embrace evil. No man, perhaps, ever at first described to himself the act he was about to do as Murder, or Adultery, or Fraud, or Treachery, or Perversion; and when he hears it so described by other men he is (in a way) sincerely shocked and surprised. Those others 'don't understand'. -- A Preface to 'Paradise Lost,' pp. 125-126

Every little step that this man described rings true. The small beginnings, the little omissions, the edging ever closer. Rape isn't the only crime, still less the only sin, to which that applies.

The second problem with dehumanizing rapists is that it cuts them off from the possibility of healing. I can understand someone whose response to this is that they don't deserve to be healed; but, from a quite utilitarian and even quite selfish perspective, I would far rather rapists stop being rapists than go on as they are.

It may well be that for some, whose crimes were motivated by a sociopathic inability to empathize with others, no healing is possible except by a direct miracle. But for others, healing of the soul is possible: excruciatingly painful, like trying to unmake a Horcrux, but possible. And for these men and women, who have, in however damaged a form, a conscience -- well, Brandish your ropes and your boards and your basket-hilt swords, but what is there can punish like a conscience ignored? They have to wake up every day and look in the mirror, knowing what they've done. (Small wonder that this ex-pastor did not address the consequences for the girl he abused; it may well be that he simply can't bear to contemplate them -- a bad and inadequate reason, but pitiable.) How on earth are they to recover if they are told by everyone around them that they are subhuman monstrosities? For if they are told that, and believe it, all motivation to resist their darker impulses is gone. It is only if a better self is really available to them that they will have any hope, and, with that, any reason left to fight.**

The third thing that bothers me about the conversation about rape culture remains.

+ + +

Everyone says forgiveness is a lovely idea, until they have something to forgive, as we had during the war. And then, to mention the subject at all is to be greeted with howls of anger. It is not that people think this too high and difficult a virtue: it is that they think it hateful and contemptible. 'That sort of talk makes me sick,' they say. And half of you already want to ask me, 'I wonder how you'd feel about forgiving the Gestapo if you were a Pole or a Jew?'

So do I. I wonder very much. Just as when Christianity tells me I must not deny my religion even to save myself from death by torture, I wonder very much what I should do when it came to the point. I am not trying to tell you in this book what I could do -- I can do precious little -- I am telling you what Christianity is. I did not invent it. And there, right in the middle of it, I find 'Forgive us our sins as we forgive those that sin against us.' There is no slightest suggestion that we are offered forgiveness on any other terms. It is made perfectly clear that if we do not forgive we shall not be forgiven. There are no two ways about it.

-- C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, Book III, ch. 7

+ + +

3. The more I read in the conversation about rape, the more I see every mind turning to revenge as a solution -- revenge, and not forgiveness.

It comes in a thousand forms. And it doesn't, not yet, actually call itself revenge; in a society like ours, that still has vestiges of an originally Christian compassion as basic assumptions of conduct, it calls itself self-esteem, or justice, or having no obligation to let toxic people into your life. And the reply to any mention of mercy and pity doesn't call itself unforgiveness, either: it seldom calls itself anything at all, but instead, as C. S. Lewis saw, vilifies the idea of mercy and pity as a contemptible and weak refusal to recognize evil for what it is.

Now, from the World (i.e. as the opposite of the Church), this is to be expected. Forgiveness -- as distinguished from revenge on the one hand, and mere bland acceptance of evil on the other -- is truly supernatural. But this is something I see more and more from Christians, I feel, and that disturbs me. People say that you cannot oblige or force someone to forgive, and you can't: except in the sense that Christ does, by telling us that that is what it means to be a Christian at all.

Saint Maria Goretti appearing to Alessandro Serenelli in a dream, giving him lilies that burned his hands.

It is (I believe) lawful, and indeed necessary, to take as long as you need to to forgive; to grieve the wrong you have suffered; to rebuild yourself, including your sense of self-respect. To work toward forgiveness while you're not yet able to effectively do it, is no different from any other duty in the Christian life. And cases like this do neatly illustrate the distinction that theology calls the difference between absolution and indulgence: to forgive a rapist, or any other sinner whose sins are rightly criminal, is not the same thing as letting them off being punished. Forgiveness, absolution, means choosing to love the offender, choosing to will what is best for them, laying down bitterness and spite and the whole complex of desires that can be summed up in the single desire to hit back. Indulgence means letting them off the consequences, which may or may not be good for the offender.*** What is best for them will, usually, mean that they be punished, with the hope that the punishment will serve as a corrective; and what is best for them doesn't necessarily mean establishing, or re-establishing, an intimate friendship.

Although, it bears saying, it could. After all, that is exactly and without hyperbole what Jesus does, every single time we come to Him and ask Him to forgive us for sinning against Him, in any way. For the children of this age not to forgive is the most natural thing in the world; for the children of the age to come not to forgive, is a hypocrisy of which we were warned in one of the Lord's most frightening parables.

It took me years to forgive the man who raped me; I had to learn that it was not my fault, I had to get through the anger and the nausea that live in those memories. I still feel disgust when I think of him -- along with a great deal of pity for his twisted soul. To forgive does not mean pretending that there was no evil committed, or that the evil isn't important and horrible. It just means forgiving it.

Pause for a moment and consider the example of our own most ancient leaders, the Apostles.

And he sent messengers ahead of him, who went and entered a village of the Samaritans, to make preparations for him. But the people did not receive him, because his face was set toward Jerusalem. And when his disciples James and John saw it, they said, "Lord, do you want us to tell fire to come down from heaven and consume them?" But he turned and rebuked them. -- Luke 9.52-55So Jesus is on His way to Jerusalem, and a village of Samaritans will not receive Him because He is sticking to the specifically Jewish practice rather than keeping the Passover with them. Naturally, the Zebedee brothers -- and here perhaps we see why they were nicknamed the Sons of Thunder -- say to Jesus, "Alright, Lord, would You like us to murder this entire village, for You?"

But surely, surely, that's a fluke -- the Apostles weren't just going around murdering people for kicks or anything, I mean, none of the others ever approved of that kind of --

And as they were stoning Stephen, he called out, "Lord Jesus, receive my spirit." And falling to his knees he cried out with a loud voice, "Lord, do not hold this sin against them." And when he had said this, he fell asleep. And Saul approved of his execution. And there arose on that day a great persecution against the church in Jerusalem, and they were all scattered throughout the regions of Judea and Samaria, except the apostles. Devout men buried Stephen and made great lamentation over him. But Saul was ravaging the church, and entering house after house, he dragged off men and women and committed them to prison. ... Saul, still breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the Lord, went to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues in Damascus, so that if he found any belonging to the Way, men or women, he might bring them bound to Jerusalem. -- Acts 7.59-8.3, 9.1-2Oh.

"This is going to be really ironic in a few years, Saul!" -- St. Stephen Protomartyr (probably)

In the case of Saint James and Saint John, it was before the descent of the Holy Ghost, who plainly revolutionized their own values; in the case of Saint Paul, it was before he was a believer at all. But the God we worship chose these men before any of that had happened, to be His own special emissaries. Our embarrassment at their sins does not appear to be shared by Heaven; nor, it must be said, by the Apostles themselves, who were responsible for recording the Scriptures that so carefully enumerate their own faults.

This is what our Lord Jesus came to do. This is what it means to follow Him. It is our special business as Christians, who bear His own name in our hearts and on our lips and foreheads, to lay down every trace of hatred, enmity and revengefulness, and to return instead, by the supernatural power of the Spirit, eternal and inexhaustible love.

+ + +

For the love of Christ controls us, because we have concluded this: that one has died for all, therefore all have died; and he died for all, that those who live might no longer live for themselves but for him who for their sake died and was raised. From now on, therefore, we regard no one according to the flesh. Even though we once regarded Christ according to the flesh, we regard him thus no longer. Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come. All this is from God, who through Christ reconciled us to himself and gave us the ministry of reconciliation.

-- II Corinthians 5.14-17

*I say nearly as good as anyone because, though I am a survivor of multiple rapes, there are two things that set me apart from many victims: first, I'm male; and second, the rapes I suffered weren't violent. They were violations, certainly -- of my human dignity, of God's design for sexuality -- but they didn't involve force or threats. As a result, I don't know how far I can adequately empathize with the female perspective of the matter, and won't deliver my own perspective as though it were universal; and, not having experienced the traumas of violence that many rape victims do, I'm reluctant to rank my own sufferings with theirs.

**I feel I am beginning to see progress on this problem in the specific sphere of pedophilia. For some years now, I've been deeply worried about the way pedophiles are treated in our culture: not, of course, that pedophilia is not horrible, but that those who suffer from such desires and want to resist them must surely feel that they have nowhere safe to turn and no one who can help them -- after all, who would? More recently, I've seen articles like this one that suggest a growth of compassion, or at least of the possibility of compassion.

***This is why the Catholic Church attaches indulgences to specific acts: an indulgence is a release from the temporal consequences, the corrective punishment, of a sin that is already forgiven; and since the corrective for the soul is still necessary (as we see in examples like this), the indulgenced act serves as a substitute for the punishment, to make sure you don't miss out on the good that would otherwise be done to your soul by a loving punishment. This is also part of why we usually get partial rather than plenary indulgences.

This post breaks me, and makes me ache. I wish I could say that forgiveness makes so much sense to me, but often it doesn't, and I am very bad at it. But what you say is true of our calling as Christians. I am challenged and inspired by Jesus. Thanks, lil Brudder. You're gonna be a quarterback when you grow up.

ReplyDeleteI dunno about quarterback, seester. But I am gonna run for two thousand yards. *hug*

DeleteGood work, dude.

ReplyDeleteThanks mang.

DeleteI like to take this approach to difficult topics, too: taking a side, but also pointing out the flaws in the most popular arguments. It bothers me greatly when Christians speak of revenge because it is so contrary to what it means to be a Christian, and I agree with you completely about dehumanization. Jen Fulwiler wrote a great section about that in her book.

ReplyDeleteI also think that, if we truly believe God is forgiving, he can forgive even people who commit terrible acts such as this man did. If God can forgive, we should at least try to do the same.

This just shows, especially the Saul/St. Paul example, that Christianity is a religion of murderers and "sinners". What with King David being a murderer and composing the psalms, which Christians pray and examples like this of pastors raping children, I am surprised that anyone even regards Christianity favorably anymore nowadays. Jesus himself may have been a righteous man, but he could have also been the greatest con artist and the first person documented with a Messiah complex. Why do you even put up with Christianity anymore? Don't you see all of the skeletons and cobwebs?

ReplyDeleteCertainly I see them, M. I don't know how well you know the history of Christianity -- perhaps quite well indeed -- but I know it well enough to be closely acquainted with some of its ugliest contents: witchcraft trials, ecclesiastical intrigues and corruption, the Inquisition. My faith is not now, and so far as I recollect never has been, based on the illusion that Christians are generally good people.

DeleteTo answer your question of why I put up Christianity (or, in my own words, why I believe it) could be answered in a book or in a sentence. The sentence is that I believe it because I think it's true, based on my analysis of the evidence, philosophical and historical, available to me. The book would be an explanation of that evidence and why I find it persuasive; for which of course there isn't space here, but I can give a precis of the more relevant factors.

You mention Jesus, and the possibility that He was insane. That is certainly a very good explanation for most people who believe themselves to be God and/or a messiah of some kind. And any account of the Church, whether that account concludes that she is the Body of Christ or a cobwebbed skeleton, can only be based upon Him. The explanation that He was insane simply doesn't satisfy me, because the only records we have of Him are too shrewd and, in fact, too funny (within His genre of repartee) for a lunatic to have pulled off, in my opinion. Moreover, His moral teaching is too complex and subtle for me to ascribe it to lunacy, which tends, when it does take a moral cast, to be monomaniacal. And the fact that the people whom He convinced were mostly peasants, who tend to be hard-headed, as opposed to religious fanatics or academics (notoriously credulous types), makes the insanity explanation difficult to maintain as well.

Since I can't bring myself (on grounds I'll leave aside for brevity) to believe that He was a liar, either, I am therefore left with the conclusion that He was telling the simple, if shockingly weird, truth throughout. And that is the fundamental premise of Christianity, Catholic or otherwise.

Turning to your remarks on Christian sinfulness and indeed criminality, it can scarcely be denied. A waggish reply would be that it proves one Christian doctrine -- that of Original Sin -- rather neatly, and in a sense that's true, but it hardly serves as a complete answer.

DeleteA fuller reply would involve pointing out that none of these things, now or in the past, have required Christianity in order to exist. Murder, rape, &c., go on quite energetically in civilizations that have never heard of Christianity, and at the hands of persons who do not profess it. Every worldview, Christian or non-Christian or pre-Christian or anti-Christian, must begin with the data of the world as we know it, and that world includes evil.

That these evils also emerge in largely or partly Christianized societies and even among Christian leaders is certainly horrible and shameful. But it must be admitted that it does square with the Christian belief that all men are sinners, that Holy Orders confer authority rather than virtue or superiority, and that the will remains as free to reject God after Baptism as it was before.

Now, none of this is a reason to accept the Christian faith, still less the Catholic faith specifically. I think it a rebuttal to certain objections to that faith, but that's different.

However, I would point to the examples of the saints as a reason to reconsider. When the Nicene Creed states that the Church is holy, this means a few things, and the belief that Christians in general will always be morally outstanding people isn't one of them. But it does mean that the Church will always be productive of saints: i.e., those rare and remarkable individuals who are not simply outstanding in virtue, but whose love and holiness shine with an unwonted and unnatural light, people whose lives are inexplicable except in terms of the personal influence of the Christ they worship. Mother Teresa, who poured out her life for decades for the poor, is of course an example; Stephen Protomartyr and Maria Goretti, whom I mentioned in this post, are classic examples of martyrdom and forgiveness for the men who murdered them; Francis of Assisi, who combined in exhaustible joy with utter poverty and charity (ministry to lepers, for instance), is one of the most enduring examples.

Again, none of this is conclusive. But I find it suggestive. I don't believe that there is any knock-down drag-out argument for Christianity, but I personally find that all of the arguments do not force belief, yet point in the same direction. That puts me in a position of asking, "Do I trust that Christ is who He claimed to be, and, correspondingly, did what He claimed to do?" And to that question, I answer "Yes."

"Why do you even put up with Christianity anymore? Don't you see all of the skeletons and cobwebs?"

DeleteI put up with Christianity because Christianity is true. The arguments for its truth are not in any way compromised by the sins you point out.

As the great Pontius Pilate once said (in perhaps the most intellectually rigorous statement in the entire New Testament): "What is 'truth'?"

DeleteThe liturgy speaks to each person separately . How serendipitous that today should be the feast day of St. Aloysius Gozaga S.J. in the traditional Roman calendar, the saint of angelic purity.

ReplyDeleteHow is it rape if you are not threatened or forced?

ReplyDeleteA good question. If we define rape as necessarily involving violence or the immediate threat of violence -- which is, rightly or wrongly, the mental image most of us have of rape -- then of course this way of talking seems nonsensical.

DeleteHowever, the law, in my opinion rightly, regards as rape all non-consensual sex -- which means that those who are not in a position to give informed and free consent (like children), and those whose consent is obtained through manipulation or deception (e.g. impersonating someone for sex -- for instance, creating a false identity on a dating website and using that false identity to seduce someone) are also treated by the law as victims of rape. I personally think this is appropriate, though, it must be said, violent rape is most certainly the wickedest kind, and doubtless has the worst effect upon the victim.

It could be argued that cases in which consent is not really possible (minors, the mentally disabled or ill) and cases of rape by fraud ought not to be defined as rape. I don't agree with such objections; but I don't think the position a monstrous one, provided that it does recognize them as not only wrong but as sexual crimes -- i.e., that they are and ought to be punishable by law. (Whether that law is administered by the state, as in our current setup, or by some other means, as in the anarchist ideals that I espouse, is for these purposes irrelevant).

Gabriel, I had no idea that anything like that had ever happened to you. It absolutely breaks my heart to hear it.

ReplyDeleteYour faith and understanding of it overwhelms me at times. I'm glad you can forgive. And I'm glad that I know you. You never fail to teach me a thing or two. :)

A great article but I just chimed in to say the award for best use of a mewithoutYou lyric goes to you, good sir (pardon my ignorance of they pinched it from somewhere else). Bravo. Robert.

ReplyDelete